CNN is suing the White House for revoking the press credentials of White House correspondent Jim Acosta over a testy exchange between Acosta and President Donald Trump at a press conference the day after the midterm elections.

Press secretary Sarah Sanders explained the decision by accusing Acosta of “placing his hands” on a White House aide who tried to physically remove a microphone from Acosta. Sanders tweeted a doctored video from Infowars that both she and Trump have somewhat bizarrely argued was not doctored and supports Sanders’s version of events.

Many people — including a large share of professional political journalists — watched the actual events play out live on television and confirm that’s not what happened.

CNN, in its lawsuit, argues that since none of what the White House said actually happened, the whole thing is bogus and Acosta should have his press pass restored.

The network is positioning itself as not just standing up for its employee and its own business interests but acting in the best traditions of American journalism as a cornerstone of a free society that holds the powerful accountable. Certainly there’s some of that happening in CNN’s suit, and the White House’s relentlessly dishonesty about this sequence of events (and, indeed, its relentless dishonesty about everything) is antithetical to those best traditions of our country.

But while nobody thinks Acosta assaulted a White House staffer, plenty of people did find his conduct to be inappropriate grandstanding. And this face-off between Trump and CNN is just one flurry in a larger war between Trump and the mainstream press that has an element of phoniness to it — perhaps nowhere more so than on television. After all, while there is a real conflict here, there is also a real confluence of interests. Trump is good for CNN’s business, and CNN is a good foil for Trump’s politics.

Acosta and Trump — the facts

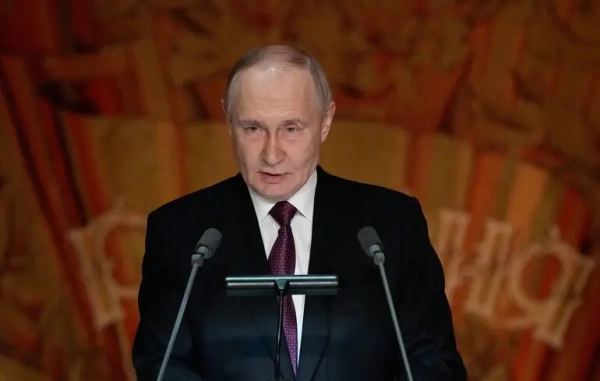

Trump followed up Democrats’ midterm elections win with a bizarre press conference in which he proclaimed victory and said a bunch of stuff that isn’t true, including that he has a secret plan to resolve the political dispute about abortion rights.

One of several bizarre interludes during the press conference was this back-and-forth between Trump and Acosta, which Vox’s Aaron Rupar described at the time:

Trump later renewed his attack on Acosta, saying “when you report fake news, which CNN does a lot, you are the enemy of the people.” He also repeatedly told April Ryan to “sit down” and accused Yamiche Alcindor of asking a “racist question” when she asked about white nationalists’ enthusiasm for his rhetoric.

This particular weird incident with Acosta and the staffer might be no more remembered than a dozen other bizarre moments from that press conference. (Trump openly mocked losing House Republican candidates, misstated the tipping point states in the Electoral College, threatened politically motivated investigations of House Democrats, blamed “Obama’s regime” for Russian annexation of Crimea, claimed to be unable to understand foreign journalists’ accents, wildly mischaracterized both DACA and the Affordable Care Act, and said some stuff about China that was so incoherent, it’s hard to even call it lying.)

But Sanders followed up by slandering Acosta on Twitter with the charge of “placing his hands on a young woman just trying to do her job as a White House intern” and explaining that his pass to the briefing room had been revoked.

That is not what happened.

But about 90 minutes later, Paul Watson of the notorious conspiracy site Infowars tweeted a video of the incident that had been doctored to make it look like Acosta karate-chopped the intern’s arm.

Within an hour, Sanders herself was tweeting Watson’s doctored video, writing “we will not tolerate the inappropriate behavior clearly documented in this video.”

So the White House position is that Acosta should be banned from the briefing room for doing something he didn’t do, and they have produced fake evidence to support their contention.

CNN, rather naturally, is pushing back on this, using both legal and PR channels.

CNN’s legal case against Trump

On the legal merits, CNN appears to have a fairly strong case.

As David Lurie explained for Slate before the suit was filed, there is a broadly parallel legal precedent from the Vietnam era that seems to apply in a fairly straightforward manner to the Acosta case:

Three factors prevent CNN’s suit from being an entirely open-and-shut case:

- The Sherrill case arose at the low ebb of US partisan polarization and did not have much partisan content. The denials of a press pass occurred under both a Democratic and a Republican administration and the final litigation occurred when yet another administration was in office.

