Republican and Democratic voters agree that Washington is corrupt.

President Donald Trump’s promises to “drain the swamp” were hugely popular in 2016. And two years later, House Democrats crushed Republicans in a wave election campaigning on cleaning up a “culture of corruption” that had run rampant in the Trump White House.

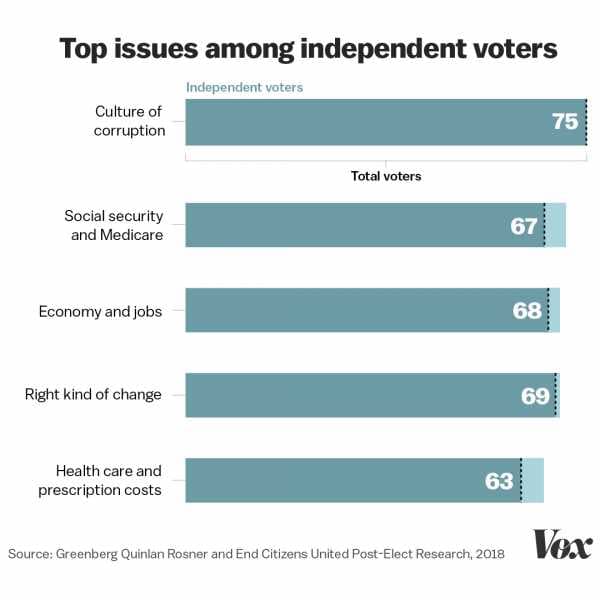

Embracing anti-corruption and pro-democracy reforms are very good politics, and there’s polling from End Citizens United, shared exclusively with Vox, to back that up. The organization’s survey found that 75 percent of 2018 voters in battleground House districts said cracking down on Washington corruption was their top priority, followed by 71 percent who wanted to protect Social Security and Medicare, and 70 percent who listed growing the economy and jobs.

House Democrats are listening; Their first bill of the year is HR 1, a massive anti-corruption bill aimed at stamping out the influence of money in politics, curtailing Washington lobbying, and expanding voting rights.

“We designed it in response to what the public is demanding,” said Rep. John Sarbanes (D-MD), who has been spearheading the legislation.

Campaigning on cleaning up Washington has always been a savvy political move, and Democrats have tried to reform Washington before with little lasting success (albeit with a bill much narrower than HR 1). The exercise demonstrated that while running on the message of ending corruption in Washington will win elections, actually draining the swamp is easier said than done.

Voters want Congress to clean up its act

Democrats flipped many of the battleground districts End Citizens United polled after the election, and many of the candidates who won in those districts ran on an anti-corruption message.

“There’s a new class of members coming to Congress who made reform a critical piece of their message … and that was affirmed” by the election, Sarbanes said.

In some ways, this reinforces a pattern of success that Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump also had during the 2016 presidential election. Sanders and Trump were very different candidates appealing to very different constituencies, but both had the same message: Moneyed establishment politicians in Washington were working for corporations, not the people. Ultimately, that sentiment helped propel Trump to the White House.

Then in 2018, the same sentiment showed itself in conservative districts Democrats flipped by running on an anti-corruption message, among other things. In the End Citizens United poll, an overwhelming number of independent voters — 75 percent — said cleaning up corruption was a very important issue, the most compared to any other issue polled.

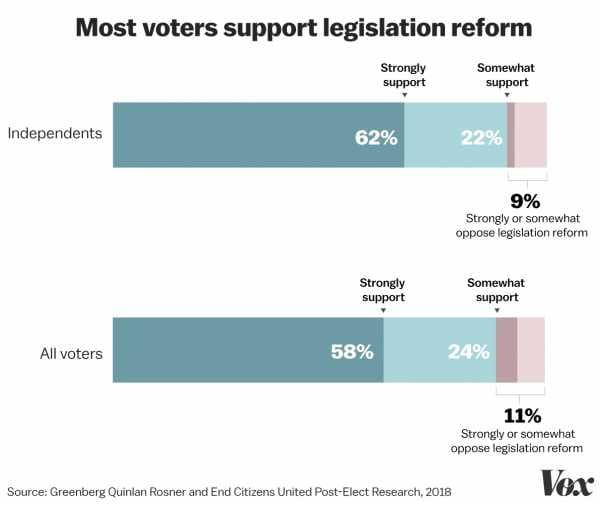

Equally important to the number of voters who thought corruption was a problem was the number who wanted the new Congress to act quickly to pass reform legislation curbing it — 82 percent of all voters and 84 percent of independents said they support a bill of reforms.

The eagerness of independent voters here says something about the bipartisan appeal of anti-corruption reform. Voters of both parties desperately want the government to clean up its act. But if history tells us anything, actually passing meaningful reform is hard.

Democrats have been here before

This isn’t Democrats’ first anti-corruption rodeo.

Back in 2006, Democrats ran on the message of eradicating Washington’s “culture of corruption.” They even coined the phrase “drain the swamp” before Trump started using it — and it helped sweep them into power.

