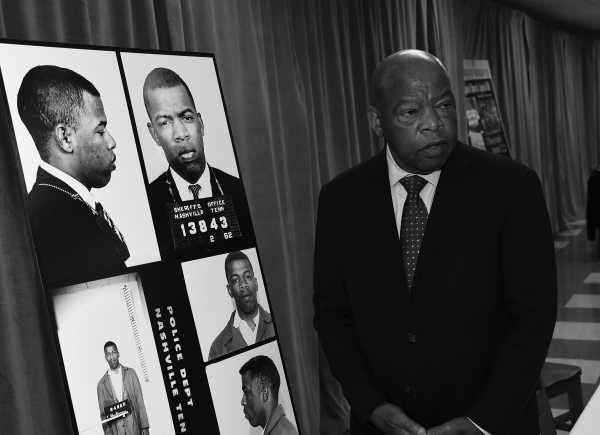

Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, the civil rights leader who served in the House of Representatives for over 30 years and was called “the conscience of the Congress,” died Friday at the age of 80.

The lawmaker — who began his struggle for civil rights at 18 during a lunch counter sit-in in Nashville, Tennessee — announced he had stage 4 pancreatic cancer in December 2019.

At the time, he promised not to let the diagnosis stop him, saying, “I have been in some kind of fight — for freedom, equality, basic human rights — for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now.”

And he did not stop, from making impassioned arguments for President Donald Trump’s impeachment from the floor of the House of Representatives, to taking part in the anti-racism and anti-police brutality protests that have swept the world, visiting Washington, DC’s Black Lives Matter Plaza, and encouraging protesters around the world “to stand up, to speak up, to speak out, to do what I call getting in ‘good trouble.’”

Lewis dedicated his life to improving America through “good trouble”

Getting into good trouble defined Lewis’s life.

Born into a system of strict segregation to sharecroppers near Troy, Alabama, in 1940, Lewis was taught by his parents to avoid interactions with the police, and, as he told the Southern Oral History Program, “you just don’t play around or mess with the law.”

And Lewis’s family would often tell him there was nothing to be done about the racial injustice that permeated every facet of American life in his youth — that it was just something he had to live with.

As Lewis said at the groundbreaking ceremony for Washington, DC’s Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, “I would ask my mother, my father, my grandparents and great grandparents, “Why segregation? Why racial discrimination?” And they would say, “That’s the way it is. Don’t get in trouble. Don’t get in the way.”

Related

John Lewis and the beginning of an era

But Lewis came to believe getting into trouble wasn’t necessarily a bad thing — messing with “the law” was a powerful means of effecting change.

While a student at Nashville’s American Baptist Theological Seminary in the late 1950s, Lewis began to learn about nonviolent organizing. And in November 1959, he took part in his first sit-in, an attempt to force Nashville lunch counters to integrate.

Those Nashville sit-ins continued in 1960, and intensified following the Greensboro sit-ins in February 1960; Lewis described being beaten as he and his fellow students sat quietly, and he was eventually arrested, angering his family.

It was not his last arrest — he and his fellow activists were eventually successful in desegregating Nashville’s lunch counters — and Lewis moved on to other battles throughout the United States, doing work that led to more than 40 arrests.

The arrests did not stop him, nor did being beaten bloody, burnt, and left with broken bones. Instead, Lewis was everywhere he was needed, volunteering to be one of the original Freedom Riders, the activists who staged mobile protests on segregated buses across interstate lines; risking his life to use bathrooms and parks and lunch counters reserved for whites; and traveling across the South to register black voters.

During the 1960s, Lewis helped create, then lead the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and was one of the organizers of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

There, he delivered a fiery address, telling the nation, “We shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy. We must say: ‘Wake up, America. Wake up!’ For we cannot stop, and we will not and cannot be patient.”

Lewis was convinced to tone down the address, removing pointed criticism of the Kennedy administration’s civil rights failings and a promise that black Americans would “march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did.”

Though those words were removed, Lewis made good on that promise — perhaps nowhere more so than in Selma, Alabama, when he led a group of protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965. The protesters had assembled for a march to Montgomery, Alabama, to demand voting rights. They were stopped at the bridge by about 150 members of law enforcement, who ordered them to end their efforts.

Related

John Lewis’s graphic memoir trilogy, March, tells the story of a lifetime of results and actions

The protesters did not. One minute after the order was issued, Lewis and the other demonstrators were attacked — with tear gas, whips, clubs, and barbed wire.

More than 50 people were injured. Lewis suffered a fractured skull, and was beaten as he tried to gather his bearings and struggle to his feet.

He testified about the day — now known as Bloody Sunday — one week later. Images of the beatings, including a photograph of Lewis being hit on the head by an officer, were seen around the world; video of it was broadcast on television. And public pressure created by the brutality led to the federal government enacting the Voting Rights Act, a measure that empowered black voters, and helped bring Lewis into government.

After he was replaced at SNCC by Stokely Carmichael — who advocated for a more confrontational approach to civil rights organizing — Lewis focused on executing the text of the Voting Rights Act, focusing on registering minorities to vote before being called upon by former President Jimmy Carter to lead a federal volunteer agency.

It was these roles that led him into politics, beginning with the city council in Atlanta, and then onward to the US House of Representatives, where he dedicated himself with bringing “good trouble” to Washington.

Lewis was the conscience of Congress

Lewis was regarded as the moral center of Congress.

In recent years, he was seen as an elder statesman who tried to hold his colleagues accountable on issues like gun violence (for instance, he led a congressional sit-in calling for gun reform in 2016) and even impeachment. He told lawmakers in a rousing speech last fall that although he had been slow to back an impeachment inquiry, the time had come to launch one, arguing, “to delay or to do otherwise would betray the foundation of our democracy.”

Lewis’s colleagues praised this activism as a testament to his character; House Speaker Nancy Pelosi wrote on Saturday that the lawmaker was “a titan of the civil rights movement whose goodness, faith and bravery transformed our nation.”

And former President Barack Obama described Lewis as a man who made an “enormous impact on the history of this country” who served “as a beacon in that long journey towards a more perfect union.”

“I first met John when I was in law school, and I told him then that he was one of my heroes,” Obama wrote. “Years later, when I was elected a U.S. Senator, I told him that I stood on his shoulders. When I was elected President of the United States, I hugged him on the inauguration stand before I was sworn in and told him I was only there because of the sacrifices he made.”

Lewis continued making those sacrifices until his death, working to connect the activism of his youth to the issues of the present. He has led yearly commemorations of Bloody Sunday, using those occasions to remind his fellow lawmakers — and Americans in general — that the struggle for voting rights is not over. In fact, with the Supreme Court’s partial negation of the Voting Rights Act and measures like the court’s recent ruling allowing for poll taxes in Florida, the testimony Lewis gave in 1971 before the House Judiciary Committee about black voters remains germane.

“We cannot allow ourselves to be duped into believing that, in these so-called new and changing times, the Voting Rights Act is no longer needed,” Lewis said then. “The figures of unregistered black voters indicate there is still a need for active enforcement of the Voting Rights Act — active enforcement which we have not seen in some time.”

Even in his final days, Lewis did not give up his advocacy. He spent his last weeks visiting the site of anti-racism protests in Washington, DC, and connecting to a new generation of activists.

“It was very moving, very moving to see hundreds of thousands of people from all over America and around the world take to the streets — to speak up, to speak out, to get into what I call ‘good trouble,’” Lewis told Gayle King on CBS This Morning in June. “There will be no turning back.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Sourse: vox.com