- The Trump administration claims, factually, that it has video evidence of Acosta attacking a White House intern and that this offers a non-pretextual reason to deny him the pass. This is not actually true, but it’s conceivable that the administration will get someone from the Secret Service to say they share Sanders’s interpretation of the video, thus presenting a novel pattern of facts.

- The Sherrill case didn’t ultimately go to the Supreme Court, so the precedent isn’t entirely definitive. The judiciary has, on the whole, become more conservative since the 1970s, and it’s always possible that judges will simply rule differently.

On the other hand, the larger context is almost certainly that the White House doesn’t particularly care whether they win this case. Acosta returning to the briefing room doesn’t damage them in any concrete way, and while nobody in journalism is happy about this treatment of CNN’s correspondent, most feel that Trump regards the controversy as a welcome distraction from the installation of a wildly underqualified acting attorney general and other matters.

Trump’s mutually beneficial war with CNN

Broadly speaking, both Trump and CNN enjoy the narrative that Trump is at war with CNN. Back in July 2017, Trump rather egregiously courted CNN-related controversy by tweeting a fan meme of himself defeating CNN in a pro wrestling context.

The world of wrestling, not entirely coincidentally, gave us the concept of “kayfabe” — the elaborate apparatus of feuds and backstory that everyone involved in the sport is supposed to pretend are real in order to make things more entertaining for everyone.

CNN, at the same time, has wielded Trump’s criticisms of the network as a marketing tool — adopting Kellyanne Conway’s infamous “alternative facts” gaffe for its own branding as the One True Source of Real Facts.

The truth of the matter, however, is that Conway is a frequent guest on CNN programs.

It’s true that CNN hosts typically give her a hard time about the controversy of the day, and make various faces indicating disgust or outrage at her dishonesty. But they don’t respond to that disgust or outrage by doing something sensible like declining to book her in the future.

Generally speaking, if you are interested in informing the public, you don’t dedicate lots of airtime to letting a deeply dishonest person speak and then make weird faces as if you’re surprised to discover she’s a liar. You just go book someone more honest instead.

By the same token, if the Trump administration genuinely believed CNN was broadcasting “fake news,” it wouldn’t send its people to the network.

Just as a group of people who were actually embroiled in the set of convoluted feuds portrayed by the WWE wouldn’t be competing against each other on a regular circuit of wrestling matches, two groups who had the kind of disdain for each other that CNN and the White House claim to have wouldn’t have so much mutual engagement.

The truth is that Trump is good for ratings (which is why CNN had extensive Trump coverage way back when even Fox was a little skeptical of his candidacy), and the semi-fake feud with CNN is something Trump is more comfortable discussing than actual policy issues. His substantive command of them is weak, and the GOP agenda he’s embraced is mostly unpopular.

The media is a convenient foil for Trump

Sparring with the press is useful for Trump in part because it tends to fuel media coverage of him, which to an extent he sees as its own reward. As far back as his 1980s book The Art of the Deal, Trump has frequently espoused a “no such thing as bad publicity” theory of media relations, and that tactic served him extremely well in the Republican presidential primary, when press attention was a genuinely scarce resource amid a crowded field.

It’s doubtful that the same approach was genuinely advantageous to him during the general election against Hillary Clinton, but the fact is that he won when almost everyone (myself included) expected him to lose, so it’s hardly surprising that Trump is inclined to stick with the tactics that brought him to where he is today.

But more broadly, to cast the press as the real “opposition party” in America — as Trump has — offers some meaningful tactical advantages. Trump, in an unusual way, won the 2016 presidential election without being popular. Not only did he win fewer votes than Hillary Clinton on Election Day, but his favorability rating was lower than that of the losing candidates from the 2012, 2008, 2004, and 2000 presidential elections.

The nonpartisan press can (and does) report facts that are unflattering to Trump. But a lack of unflattering facts or a failure by the public to appreciate their existence has never been the foundation of Trump’s political success. And the press isn’t going to do the work of an actual opposition party, which is to formulate a political alternative that an adequate number of people find to be sufficiently inspiring to go out and vote for.

That’s the job of the Democratic Party, an institution that’s had considerable trouble attracting press attention to its own message and ideas ever since Trump exploded on the scene. And keeping the media focused on a self-referential feud between Trump and the media is a way to maintain his preferred approach of trying to suck up all the oxygen in the room.

Meanwhile, what matters to Trump isn’t any actual crushing of the media but simply driving the narrative in his core followers’ heads that the media is at war with him. With that pretense in place, critical coverage and unflattering facts can be dismissed even as Trump selectively courts the press to inject his own preferred ideas into the mainstream.

Sourse: vox.com