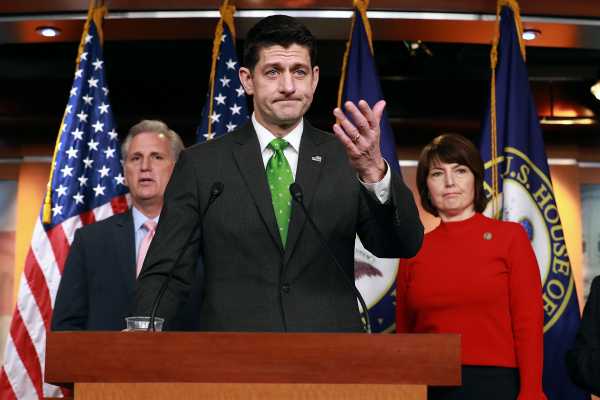

The House of Representatives is finally voting on immigration this week. It’s the result of a deal between House Speaker Paul Ryan and a group of moderate Republicans concerned about the fate of the immigrants facing the loss of their protections from deportation under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

The plan is to vote on two bills: a conservative bill written by House Judiciary Committee chair Bob Goodlatte (R-VA), and a “compromise” crafted by White House staffers, Republican leadership, and moderates last week.

But it’s hard to make a deal around Donald Trump.

Instead of spending Friday whipping up support for the compromise among wary conservatives, Republican leadership spent the day on hold, waiting to figure out if President Trump meant what he’d said Friday morning on Fox & Friends: that he “definitely wouldn’t sign” the compromise bill his White House staff had helped write.

Ultimately, a White House spokesperson told the press (and Congress) that Trump was simply confused, and that he’d sign either bill the House is taking up this week if it came to his desk. But the drama illustrated just how narrow the path to passage is for the compromise bill and how desperately it depends on President Trump’s words and whims.

There’s very little in either bill for Democrats. Both bills allow immigrants currently facing the loss of their protections under the DACA program (which the Trump administration is currently fighting in court to end) to apply for legal status in the US. The compromise bill would allow many of them to ultimately apply for green cards, making them eligible for citizenship.

But both bills make cuts to legal immigration (by eliminating the diversity visa lottery and some forms of family-based immigration), which Democrats have said is a nonstarter. And both would significantly tighten asylum standards and make it much easier for the government to detain and deport asylum seekers — something Democrats are much less willing to get on board with as the Trump administration’s separation of families at the border remains the top news story.

And while Republican leadership claimed that their “compromise” bill would prevent family separation, it really doesn’t do that at all.

So the question is whether Republicans can pass either bill on their own — and what happens if, as appears more likely than not right now, they don’t.

The “compromise” bill: citizenship for some DACA recipients, offset by restrictions on family immigration and asylum

The Border Security and Immigration Reform Act of 2018 is a sweeping and complex bill dropped just a week before it comes up for a floor vote. That makes it hard to summarize — and even harder to predict how broad its support will be. Here are the highlights:

Legalization for DACA recipients and immigrants eligible for DACA. The “compromise” bill creates a form of legal status, called “conditional nonimmigrant” status, that can be renewed after six years. The requirements for this status are largely the same as the original requirements for DACA: Applicants have to have been in the US since 2007 and have to have been under 31 as of June 15, 2012. So immigrants who would have been eligible for DACA will be able to apply even if they never actually applied or if their DACA status expired. (There are slightly stricter requirements than DACA when it comes to criminal history and expected income.)

Green cards for some legalized immigrants (and children of legal immigrants) — based on a points system. Republican sponsors of this bill claim that it doesn’t provide a “path to citizenship” for DACA recipients. But it kind of does. The bill allows them to apply for green cards, which make someone eligible for citizenship (after three or five years).

However, immigrants won’t be guaranteed to actually get green cards. They’ll be sorted based on a points system — getting more points for doing well on English-language tests, having advanced degrees, and for length of employment. And they’ll be competing for those green cards against the children of legal immigrants who are now too old to get green cards when their parents do.

It’s genuinely not clear from the House bill how many current unauthorized immigrants, with or without DACA, will ultimately get green cards through this route. But they’d probably also be able to get green cards by other means that are available to legal immigrants, like marrying a US citizen.

Shifts, and eventual cuts, to legal immigration. The bill would end the immigration of adult children and siblings of US citizens — including people who have been waiting for several years for their applications to be processed under current visa restrictions. It would also eliminate the diversity visa for immigrants from countries that don’t typically send many people to the US.

