The flood of fiscal stimulus from the Republican tax cut bill is about to slow to a trickle.

It’s been just under a year since the GOP passed its $1.5 trillion Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which the White House and congressional leaders said would serve as a major boon to the economy, even promising it would pay for itself. (Most economists agree it won’t.) Though the bill did cut taxes for most Americans, it disproportionately benefits corporations and the wealthy.

But the juice it was supposed to inject in the economy will likely soon run out, just in time for the presidential election year.

The fiscal stimulus of the tax bill will come this year and next, but once 2020 arrives, many economists say the short-term growth effects will probably run out.

“It’s not done now,” Adam Looney, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former Treasury Department staffer, told me. “But its effect will fade out relatively quickly.”

The short-term effects of the bill are fading pretty fast

Goldman Sachs analysts said earlier this month in a note to clients that they expect the “positive growth effect” of a boost in federal spending and tax cuts under President Donald Trump’s administration will peak in the second half of this year and decline to “roughly neutral” by the end of next year.

The short-run effect of tax cuts is generally easy to spot — it means additional dollars in people’s and corporations’ pockets, increased economic activity, and more aggregate demand.

It makes sense that these effects run out quickly: If you have an additional $100 this year and you go out and spend it, your spending changes from one year to the next. If you spend that same $100 again the next year, but it’s not new, then your spending hasn’t changed.

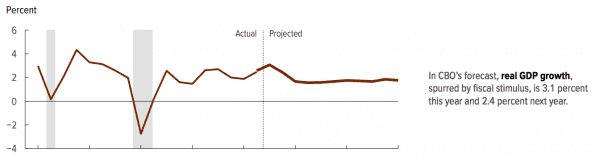

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that GDP growth, spurred by fiscal stimulus including the tax cuts and increased government spending, will be 3.1 percent in 2018 and will decline to 2.4 percent in 2019 as business investment and government purchases slow. It then projects that GDP growth will slow further to 1.6 percent each year from 2020 through 2022 and 1.7 percent annually from 2023 to 2028.

“Generally, we think of stimulus as sort of a rate of change concept relative to last year,” Joe Rosenberg, a senior research associate at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, told me. “You can think of the tax cut as a sort of one-time boost to people’s disposable incomes.”

Many Americans are seeing more money in their paychecks this year because of the tax cuts, which is where the stimulus is coming from right now. People won’t experience the new tax law in full until they complete their tax returns next year, and that could have positive or negative effects — if workers have been withholding too little under the new regime, they might owe more than expected, and if they’ve been withholding too much, they might get back more from the government than they thought.

“If refunds are large, that might provide an additional stimulus,” Rosenberg said.

The longer-term effects are usually a lot more subtle — and hard to spot

The argument for the tax bill’s long-term effects is that over time, as businesses and consumers have more money to spend, that will gradually lead to a better economy. Those who buy into such supply-side economic arguments, sometimes called trickle-down economics, say the tax cuts, especially at the top, will eventually make their way down.

“The story from the tax cut advocates for this bill and many prior bills has generally been one about the so-called supply-side effect of the tax cuts so that the tax cuts will encourage people to save and business to invest, and that will grow the economy over time,” Rosenberg said.

But historically, there’s not a ton of evidence that that’s worked — take, for example, the Bush tax cuts, which increased the deficit and debt and contributed to increased income inequality. And then came the Great Recession.

As Bruce Bartlett, a domestic policy adviser to President Ronald Reagan, explained in the Washington Post last year, the tax cuts in the early 1980s did have a positive effect on the economy, but aggregate real GDP growth was higher in the 1970s than in that decade, and falling interest rates and defense and highway construction projects contributed to the ’80s growth as well. When taxes went up under the Clinton administration in the 1990s, growth went up, and after the Bush tax cuts, it went down.

Corporate tax revenues for the government are down one-third from last year, due in large part to the tax bill, which reduced the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35 percent.

For the tax bill to spur major economic growth, corporations would have to pass on the savings to workers and make big increases in their investments. But that’s not really what’s happening, at least not yet.

As Jim Tankersley and Matt Phillips recently outlined for the New York Times, it’s not yet clear what exactly companies are doing with all their newfound cash. Capital spending picked up early this year, but business investment has been lukewarm. Stock buybacks that benefit investors and corporate executives are on the rise, and there have been a number of one-time bonus announcements, but wage growth hasn’t really picked up.

“Over the next couple of years, investment in wage growth and overall output will be ever so slightly higher than it otherwise would have been as the economy adjusts to the new tax law,” Kyle Pomerleau, an economist at the center-right Tax Foundation, said.

But that probably isn’t going to translate to the 3 to 4 percent sustained economic growth rate the Trump administration keeps promising. Nor does it mean, as some Republicans have contended, that the deficit-increasing tax cuts will pay for themselves.

“Economists all know the answer to that already, and the answer is no,” Looney said.

Sourse: vox.com