S 1, the very first bill the new US Senate considered in 2019, had nothing to do with ending the partial shutdown and reopening the government. It was instead a grab bag of different proposals related to the Middle East, and a controversial one at that. Most of the debate centered on Title 4 of the bill, a provision that would give states a legal blessing to punish companies that choose not to do business with Israel or Israeli-owned enterprises, a key demand of the pro-Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

Twenty-six states have adopted laws that punish companies that choose to boycott Israel. Defenders of the law see them as necessary to protect an ally from hostile activists, while critics argue that the laws are unconstitutional infringements on free speech. So far, the only two federal courts to consider such bills have sided with the critics; Title 4 is designed to provide more legal cover for state BDS laws in future hearings.

Historically, pro-Israel bills have sailed through the Senate (and the House). But this time, there was a twist: The bill, written by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), lost a vote on the Senate floor on Tuesday night. Forty-three Democrats banded together to filibuster it, enough to block the bill from moving forward for the time being.

The immediate reason for the bill’s defeat was the shutdown: Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer is refusing to pass anything until the government is reopened. But the controversy that surrounded it also speaks to the larger concerns about how state-level anti-BDS laws, which can apply to individuals working as independent contractors, have been used to repress free speech rights.

Even more broadly, the fact that this bill was controversial at all reveals how the politics surrounding Israel is changing. Support for Israel, so long a bipartisan issue, is becoming polarized, with Republicans willing to back Israel virtually unconditionally while Democrats are more willing to question Israeli policy and US support for it.

The two parties’ approaches to Israel are changing, and faster than some may have anticipated. The fight over the anti-BDS bills shows how.

What anti-BDS bills do

BDS, a loose movement that dates back to roughly 2005, aims to force Israel to change its approach to the Palestinians through external pressure. BDS activists want companies to stop doing business in Israel, consumers to stop buying Israeli products, and academics and cultural figures to stop collaborating with Israeli colleagues. The movement’s supporters bill it as the spiritual heirs of the boycotts targeting apartheid South Africa in the 1980s; its opponents bill it as an anti-Semitic campaign aimed at the destruction of Israel as a Jewish state.

The pro-Israel community in the United States has made combating the BDS movement one of its principal goals in recent years. They’ve had a lot of success, particularly at the state level. Some 26 states, from New York to Texas to Rhode Island to South Carolina, have regulations on the books that use state financial power to block BDS activists from accomplishing their goals.

These state anti-BDS regulations, implemented through either legislation or a governor’s order, require businesses contracting with the state to affirm that they are not participating in a boycott of Israel. In essence, they force companies to make a choice between participating in BDS and keeping their business with 26 different state governments. Guess what most companies are going to pick?

The federal government does not, as of yet, have an equivalent policy in place. There were some attempts to design one, but the Combating BDS Act is not one of them. Instead, it’s designed to give legal cover to the various different state BDS laws, protecting it from a particular kind of constitutional challenge. The idea, as the anti-BDS law American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) explains, is to encourage more states to adopt anti-BDS legislation by assuring them it’s legal to do so.

The issue is the constitutional doctrine of “preemption,” which holds that when state and federal laws conflict, the federal law takes precedence. In this case, it’s possible that a court might hold that the state BDS laws are implicitly preempted by federal law, because foreign policy powers reside with the federal government and Congress has chosen to do nothing on this issue.

The Combating BDS Act attempts to head off this argument. It explicitly clarifies that state BDS laws are “not preempted by any Federal law” in Subsection E, giving them free rein to continue pursuing anti-BDS action.

“The purpose of this law is to say … we want the courts to know that we, Congress, are giving the states permission to do this,” David Bernstein, a George Mason law professor who has written about anti-BDS laws, tells me.

So the Combating BDS Act, a version of which was co-authored by Rubio and conservative Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin (WV) last year, doesn’t actually impose new restrictions on BDS advocates. It just gives legal cover to states that have already done this, which implicitly encourages other states to do the same. The law’s proponents see this as a measured and necessary step in pushing back against what they see as unfair and illegitimate demonization of Israel.

“My bill doesn’t punish any political activity,” Rubio wrote in a tweet defending his bill. “It protects the right of local & state [governments] that decide to no longer do business with those who boycott #Israel.”

