Most media coverage of America’s demographic future sees the country approaching a significant tipping point over the course of the next generation, with headlines like the Associated Press’s “Census Bureau estimate: Whites won’t be majority by 2044” typical of the genre. The Census Bureau itself somewhat encouraged this kind of coverage of its 2014 demographic projections, doing things like releasing an infographic titled “Projecting Majority-Minority: Non-Hispanic Whites May No Longer Comprise Over 50 Percent of the US Population by 2044.”

There is, however, another way of looking at it. The very same census report projects that as far out as 2060, 68.5 percent of the population will be white. It’s just that a reasonably large share of the white population will be partially descended from Latin American immigrants. A further 6.2 percent of the population will belong to “two or more races,” with a large share of those likely identifying at least in part as white.

The difference here is between an exclusive and inclusive definition of whiteness. It’s clear that in the face of rising intermarriage rates, a larger share of the population will be at least partially descended from Asia or Latin America, while the partially black share of the population will grow at a more modest rate.

But many of these people will, like me, be of predominantly European ancestry and have skin tone and other facial features that fit comfortably within the conventional boundaries of whiteness. If you use the exclusive version of whiteness — in which anyone who’s part anything is perforce not white — then you get a majority-minority America by 2044. If you use an inclusive view and let anyone who identifies as white be white, then America remains majority white indefinitely.

And a new study from Dowell Myers and Morris Levy, a demographer and a political scientist at USC, respectively, suggests that the media’s choices about how to characterize it make a real difference to people’s political response to these demographic trends.

In essence, media narratives that take a narrow view of whiteness and suggest that the falling share of 100 percent Europeans in the population means the end of America’s white majority generate “much higher levels of anger or anxiety” than alternative (and, frankly, more plausible) characterizations of the situation. The implication is that a premature rush to proclaim the end of white America, even when intended in a celebratory manner, may be fueling racial backlash politics.

There are different ways to describe the same data

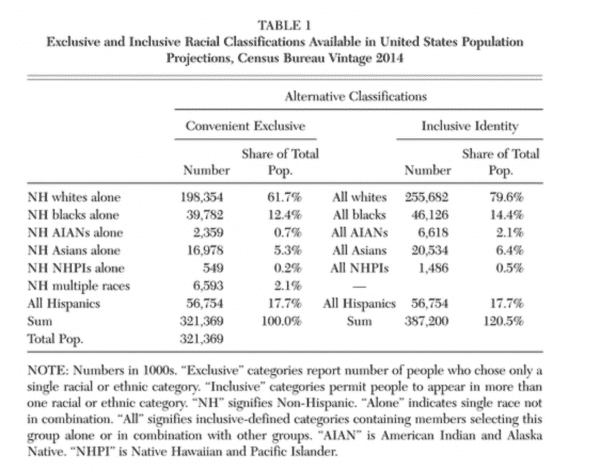

There are a lot of different ways one can count up America’s racial demographics, but one simple choice is whether you make people select a single racial identity (i.e., you are either Hispanic or black) while creating a catchall multiracial category for people who identify that way. This “exclusive” account of demographics has the convenient property of making sure the numbers add up to 100 percent.

A different, “inclusive” account allows for the fact that a person of mixed ancestry might identify as white and as Asian and that many people who identify as Hispanic also identify as white or black or Native American. These two methods lead to very different characterizations of the present-day white share of the population, which is either an overwhelming 80 percent of the public or else a tenuous majority of 62 percent:

This effect seems to be primarily driven by allowing for Hispanic identity to overlay on a racial identification, and secondarily by the different way it treats mixed-race people.

Neither characterization is exactly right or wrong, but they both capture different dimensions of the issue. And projecting them into the future leads to very different accounts of future US demographics: On the exclusive reading, the white population is going to slip below 50 percent relatively rapidly, while on the inclusive reading, that date is pushed into the distant future and may in fact never occur. And the psychological impact of hearing those different stories appears to be very different.

Inclusive stories promote hope; exclusive ones promote anxiety

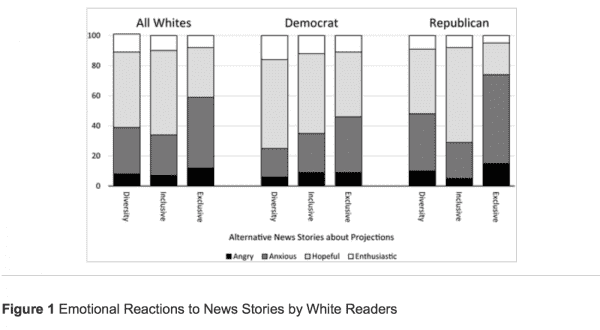

The researchers conducted an experiment by randomly assigning various white people to read three different faux news accounts of the Census Bureau’s projections. One story simply noted that diversity was rising, a second cited the data that results from using the inclusive definition of whiteness, and a third emphasized the exclusive definition of whiteness and therefore forecast a white minority by 2044.

They then asked readers how they felt and found strikingly different responses to the different narratives. In essence, the stories that emphasized the inclusive definition made white people feel hopeful for the future, while those that emphasized the exclusive one made white people feel anxious. The diversity narrative was polarizing, generating anxiety among white Republicans but hopefulness among white Democrats for an overall hopeful reaction, though less so than the inclusive narrative.

The partisan differences here are noteworthy, but so are the similarities. The anxious reaction to the exclusive narrative was strongest among Republicans, but it’s noteworthy that it exists among almost half of white Democrats as well. People who are primed to feel anxious about white people losing majority status, in other words, can’t be easily written out of the Democratic Party coalition as deplorable racists without significantly shrinking the party.

The good news is that while exclusive accounts have been a more typical media narrative, inclusive ones are more likely.

The boundaries of whiteness have historically been fluid

As Jamelle Bouie wrote in a 2014 essay on the demographic drivers of American politics, “ethnic identity is fluid — it shifts and changes with the circumstances of society.”

At various times in American history, the ethnic differences between Irish and Anglo-Scottish people or between immigrants from northwestern Europe and those from the south or east have loomed very large. But over time, Jews, Slavs, Italians, Irish, and others “became white” through a joint process of assimilation of minority groups into mainstream culture and accommodation by the mainstream of divergent practices.

Once upon a time, the Catholic religion was broadly regarded as vaguely un-American. And as recently as my grandparents’ lifetime, pizza was covered in the New York Times as an exotic ethnic food that required a more detailed description than we would give these days to tacos or pad thai.

Especially in light of the high intermarriage rates, it seems extremely likely that a similar process will continue into the future and America’s demographic trajectory will look more like the inclusive narrative than the exclusive one.

These days, lots of white people would say their background is Italian and English or Irish and German rather than one or the other, but they also wouldn’t see themselves as belonging to an exotic “mixed ethnicity” category. It’s simply the case that in American society, it’s common for people to be able to trace their ancestry in more than one direction.

In the future, the same basic reality is likely to apply to people who have one grandparent from Cuba (like me!) or China just as much as it does to people with one grandparent from the Czech Republic.

One thing this means, as Bouie’s essay argued, is that the Republican Party’s status as the party for white people is probably more tenable over the long term than a lot of contemporary takes argue. But the other thing it means is that white Americans don’t need to fear that the country is on the verge of some kind of racial tipping point. The country is unquestionably changing, but it’s always changed over time.

Somewhat ironically, though, media narratives that emphasize the tipping point idea fuel backlash politics that, in turn, probably harden ethnic dividing lines and make the process of mutual accommodation more difficult.

Sourse: vox.com