Republicans promised that last year’s massive corporate income tax bill would lead to a surge in investment and thus bigger paychecks for working Americans. Instead, it’s been a boon to shareholders.

A Bloomberg analysis shows that of America’s $54 billion corporate tax windfall, so far $21.1 billion has been kicked to shareholders in the form of “buybacks,” almost twice as much as has gone to employees in higher compensation and far more than has been spent on capital investments or research and development.

Denouncing this trend has become commonplace Democratic messaging. But what are they going to do about it?

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) is unveiling legislation today that stakes his claim on where the Democratic Party should take the fight over the economy. The bill, which he previewed to Vox, would curb how companies do buybacks, forcing them to cut in workers on the action. The Worker Dividend Act would mandate that companies buying their own shares must also pay out to their own employees a sum equal to the lesser of either the total value of the buyback or 50 percent of all profits beyond $250 million.

Most significantly, though, Booker’s bill isn’t a critique of the GOP tax bill. It’s a critique of the overall operation of an economic system that people on the left have long argued is systematically broken and stacked against everyone but the very wealthiest Americans.

The bill doesn’t have a snowball’s chance in hell in GOP-controlled Washington. But it sends a message from Booker, a rising party star once better known for defending the private equity industry, about where he wants the party to go.

“It’s a commonsense move to address a variety of ills,” including underinvestment and low pay, Booker tells Vox. It’s also a way to “begin to shine a light on how different the economic system has become over the decades. There are policy decisions we have made that led to stagnant wages.”

Booker is reinventing himself as a populist crusader, challenging regulators to start paying attention to how corporate concentration can harm workers. He’s been scathingly critical of bipartisan efforts to water down Obama-era Wall Street regulations. He joined with Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) to take aim at noncompete agreements between retail chains.

And with his new bill, he is striking at the conceptual heart of the current American economic model, one that puts short-term rewards for shareholders above every other stakeholder, including the workers at the bottom.

Back up a minute — what’s a share buyback?

Beginning in the New Deal era, share buybacks were, for decades, considered a form of illegal stock market manipulation — a way for executives to pump up share prices without doing anything to improve their underlying business.

When companies first go public (i.e., stage an initial public offering), stock is made available for purchase by the broad public on the main stock markets. In principle, the sale of the stock can be used to raise money for investment. More typically, the point of the IPO is to give the early investors in the company — venture capitalists, early employees, and founders — the opportunity to get their hands on cash so they can begin to enjoy the fruits of their work.

A stock buyback is basically a secondary offering in reverse — instead of selling new shares of stock to the public to put more cash on the corporate balance sheet, a cash-rich company expends some of its own funds on buying shares of stock from the public.

Why? There are two reasons. One is that it puts cash in the hands of those shareholders who choose to sell in the buyback. And two, it decreases the number of shares, potentially hiking up company’s share price.

In 1982, the Securities and Exchange Commission created a legal process for buybacks, Rule 10b-8, ending their decades-long ban. The rule was modified somewhat in 2003 after the wave of accounting scandals associated with Enron.

Profitable companies have long had the option of kicking cash to shareholders in the form of dividends. Buybacks were simply a new tool to accomplish that same goal, and in many ways, they were a better tool because for much of that period, the capital gains tax rate was lower than the dividend tax rate.

Fundamentally, for 30 years, or so the practice was wholly embraced by the political mainstream. What’s significant about the Booker bill, then, is not only the specifics of the legislation. It’s the broader picture that a once-marginal viewpoint about the relationship of Wall Street to business is rapidly moving toward the Democratic Party mainstream.

His bill would let companies continue to do buybacks if they wanted, but they’d need to cut workers in on the loot. Booker’s team calculates, for example, that a company like Walmart, which did $4.1 billion worth of buybacks in fiscal year 2016, would have to offer $2,928 in bonuses to each of its 1.4 million employees.

The case for buybacks

During the congressional debate over the tax bill last year, Republicans emphasized the legislation’s (temporary) benefits for middle-class taxpayers. During the final weeks of the year, as companies rushed out press releases crediting Trump for their year-end bonuses, they emphasized the bonuses.

But as it’s become clear that flushing out cash to shareholders is, in fact, the main consequence of the tax bill, Trump administration figures are increasingly comfortable admitting that this was their intended effect all along.

“Even if people buy back stock, that is money that goes back into the economy that lets investors take that money and allocate it to other things,” Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin argued at a late-February Chamber of Commerce event. “It’s a complete system.”

And this is the orthodox view in the business world and on Wall Street. Financial markets exist to allocate capital (i.e., money) “efficiently.” That means it’s good when money flows off the books of major companies and into the hands of wealthy investors. They then reinvest the money in other things, by buying other stocks or bonds or what have you.