In the past, such a limited measure might not have been so controversial. But a few things have come together to cause the bill to fail.

Why Democrats are fighting it

Two progressive senators were particularly outspoken in opposing the Rubio bill: Sens. Bernie Sanders and Dianne Feinstein. Neither of them has outright defended the BDS movement but instead attacked anti-BDS laws on free speech grounds.

“This Israel anti-boycott legislation would give states a free pass to restrict First Amendment protections for millions of Americans,” Feinstein wrote in a press release. “Despite my strong support for Israel, I oppose this legislation because it clearly violates the Constitution.”

The state laws do not explicitly prevent individual citizens from joining the BDS movement — that would almost certainly be unconstitutional. But that’s been the effect in practice, in part because of how they apply to individuals who are independent contractors.

Consider the case of Bahia Amawi, a speech therapist in Texas who had chosen to personally boycott Israeli-made goods. Amawi is not a state employee but an independent contractor who signed an annual agreement with the school district in the city of Pflugerville. Because Amawi was a contractor, her agreement with the state was subject to the state’s anti-boycott legislation, just as a contract with a major corporation would be.

This meant that Amawi — as the sole proprietor of her contracting business — was forced to pledge not to “take any action” that was “intended to penalize, inflict economic harm on, or limit commercial relations with Israel.” Amawi did not want to sign away her right to boycott Israel, and she did not renew her contract with the Pflugerville schools. In essence, she was being forced to choose between her free expression and her livelihood. That, civil liberties advocates say, is a clear restriction on free speech.

“Sole proprietors can’t neatly distinguish between their individual actions and their business activities,” Brian Hauss, a staff attorney at the ACLU, told me. “What these laws say is that if you get even one cent of state money, you’re prohibited from boycotting across the board.”

Hauss and his ACLU colleagues have brought suits against several different state BDS laws on First Amendment grounds. The two federal judges who have ruled on these cases so far sided with the ACLU and their clients, issuing injunctions blocking Kansas and Arizona from implementing their anti-BDS laws.

Amawi’s case, widely reported in December, and other similar ones have galvanized liberal opposition to the anti-BDS laws. While BDS itself splits left-liberals, it’s much easier to get Democrats to agree that people should have the right to participate in the BDS movement if they’d like. The fact that some of these state laws are so broadly worded as to apply to people like Amawi has turned them into a lightning rod, making enemies out of national Democrats who might otherwise be willing to vote for the Rubio bill.

But the broad opposition to the bill isn’t just the fault of overeager state legislators. Rubio and Senate Republicans also made a serious tactical error: introducing the bill during the government shutdown.

Congressional Democrats are currently laser-focused on their battle with Trump over border wall funding and reopening the government. Out of both principle and political expediency, Senate Democrats don’t want to consider any bills until the government is back in business. This goes double for a bill like the Combating BDS Act, which divides Democrats among themselves.

As a result, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer — a pro-Israel hawk who actually co-sponsored a 2017 anti-BDS bill very similar to the current one — told other Democrats that he was planning to vote against moving forward with consideration of S 1. Other relatively pro-Israel Democrats, like Maryland Sen. Ben Cardin, took a similar position.

As a result, the Democrats like Sanders and Feinstein who opposed the substance of the bill weren’t alone. Principle and political expediency combined to unify the caucus, leading to S 1 being blocked. Republicans and state legislators both appear to have screwed this one up.

The big picture: Israel has never been so divisive in modern political history

Rubio was not happy about the way things went down. In a tweet sent on Monday morning, he claimed that Democrats were blocking his bill because many of them secretly support the BDS movement.

“A huge argument broke out at Senate Dem meeting last week over BDS,” he tweeted. “A significant number of Senate Democrats now support #BDS & Dem leaders want to avoid a floor vote that reveals that.”

But there is no evidence that any Democrats in the Senate support BDS; every one who has taken a public position on the movement has opposed it. Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) called on Rubio to take down the tweet, telling his colleague that “you know it isn’t true.” And a senior Democratic Senate aide disputed Rubio’s characterization of the Democratic meeting last week about the bill, accusing Rubio of having sour grapes about his bill’s failure.

