National festivities this week danced on Indian secularism’s grave — and pointed to an existential threat to Indian democracy.

People in Ayodhya watch Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the Ram Mandir consecration ceremony on January 22, 2024. Indranil Aditya/NurPhoto/Getty Images Zack Beauchamp is a senior correspondent at Vox, where he covers ideology and challenges to democracy, both at home and abroad. Before coming to Vox in 2014, he edited TP Ideas, a section of Think Progress devoted to the ideas shaping our political world.

On Monday, tens of millions across India celebrated the opening of the Ram Mandir — a huge new temple to Ram, one of Hinduism’s holiest figures, built in the city of Ayodhya where many Hindus believe he was born.

The celebration in Ayodhya, presided over by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, attracted some of India’s richest and most famous citizens. But in the pomp and circumstance, few dwelled explicitly on the grim origins of Ram Mandir: It was built on the site of an ancient mosque torn down by a Hindu mob in 1992.

Many of the rioters belonged to the RSS, a militant Hindu supremacist group to which Modi has belonged since he was 8 years old. Since ascending to power in 2014, Modi has worked tirelessly to replace India’s secular democracy with a Hindu sectarian state.

The construction of a temple in Ayodhya is the exclamation point on an agenda that has also included revoking the autonomy long provided to the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir, creating new citizenship and immigration rules biased against Muslims, and rewritten textbooks to whitewash Hindu violence against Muslims from Indian history.

Modi has also waged war on the basic institutions of Indian democracy. He and his allies have consolidated control over much of the media, suppressed critical speech on social media, imprisoned protesters, suborned independent government agencies, and even prosecuted Congress party leader Rahul Gandhi on dubious charges.

For many Hindus, the inauguration of the Ram Mandir was a meaningful religious event. But viewed from a political point of view, the event looks like a grim portrait of Modi’s India in miniature: a monument to an exclusive vision of Hinduism built on the ruins of one of the world’s most remarkable secular democracies.

Understanding the temple’s story is thus essential to understanding one of the most important issues of our time: how democracy has come under existential threat in its largest stronghold.

How the Ayodhya temple dispute gave rise to Modi’s India

The dispute over Ayodhya has become a flashpoint in modern Indian politics because it speaks to a fundamental ideological question: Who is India for?

The relevant history here starts in the early 16th century, when a Muslim descendant of Genghis Khan named Babur invaded the Indian subcontinent from his small base in central Asia. Babur’s conquests inaugurated the Mughal Empire, a dynasty that would reign in what is now India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh for generations. At least a remnant of the Mughal state survived until the British seized India in the 19th century.

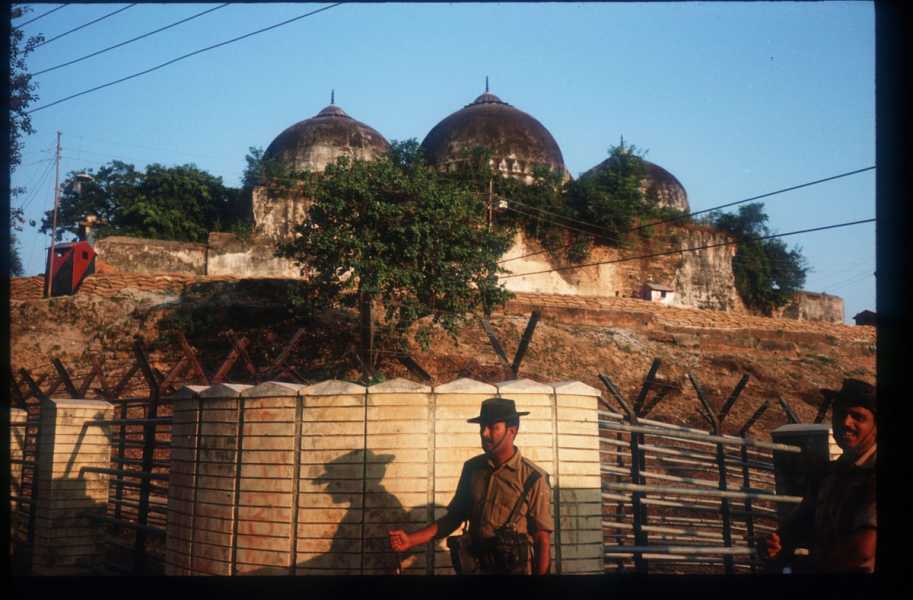

The mosque in Ayodhya was a product of the early Mughal Empire, with some evidence suggesting it was built almost immediately after Babur’s forces conquered Ayodhya in 1529. Called the Babri Masjid — literally “Babur’s Mosque” — it was a testament to the impact the Mughal dynasty and its Muslim rulers had on Indian history and culture.