At the time, Democrats and Republicans alike knew they needed to respond to the worst excesses of Washington lobbying, personified by Jack Abramoff, a lobbyist who showered members of Congress with bribes, lavish dinners, and travel to curry influence in Capitol Hill in the late ’90s and early 2000s. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX) resigned over the scandal, and Abramoff and former Rep. Bob Ney (R-OH) both served prison time.

“Once they took over the House, the first item of business on the agenda was the ethics and lobbying reforms,” says Fred Wertheimer, founder and president of pro-democracy nonprofit Democracy 21. “That same approach has been used in this election.”

Democrats seized on the Abramoff scandal during the 2006 election, and Republicans could not ignore it. So in 2007, Congress passed the bipartisan Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, a bill that required more lobbyists to disclose which members of Congress they had donated to and banned gift-giving, meals, and travel.

The bill was championed by a young senator from Illinois named Barack Obama, after Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) asked him to be the face of the legislation.

“That’s the potency of the issue, that Reid tapped a freshman senator that obviously many people thought was going someplace,” said former Reid spokesperson Jim Manley.

The narrow nature of the 2007 reform bill was part of the reason Republicans got on board. It helped cut down on gifts and helped curtail congressional earmarks. But, as Politico wrote in 2016, the bill ultimately didn’t do much to stop the “revolving door” between K Street and Congress that politicians are always talking about slamming shut.

“The opportunities it opened up were lobbying reforms and ethics reforms, and I think it was an effective approach for dealing with those issues,” Wertheimer said. But it isn’t always permanent, he added. “You enact reforms and then people start looking for ways to get around it, and that happens all the time.”

An analysis from Politico showed that out of the 352 people who left Congress in January 2008 (the month the law took effect), nearly half went to work as policy influencers, either directly as lobbyists or as policy advisers, consultants, government relations executives for corporations, or other positions.

Even politicians with intention of cracking down on lobbying have to deal with the reality that Washington, DC, is a very small place. Working on the Hill doesn’t pay as much as working on K Street, and it’s often difficult to find an experienced government staffer who hasn’t worked in the influence industry.

Even though Obama was a champion of reforms as a senator in 2007, he didn’t stamp out corruption. The very same problem came up again when he became president. Obama repeatedly pledged he wouldn’t hire lobbyists to serve in his administration, but then made exceptions for several Cabinet nominees. A Politico investigation ultimately found that Obama had hired more than 70 previously registered lobbyists for key administration jobs.

And on Capitol Hill, the proliferation of money in politics has stayed, albeit in less obvious ways than the Abramoff era.

“In policy-making, when you slam doors shut, very often people find a new door,” said John Lawrence, former chief of staff to incoming House Speaker Nancy Pelosi from 2005 to 2011. “You can’t go to sleep on the Washington lobbying community for eight years and assume they’re not going to figure out activity that’s contrary to what you tried to do in 2007.”

HR 1 is a lot broader than the 2007 bill. That also complicates its chance of passage.

The HR 1 bill Democrats plan to take up as their first priority in the new Congress is far broader than the ethics bill passed in 2007. With Republicans controlling the Senate and the White House, HR 1 will start as a messaging bill and a direct challenge to Republicans to follow suit. With public pressure, advocates hope it will actually be passed in the future.

But action probably won’t happen in 2019 in the upper chamber; Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has already said, “That’s not going to go anywhere.”

House Democrats are fully aware of that, but they are playing the long game with this bill. They will make the case that by not signing onto their reforms, Republicans are part of the problem — and hope that it will boost them in 2020.

“If [McConnell’s] willing to be the face of opposition to real, meaningful democracy reforms the people want to see, that makes it even better policy for Democrats,” Sarbanes told Vox. “To say to the public, from this point forward if you give the gavel to lawmakers who are interested in being accountable to you, this is the kind of change you can expect to see. If you like this, give us a gavel in the Senate, and give us a pen in the White House.”

HR 1 also isn’t just an ethics bill; it will also expand voting rights and tackle campaign finance reform. According to Wertheimer, comparing the two bills is like apples and oranges.

“The impetus in ‘07 was largely some scandals that had occurred, and the need to respond to those,” Sarbanes said. “This time what we’re building [with HR 1] … is much more systemic.”

Sarbanes has a point. The 2007 bill was passed two years before the landmark 2010 Citizens United decision by the US Supreme Court, which opened the door up to a landslide of money in politics. One of the proposals in Sarbanes’s bill is a voluntary public campaign finance system that would reward politicians who forgo corporate PAC money in favor of small donations, making the federal government give them a six-to-one match for every small donation that comes in.

HR 1 also aims to expand voting rights, through automatic voter registration and online voter registration. At the same time, Democrats will try to pass a separate bill that would restore key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, essentially making it harder for states to discriminate against voters of color.

“That is a very big deal. I have not seen anything come this close to the prioritization of this,” said Wendy Weiser, director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “This is I think a real dramatic shot across the bow that I think is a commitment. The Democrats are putting this out there as something they’re going to hold themselves up to.”

Sourse: vox.com