The idea of a universal basic income — a check sent out by the government to every American, no strings attached, just for being alive — is sometimes decried as un-American, as a way for people to get money they didn’t work for.

But America contains one of the few places the policy has been tried at scale: Alaska.

The Alaska Permanent Fund is a state-owned investment fund established using oil revenues. It has, since 1982, paid out an annual dividend to every man, woman, and child living in Alaska. In 2015, with oil prices high, the dividend totaled $2,072 per person, or $8,288 for a family of four. By 2017, it had been cut down to $1,100 due to money being diverted to other purposes; in cheaper gas years, it can dip into the $800 to $900 range.

That’s not a living wage by any means, and it arguably doesn’t satisfy the “basic” requirement of “universal basic income.” But it’s a truly universal cash transfer program, the only one of its kind to be implemented in the United States, and it almost always offers families enough to eliminate desperate $2-a-day cash poverty.

Decades of conservative critics have decried cash programs like Aid to Families With Dependent Children or Social Security Disability Insurance, as vigor-sapping, soul-deadening subsidies for moochers, economic disasters that stunt growth and encourage sloth.

So economists Damon Jones of UChicago and Ioana Marinescu of UPenn decided to figure out if Alaska’s cash payments were discouraging Alaskans from working. Their conclusion: not really. They find that “the dividend had no effect on employment” overall.

In other words: Alaska has figured out a way to use its oil wealth to give all its residents cash for free and wipe out extreme poverty — and it doesn’t appear to be harming its economy in the process.

Cash transfers didn’t lead to fewer working Alaskans

The challenge, in evaluating the effects of Alaska’s cash payments, is finding a baseline to which to compare the state’s outcomes. You can’t just compare Alaska after the policy was implemented in 1982 to Alaska before that, as there are plenty of other differences between the Alaskan economy in, say, 1981 versus 1983 (the US was in recession in 1981, for instance). And there’s no state that’s otherwise identical to Alaska that didn’t enact the policy to use as a baseline. Alaska is, as any resident will tell you, its own beast.

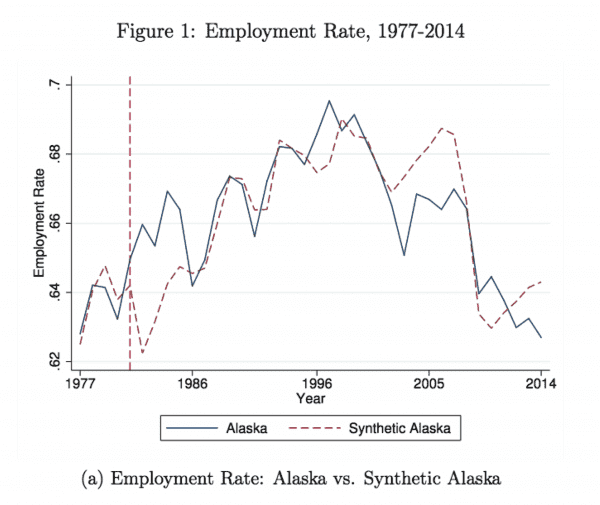

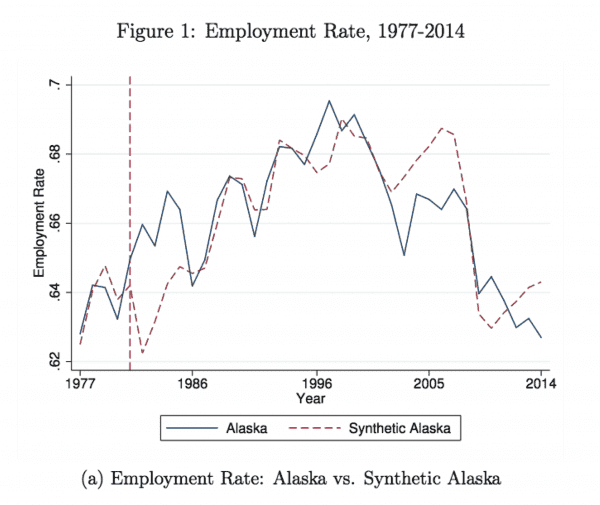

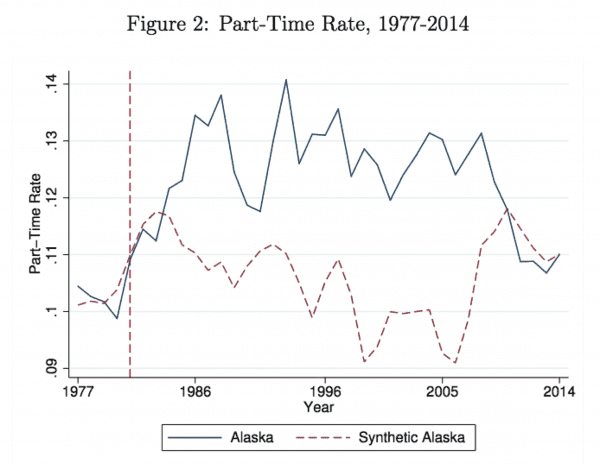

So Jones and Marinescu employ what’s known in the social sciences as a “synthetic control” method. Basically, they combine a number of other states whose patterns of employment, part-time work, and related statistics roughly match Alaska’s in the years before the policy was enacted. None of the states alone is a good comparison, but if you combine them carefully, you can come up with a “synthetic Alaska” for comparison.