It may be true that in narrow distributional terms, buybacks don’t do much to help the average middle-class person — about 80 percent of the shares of stock in the country are owned by 10 percent of the population, with the bottom half of the income distribution owning basically nothing. But in the long run, facilitating the more efficient allocation of financial capital grows the economy and creates broadly shared prosperity.

The skeptics’ case

Skepticism about the merits of this case takes a variety of forms.

One conceptually restrained contrary argument comes from Jason Furman, a Harvard professor who served as the Obama administration’s top economist. In a paper for the Peterson Institute for International Economics, he observes that even the most optimistic estimates of the growth impact of tax changes are modest, typically claiming to raise total national income by less than 1 percent.

By contrast, the distributive impact of tax policy is huge — with Obama administration initiatives enacted in 2009 and 2010 raising incomes for the bottom 40 percent of the population by between 6 and 18 percent, while “no mainstream modelling of a tax plan has an effect close to as large, let alone one that would take effect immediately.”

On this view, it’s not so much that the growth case is wrong as that it’s irrelevant — the size of any growth gains is just tiny compared to the amount of money that’s being directly flushed out to wealthy shareholders, money that ultimately will be offset by cuts in programs used by the poor and the middle class.

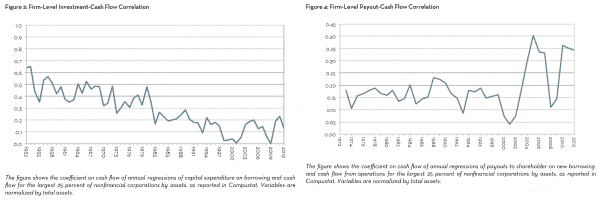

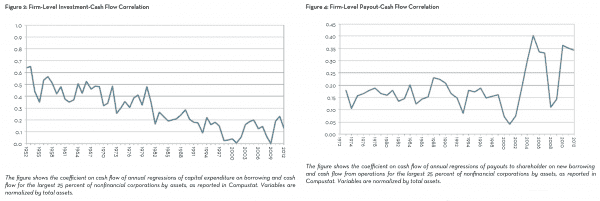

A stronger critique that began to wend its way from academia into the policy world thanks to a 2015 Roosevelt Institute paper from John Jay College economist J.W. Mason is that the rise of buybacks has actively harmed wages and investment. Mason shows that while there used to be an extremely strong correlation between corporate cash flow and business investment, that’s weakened over the years, even while the correlation between cash flow and payouts to shareholders has risen.

One can think of this as a kind of collective action problem. Most businesses would be better off on the whole selling goods and services in a higher-investment, higher-wage, higher-growth economy. But the short-term interests of any individual firm’s shareholders are best served by more financial payouts. And executives are both pushed (by “activist” hedge funds and leveraged buyout shops) and pulled (by compensation packages pegged to stock returns) to cater to shareholders’ needs.

“I’m a data guy,” Booker says, and looking at the data, he’s worried that today’s young people could be “the first ones that don’t do better than their parents” due to “decades of stagnant wages” driven in part by the fact that “short-termism is pervading so much of capitalism.”

The next economic debate

Most of the past decade’s worth of economic policy arguments have unfolded in the shadows of the Great Recession and focused on an urgent jobs crisis.

But with the labor market much improved from where it was two years ago and showing signs of continued strength, we now stand at something of a crossroads. One possibility is that with the pool of unemployed workers now much smaller than it once was, wages will begin to rise rapidly paired with investments in productivity-enhancing technology that make higher pay scales possible. If that happens, it’ll be good news for America — but bad news for fans of big ideas.

The contrary view notes that wage growth has been sluggish for a generation or two now, with stagnation punctuated only by the occasional asset price bubble. It also asks whether there aren’t deeper problems beyond the recession that has now thankfully passed.

Booker’s contention on this issue, along with the antitrust and noncompete issues, is that there are indeed deeper problems that require deeper changes to put the country back on a path to sustainable higher growth and higher wages.

Certainly, the buyback phenomenon isn’t going anywhere soon without a policy push. February set a one-month record for companies buying their own stock. Analysts at JPMorgan Chase expect total 2018 buybacks to reach $800 billion — way up from $530 billion last year and demolishing 2007’s all-time high that came in a bit below $700 billion.

Booker puts himself firmly on the side of those who are skeptical that low unemployment alone will cure what ails the middle class. “Concentrations of power and wealth,” he says, “are creating a worsening trend that is lowering standards of living for most people.” And with his new bill to curb buybacks, he’s trying to position himself as a leader who pushes back against those trends on multiple fronts.

Sourse: vox.com