During the British colonial period, different Indian factions diverged sharply on how to remember the Mughal empire.

For Mahatma Gandhi, who led the mainstream independence movement, the Moghul Empire was a testament to India’s history of religious diversity and pluralism. Gandhi praised the Moghul dynasty, especially its early leadership, for adopting religious toleration as a central state policy. “In those days, they [Hindus and Muslims] were not known to quarrel at all,” he said in 1931, blaming current sectarian tensions on British colonial policy.

But the leadership of the Hindu nationalist RSS organization saw things differently. Focusing in particular on the late Mughal emperor Aurangzeb — who imposed a special tax on non-Muslims and tore down Hindu temples — they argued that the Mughals were more like the British than Gandhi allowed. The Muslim dynasty was not, in their mind, an authentic Indian regime at all; it was just another colonial conquest of an essentially Hindu nation. Muslims could not, and should not, be seen as full and equal members of the polity.

The Babri Masjid swiftly became a major flashpoint for this historical and political dispute. Because Ayodhya was widely seen by Hindus as Ram’s birthplace, the presence of a prominent Mughal mosque there was seen as an affront by Hindu nationalists. In 1949, shortly after independence, a statue of Ram was discovered inside the mosque itself. Hindu nationalists claimed that this was a divine manifestation, proof that the mosque itself was the site where Ram was born.

But according to Hartosh Singh Bal, executive editor of the Indian news magazine The Caravan, the historical record tells a different story.

“Members of a Hindu right-wing organization clambered over the walls, took the idol, [and] placed it there,” Bal told Vox’s Today Explained. “This was the first supposed proof that this [site] was in any way connected to a Hindu monument.”

For years, this manufactured conflict over religion and the Mughal legacy didn’t play a major role in Indian politics. The Congress party, the political descendant of Gandhi’s secular liberal vision for India, dominated Indian politics — winning every single national election for the first 30 years of Indian independence.

But in the 1980s, as the public tired of the Congress party’s domination, Hindu nationalist efforts to stoke tension surrounding the mosque intensified — and caught political fire. The BJP, the political arm of the RSS, made the construction of a Hindu temple on the site of the Babri Masjid a central part of its political agenda. The party, which won just two seats in India’s parliament in 1984’s election, won 85 seats in the 1989 contest.

Indian police guard the Babri Masjid in 1990. Robert Nickelsberg/Liaison

The RSS and BJP kept pressing on the issue, helping organize a series of yatras (pilgrimages) to Ayodhya calling for the mosque’s demolition. These grew huge, unruly, and even violent. In 1992, an out-of-control Hindu nationalist mob armed with hammers and pickaxes stormed the Babri Masjid. They tore it down by hand, horrifying many Indians and setting off religious riots across India that killed thousands.

Andrea Malji, a scholar of Indian religious nationalism at Hawaii Pacific University, describes the Babri Masjid movement as creating a kind of “feedback loop.” By bringing widespread attention to a source of Hindu-Muslim conflict, the movement actually made Hindus and Muslims more afraid of each other — leading to more conflict between the groups and, thus, increasing support among Hindus for Hindu nationalism. This was very good for the BJP’s political fortunes.

“Mobilizing around identity — especially when you’re 80 percent of the country [as Hindus are] is an effective political strategy,” she tells me.

The Ayodhya dispute was not the only reason that, in the coming years, the BJP would displace Congress as the dominant party in Indian politics. Modi’s first national victory, in the 2014 election, owed more to economic issues and Congress’ many corruption scandals than anything else.

But Ayodhya was the crucible in which the BJP’s modern political approach was formed. Modi’s political innovation has been refining this approach, developing a brand of Hindu identity politics with greater appeal to the lower castes than the historically upper caste BJP had previously managed. As time has gone on, he has only gotten more aggressive in pushing his ideological agenda.