Here’s how employment rate — the share of people currently at work, as a share of the overall population — evolved in Alaska versus synthetic Alaska, before and after 1982:

There really isn’t much difference. Some years Alaska has higher employment than its synthetic counterpart, other years it doesn’t, but overall, they remain very close to each other. The cash payments don’t appear to have much effect.

To test how robust their findings are, Jones and Marinescu also compared Alaska’s employment rate to that of every single other state as well as DC, using every year of data they have, from 1977 to 2014. That’s 1,836 comparisons. The average difference between Alaska and other states in all those comparisons is -0.0004, vanishingly close to zero. That implies that their results aren’t just an artifact of which states they chose to be part of “synthetic Alaska.” The state just didn’t become an outlier with unusually high or low employment as a result of the Alaska Permanent Fund dividends.

They repeat the analysis for labor force participation — the share of the population either working or unemployed and actively looking for work — and similarly find no difference.

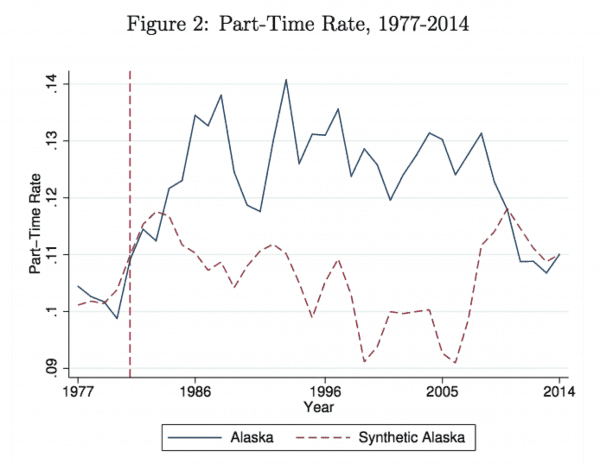

Where they do find a difference is part-time work, which increases in Alaska, compared to synthetic Alaska, after the cash payments are introduced:

The increase in part-time work isn’t huge — Jones and Marinescu estimate the increase in the share of the population that works part time to be around 1.8 percentage points — but it’s real.

There are two things that could be going on here:

They find some evidence for the latter effect. “Some specifications suggest a marginally positive employment effect, which, in combination with the increase in part-time worked, could indicate new entrants into employment who work part-time,” they write.

That said, they also find evidence that the checks, on the margins, reduced work hours. But they conclude that this was mostly offset by the increased spending the checks enabled, which in turn helped businesses hire more.

When they split up businesses into “tradable” ones (like logging or oil extraction) that primarily sell their products to people and businesses outside Alaska, and “non-tradable” ones (grocery stores, accountants, landscaping) that sell only within Alaska, they found that employment rates at the latter held constant, and part-time work didn’t increase. That is, companies that benefited from new spending as a result of the checks didn’t cut employment at all. By contrast, part-time work did increase, and employment fell, in companies that sold goods outside Alaska, and so didn’t benefit from their customers suddenly having more money.

Alaska’s policy is unusually good and hard to replicate

“A universal and unconditional cash transfer does not significantly reduce aggregate employment,” Jones and Marinescu conclude. It’s an important conclusion, and one that other research, studying everything from “negative income tax” experiments in the 1970s to programs in Iran and at Indian reservations, confirms.

There just doesn’t seem to be much evidence that giving people a modest amount of cash stops them from working entirely, or leads them to work significantly less.

But there’s a big caveat: Alaska pays these checks out of an investment fund financed by oil money. Taxing or collecting royalties for natural resources is just about the best way for the government to pay for stuff. Oil is in the ground, there’s a limited supply of it, and taxing it doesn’t reduce the amount left in the ground. It might reduce companies’ incentive to bring it out of the ground, but frankly, given climate change, that’s probably a good thing. Relying too heavily on oil money can cause political dysfunction, but distributing the money as cash to citizens helps reduce opportunities for corruption.

With exceptions like Texas and North Dakota, the rest of the US doesn’t have those kinds of oil reserves, which makes the math of financing a similar policy at the federal level tough. Hillary Clinton considered proposing a national expansion of the Permanent Fund under the title “Alaska for America” during the 2016 campaign, but couldn’t make the financing work.

Realistically, a similar policy at the national level would probably be funded the way the rest of the federal government is, with a mixture of income, payroll, and corporate taxes. Those are perfectly fine taxes, but standard economic theory predicts that raising them will, on the margin, discourage work, which might result in different effects on employment than Alaska’s policy has had.

But a similar policy financed by hyper-efficient taxes — like ones on land value, carbon emissions, alcohol, cigarettes, gasoline, and sugar — would likely do what Alaska’s policy does: reduce poverty, boost average incomes, and not harm the economy in the process.

Sourse: vox.com