Some of these slots would be used for employment-based green cards instead, and some would temporarily go into the pool for the “points system” mentioned above, but ultimately, the bill would slightly decrease legal immigration to the US.

An asylum crackdown. The bill’s sponsors initially, and falsely, claimed their bill would prevent the government from separating families at the border. But the bill actually goes in the other direction, cracking down on families and other asylum seekers.

It raises the bar for being allowed to pursue an asylum claim in the US; unilaterally allows the US to send asylum seekers back to Mexico if they traveled through there (something that is usually negotiated with the other country in question); and allows Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to detain children and parents indefinitely.

A promise of $25 billion for the wall. Congress isn’t actually appropriating $25 billion now. It’s just committing a future Congress to do it — and halting legalized immigrants from applying for green cards if Congress hasn’t done it yet.

The conservative alternative: no chance for citizenship for legalized immigrants, deeper cuts to legal immigration

The Securing America’s Future Act was introduced in January, back when it looked like both chambers would have a serious debate over immigration reform. It went nowhere because it wasn’t going to pass the Senate, and plenty of House Republicans thought it was too conservative too.

Rep. Goodlatte, the author of the bill, has promised to drop its most contentious parts — a requirement to electronically verify the immigration status of everyone working in the US and a program to provide guest workers for agriculture. Meanwhile, the “compromise” bill appears to have used Goodlatte’s bill as the basis for its own asylum provisions — meaning there’s not much daylight between the two there either. The big differences are these:

Much narrower legalization, with no access to green cards or citizenship, for DACA recipients. The Goodlatte bill provides only temporary legal status for some unauthorized immigrants who came to the US as children; they can renew it every three years but won’t be able to use it to apply for a green card, meaning they won’t have access to applying for citizenship.

But the requirements are narrower than the DACA requirements were — and it’s very easy to lose legal status once they have it. (Immigrants can lose their status, for example, if their income dips for too long below 125 percent of the poverty line.)

Criminalizing visa overstays. Entering the US illegally is a federal misdemeanor, but coming legally on a temporary visa and staying once that visa expires is not. Immigration hawks want to fix that, to make it easier to punish and deport the 40 to 50 percent of unauthorized immigrants who came on visas.

Deep cuts to family-based immigration — and minimal increases to employer-based immigration. The summary of Goodlatte’s bill brags that it would ultimately cut overall legal immigration by 25 percent — 260,000 fewer legal immigrants a year. It would do this by eliminating the diversity visa lottery and most existing categories of family-based immigration, including parents and adult unmarried children of US citizens. (Parents of US citizens would be eligible for renewable visas.) And it would expand employer-based green cards by fewer than 50,000 a year.

The path to passage for either bill is extremely narrow — but the pressure to pass a bill isn’t going away

Democrats appear prepared to vote en masse against both bills. That means that neither of them will pass unless Republicans vote overwhelmingly in favor — at least 218 of the House’s 235 Republicans would need to support either bill to pass.

So the question is whether Paul Ryan can hold the caucus together well enough to prevent fewer than 18 Republicans from voting no.

Goodlatte’s bill is assumed to be dead in the water. Even in the Trump era, many Republicans don’t mind legal immigration — or at least want to expand “merit-based” immigration instead of just cutting family-based immigration. Paul Ryan committed to bring it to a vote this spring to quell a revolt from the conservative House Freedom Caucus, but Republican leadership has been dragging its heels to actually build support for it — and now they have the compromise bill to push members to instead.

But there are a lot of Republicans who are hostile to “amnesty” — and a lot more who may not care about the issue but who don’t want to take a vote that can be used against them in the next GOP primary.

Republican leadership bet that the first group was smaller than 18 people, and trusted the White House would help them assure the second group that President Trump would provide cover. Except that Trump didn’t act as predicted — and it’s not clear how much trust a wary Republican should put in Friday’s belated assurances from members of the White House communications staff, claiming to endorse the bill on behalf of the president himself.

It’s going to be close, but it’s slightly more likely than not that both bills will fail. And even if the “compromise” passes narrowly, it’s unlikely to be a substantial enough margin to pressure Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who appears to believe his chamber is done with immigration for the year, to take it up (much less pressure Democrats out of mounting a filibuster in the Senate).

And if neither bill passes, the moderate Republicans — the ones who forced Ryan to agree to take bills up this week to begin with — will be back where they started. They’ll have to decide whether to give up or whether to take another stab at the discharge petition they circulated this spring, which would force Ryan to take up a series of bills including some that Democrats and moderate Republicans would both support — in other words, bills that could pass, if only they could get to the floor.

Sourse: vox.com