“It was clear as of [Monday] morning that the Republicans did not have the vote for cloture,” the aide told me. “That’s part of what contributed to Sen. Rubio’s Twitter tantrum.”

But while Senate Democrats aren’t BDS supporters, two first-term House Democrats — Reps. Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib — are. The fact that these two women are in Congress, together with the Senate’s hand-wringing over the Combating BDS bill, points to a real change in the politics surrounding Israel.

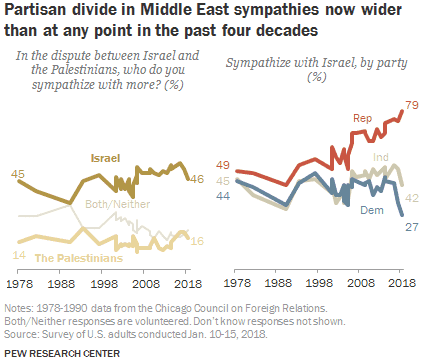

Last January, Pew released a poll on Americans’ partisan opinions on Israel. It found the widest divide between Republicans and Democrats in the 40 years it has been collecting data:

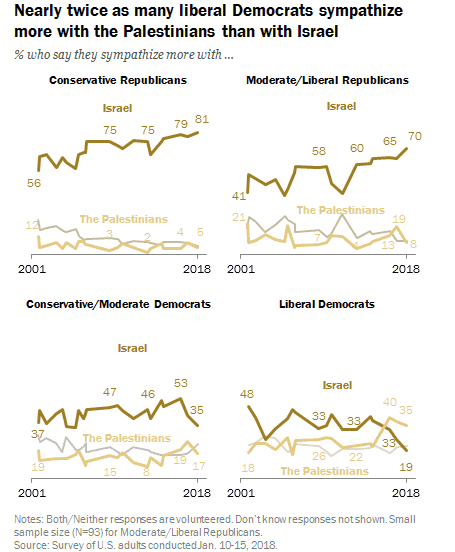

What you see there is an issue that used to be widely bipartisan growing more and more divisive over time. And when you dig into the data further, you find that liberal Democrats — the party base, the people disproportionately likely to turn out in primaries and donate to candidates — have come to sympathize far more with Palestinians than with Israelis:

The change in partisan opinions on Israel reflects a number of factors. First, the rise of evangelicals and Christian Zionism as a force in the Republican Party, together with the post-9/11 war on terror, turned Republicans into an exceptionally hardline pro-Israel party. But in a hyperpolarized political environment like the modern United States, partisanship is zero-sum: When one party champions something, it necessarily turns off partisans of the others from the same cause.

The last Democratic president, Barack Obama, also clashed repeatedly with his Israeli counterpart, conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Netanyahu even went so far as to scheme with Republicans to deliver a speech to Congress against the Iran nuclear deal, Obama’s signature foreign policy accomplishment. Israel’s prime minister working with Republicans to whip up opposition to Obama, together with other fights between the two leaders, alienated both congressional and rank-and-file Democrats.

But most fundamentally, Israeli politics has left the Democratic Party behind. Israel’s center-left Labour Party has not won an election since 1999. Its occupation of the West Bank has continued apace, as has construction of settlements. The current government is arguably the most right-wing in Israel’s history; the two-state solution has never looked further away.

This is all alien to an increasingly liberal Democratic Party, one in which the social justice and socialist lefts — which have long sympathized with the Palestinian narrative — have more and more influence. Many Democrats no longer see Israel as an embattled Middle Eastern democracy and a haven for the oppressed Jewish people; they see a military giant that is occupying Palestinian territory and breaking up peaceful Palestinian protests using force.

All these factors — political partisanship, the Obama-Netanyahu fight, and the right-wing drift in Israeli politics — have put pressure on Israel’s defenders in the Democratic Party. Currently, we have a situation where many elected Democrats see support for Israel as a bipartisan value, while their rank-and-file voters do not.

This state of affairs, a party at odds with its voters, is by its nature unstable. The defeat of the Combating BDS bill, while not explicitly about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict per se, is a sign that the Democratic Party can no longer be counted on to back any bill merely because it’s seen as “pro-Israel.”

Sourse: vox.com