Through it all, the Ayodhya issue remained a major priority for both Modi and the BJP. In 2019, just months after Modi’s reelection, India’s Supreme Court ruled that the construction of Ram Mandir on the former site of the Babri Masjid could begin. Its inauguration this week is a declaration of victory for Modi and the BJP on one of their signature issues — one of the most visible in a long line of successes.

Hindu nationalism versus democracy

The Ayodhya dispute helps us understand a deeper connection between the rise of Modi-style populism and the erosion of Indian democracy — that anti-democratic politics is not some kind of bug in BJP rule, but an essential feature.

India’s constitution and founding documents unambiguously declare the country a secular nation of all of its citizens. This universalistic vision permeates Indian law and government; it lies at the heart of the Indian state. India’s founders believed this was essential to making the Indian state a viable democracy: There is no world in which the citizens of such a large and staggeringly diverse country could cooperate together if they weren’t guaranteed certain basic equal rights.

“We must have it clearly in our minds and in the mind of the country that the alliance of religion and politics in the shape of communalism is a most dangerous alliance,” Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, said in a 1948 speech. “The only right way for us to act is to do away with communalism in its political aspect in every shape and form.”

Modi’s Hindu nationalism, by contrast, posits that legitimacy flows not from consent of all the citizens but consent of true people of India. That means Hindus in general, and Hindu nationalists in particular. Because they believe they represent the true nation, Modi and the BJP have no problem steamrolling on the rights of those who disagree with them — including not just Muslims, but also Hindu critics in the press and checks and balances in the Indian state.

“It’s very difficult for me to find compatibility between Hindu nationalism and democracy,” says Aditi Malik, a political scientist at the College of the Holy Cross who studies Indian politics.

There is nothing in theory undemocratic about the construction of a Hindu temple on a recognized holy site, especially when the construction is duly authorized by the legal authorities. But when it’s built on the ruins of a mosque torn down by a Hindu nationalist mob aligned with the ruling government, it sends a signal not just of Hindu joy but of Muslim subordination by any means necessary. Notably, Modi did not, at any point during the ceremony, apologize to India’s Muslims for the violent way in which the road to Ram Mandir was paved.

Devotees queue to get a glimpse of a statue of Ram one day after the consecration ceremony of the Ram Mandir on January 23, 2024, in Ayodhya, India. Ritesh Shukla/Getty Images

Milan Vaishnav, an India expert at the Carnegie Foundation for International Peace, sees this as exemplary of the BJP’s general approach to wielding power. In his view, the party has presided over a gradual breakdown of norms of restraint governing Indian politics — adopting an “ends justify the means” approach to imposing the Hindu nationalist agenda because they believe they speak for the true majority.

“There is this feeling that, because this government is democratically elected, whatever they do has a democratic imprimatur,” he says.

Modi’s war on the free press — which has included friendly oligarchs buying up independent media outlets, siccing auditors on critical media outlets, and even imprisoning reporters on terrorism charges — is a case in point.

Seeking to force the media to tow a friendly line is undemocratic under any definition, even if the policies are authorized by a legislative majority. But the BJP believes that it, and it alone, speaks on behalf of the Hindu nation — and that critics in the press have no more right to challenge them than Muslims do.

There is every reason to believe that India will continue following this anti-democratic path in the years to come.

Across India, Ram Mandir’s inauguration was widely seen as the beginning of Modi’s reelection campaign. With elections scheduled to begin sometime in the mid-to-late spring, Modi is previewing a campaign focused on his appeal as an almost godlike champion for Hindus.

“[The temple inauguration] bolsters an image of Mr. Modi as the champion of Indians abroad and Hindus at home; as someone who keeps his promises,” Manjari Chatterjee Miller, a senior fellow studying South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, tells me. “Expect much much more of this as election season gets underway.”

The consensus among India watchers is that Modi will win comfortably. The BJP is coming off three victories in December local elections, and the prime minister himself has an approval rating somewhere in the 70s. Whatever one’s opinion of Modi’s Hindu nationalism, there’s no doubt that it’s genuinely popular with hundreds of millions of Indians.

In evaluating India, we have to hold two thoughts in our heads at the same time. First, Modi and his agenda is genuinely popular with the Hindu majority. Second, this popularity has given him room to pursue an ideological agenda that imperils the long-term viability of Indian democracy.

When Modi said in his speech at Ayodhya that the day marks “the beginning of a new era,” this might very well be true. India could be at the beginning of a long illiberal night — one its democracy may not be able to survive.

Sourse: vox.com