Fans of Gilded Age political economy got a rare treat this past weekend when in the course of a rambling two-hour discourse at the Conservative Political Action Committee’s annual gathering President Donald Trump made reference to the Great Tariff Debate of 1888.

The lead-up was Trump praising himself for finding some dormant legal authority he could use to unilaterally impose tariffs without congressional agreement.

“I found some very old laws from when our country was rich — really rich,” he said. “The old tariff laws — we had to dust them off; you could hardly see, they were so dusty. But, fortunately, they weren’t terminated.”

These old laws that he was able to use, according to Trump (though not in reality), date back to an earlier time when, according to Trump (though not in reality), the United States was richer than it is today. And according to Trump, his trade policies will bring us back to that prosperity.

Very little of Trump’s accounting of what happened in that period is accurate, including how the tariff scheme of William McKinley really played out in the late 19th century. And while tariffs were a central issue of the 1888 presidential race, the contours of the debate aren’t particularly relevant to the key matters at hand in 2019. Tariffs also proved politically toxic, and Republicans were crushed in the 1890 midterms.

Mostly, Trump’s interest in the era is a powerful reminder of his unusual ability to be totally obsessed with trade policy without actually knowing anything about it — or caring to learn.

What Trump thinks happened in 1888

The whole swath of presidents between Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt is often forgotten in historical memory (many are referenced in the amusing Simpson’s musical number about America’s forgotten presidents), and there’s a tendency to think of this whole period in American politics as much ado about nothing.

But it was, in fact, a time of vigorous partisan contestation with ferocious debates about voting rights, monetary policy, and of course the tariffs that really were the leading issue in the 1888 presidential race.

Here’s how Trump remembers it:

This doesn’t appear to be something McKinley really said, but it is true that there was a major political debate in the late 1880s about what to do with tariff revenue. It’s not particularly clear what this debate has to do with any issues in 2019, but Trump’s interest in the matter seems to reflect his (outdated even in the late 19th century) preoccupation with the revenue implications of tariffs.

What the 1888 tariff debate was about

Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 led to the secession of Southern states from the Union, which in turn had the effect of giving the new Republican Party very large congressional majorities, thanks to the withdrawal of Southern Democrats from Congress.

During the war and Reconstruction years, those Republican majorities acted to — among other things — impose high taxes (aka tariffs) on imported foreign goods. This was a longstanding idea of first the Federalist Party and then its successor the Whig Party and then its successor the Republican Party, all of which believed (following Alexander Hamilton’s lead) that a protective tariff would encourage the industrialization of the United States. Against these various parties was counterpoised the more agrarian Democratic Party, which preferred cheap imports and felt that promoting industrialization by taxing the country’s rural majority was backward and regressive.

High tariffs also meant high tariff revenue, which was useful for fighting a war and then for paying off wartime debts. But by the 1880s, the country was simply piling up budget surpluses.

Democrats argued that the persistent surpluses showed that the country was overtaxed and proposed to cut tariffs and reduce revenue, cutting prices to consumers and making Americans better off. Republicans, in turn, offered two somewhat contradictory ideas — one was that the country should increase spending by enacting a more generous pension program for Civil War veterans and the other was that the country should cut revenue by making tariffs even higher.

This was essentially a Laffer Curve argument in reverse. If the protective tariff was bringing in lots of revenue, the argument went, that meant it wasn’t doing a good enough job of dissuading people from buying foreign imports. What the country needed was taxes on imports so high that Americans would have to buy domestically produced goods, leading the Treasury to forego tariff revenue.

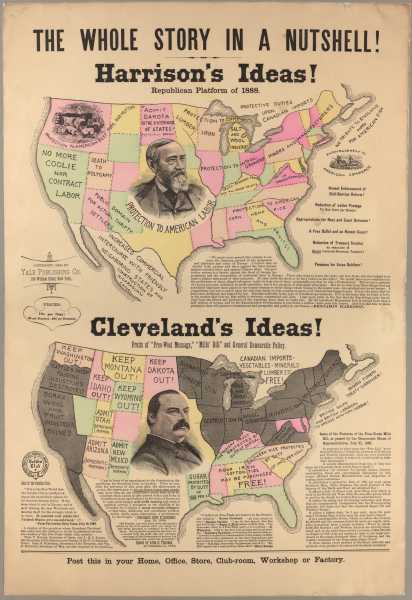

This became the main question in the 1888 presidential election, with incumbent President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, pushing for tariff cuts and Republican challenger Benjamin Harrison calling for higher tariffs. Most voters sided with Cleveland, but Harrison won the Electoral College (though had black votes in the South not been suppressed by terrorist violence, Harrison would likely have won the popular vote), and Republicans set about to enact their program.

Republicans were wrong (or maybe lying)

This whole episode, complete with the name Great Tariff Debate, is memorably recounted in Douglas Irwin’s 2017 book Clashing Over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy.

As Trump does not read books, it is extremely unlikely that Trump has read Irwin’s book, but he seems to have heard something about it second- or third-hand. Irwin’s conclusion, however, going back to a 1997 scholarly paper he wrote, is that Republicans were wrong — to reduce revenue, the US needed to cut tariffs, not raise them.

In a bit of a historical irony, however, when Harrison got around to signing the 1890 tariff-hiking legislation sponsored by McKinley it actually wound up modestly reducing tariff revenue because even though taxes on most goods rose, the tax on raw sugar — the single most lucrative tariff of the whole bunch — was cut.

Raw sugar is not an industrial product at all. So cutting tariffs on sugar imports while greatly increasing them on manufactured goods was entirely consistent with the GOP’s priority of redistributing income away from agriculturalists and toward manufacturing. But structuring the tariff program in this way suggests that the whole surplus issue was something of a red herring. Besides, the other thing Republicans did was pass the Dependent and Disability Pension Act for Union veterans.

Even the sugar tariff cut, as it happens, was in service of promoting American manufacturing. McKinley drafted the legislation to allow Harrison to selectively reimpose the sugar tariff on any country that refused to alter its trade policy to be more open to US manufacturing exports. This strategy worked, and Latin American sugar exporters agreed to cut their own tariffs on manufactured goods, thus ensuring that American manufacturers got both protection from foreign manufacturers and a boost in their access to foreign markets.

To make a long story short, the Harrison administration’s economic policy was indeed broadly Trumpy in nature. Though what about this serves to make Trump’s approach look more attractive is unclear.

The McKinley Tariff Act was an unpopular disaster

Had Trump read more deeply about the Gilded Age, he might know that the McKinley Tariff Act was unpopular and that its unpopularity, combined with the shockwaves of a financial crisis in England, led the Republicans to a crushing defeat in the 1890 midterms.

Republicans lost four Senate seats (two to the Democrats and two to the Populist Party which, contrary to modern usage of the term “populist,” was a free-trade party) and a staggering 86 House seats. Two years later, Cleveland swept back into office with convincing wins in both the popular vote and the Electoral College, and Democrats gained more Senate seats, giving them unified control of government for the first time since the Civil War.

Far from ensuring prosperity and political success, in other words, the McKinley Tariff contributed to economic problems and dealt the Republican Party its worst results of a generation. None of that exactly proves that Trump’s tariff enthusiasm is mistaken, but it does seem like an odd example for the president to pick. Then again, the president capped off his discussion of this matter with a fabricated McKinley statement, so there’s no particular reason to expect anything else he has to say about it to make sense.

Sourse: vox.com