It’s going to happen again. There will be another mass shooting in America.

It’s tragic to even write those words, but this is the clear pattern I’ve seen since I began covering mass shootings for Vox in 2014: A horrific tragedy happens. There are calls for action. Maybe something gets introduced in Congress. The debate goes back and forth for a bit. Then people move on — usually after a week or two. And so there’s eventually another shooting.

As a reporter, I have become eerily attuned to this horrible American ritual. I do the same thing every single time we get news of a mass shooting: verify reports, write a “what we know” article, and then begin to update our old pieces on guns. I do this almost instinctively at this point — and that terrifies me. No one should get used to this.

There are signs that the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, which killed 17 people, could have a different outcome. With the March for Our Lives and similar demonstrations across the country on Saturday, students with highly sympathetic stories are speaking up. The sense of outrage this time seems sustained — and that may buck the trend.

“Politicians who sit in their gilded House and Senate seats funded by the NRA telling us nothing could have ever been done to prevent this, we call BS,” Emma Gonzales, a student survivor, said in a speech at a February gun control rally that went viral. “They say that tougher gun laws do not decrease gun violence. We call BS. They say a good guy with a gun stops a bad guy with a gun. We call BS. They say guns are just tools like knives and are as dangerous as cars. We call BS. … They say that no laws could have been able to prevent the hundreds of senseless tragedies that have occurred. We call BS.”

But at least so far, nothing has changed. Congress has passed no significant gun reforms — and it still doesn’t look likely to do so, even as people take to the streets.

This is typical. The federal government did nothing after 6- and 7-year-olds were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, where a gunman killed 20 children, six adults, and himself in 2012. Since then, there have been more than 1,600 mass shootings, killing more than 1,800 people and wounding more than 6,400. Many of these events led to protests and calls for actions, but Congress refused to budge every time.

As I see it, the core issue is that America as a whole refuses to even admit it has a serious problem with guns and gun violence. And more than that, lawmakers continue acting like the solutions are some sort of mystery, as if there aren’t years of research and experiences in other countries that show restrictions on firearms can save lives.

Consider President Donald Trump’s initial speech responding to the Florida shooting: His only mention of guns was a vague reference to “gunfire” as he described what happened. He never even brought up gun control or anything related to that debate, instead vaguely promising to work “with state and local leaders to help secure our schools and tackle the difficult issue of mental health.”

This is America’s elected leader — and he essentially, based on his first public response, ignored what the real problem is. And although the White House has come around to bipartisan proposals to very slightly improve background checks and ban bump stocks, the compromises amount to fairly small changes to America’s weak gun laws.

In my coverage of these shootings, I’ve always focused on solutions through studies and policy ideas that would tamp down on the number of shootings. The good news is there are real solutions out there.

But America can’t get to those solutions until it admits it has a gun problem and confronts the reality of what it would mean to seriously address it.

1) America has a unique gun violence problem

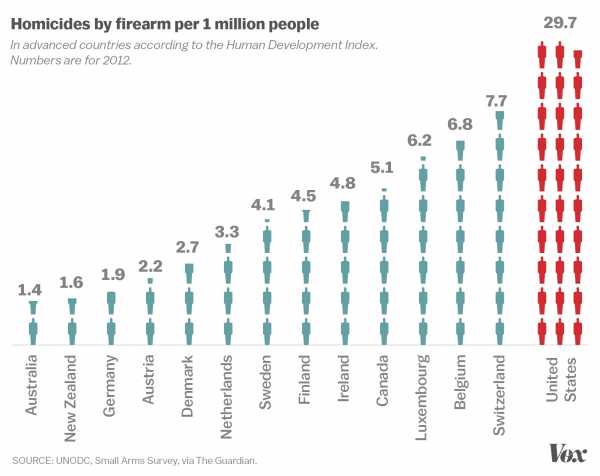

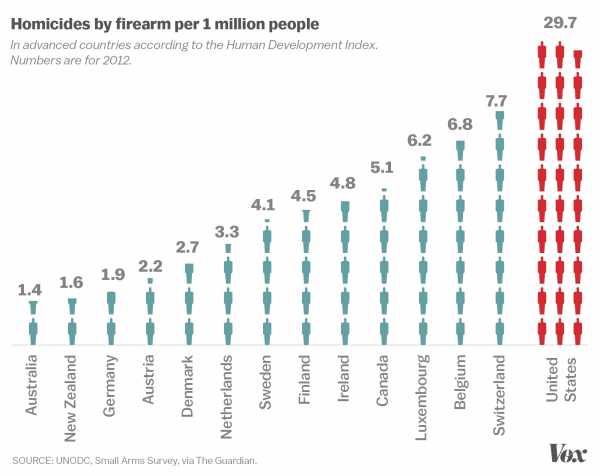

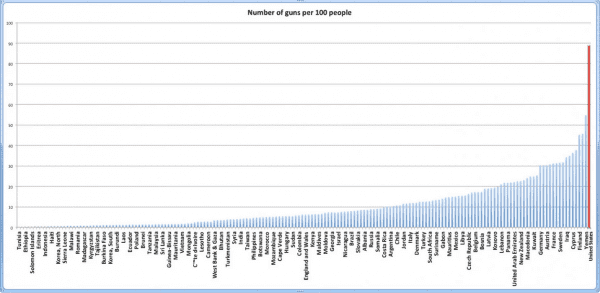

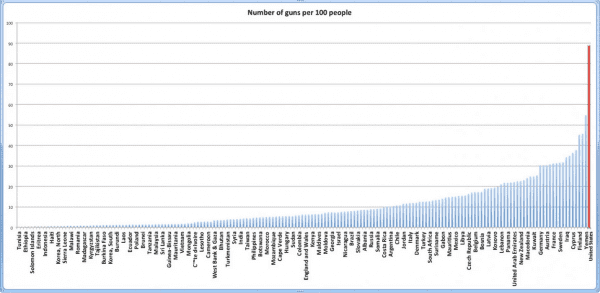

The US is unique in two key — and related — ways when it comes to guns: It has way more gun deaths than other developed nations, and it has far higher levels of gun ownership than any other country in the world.

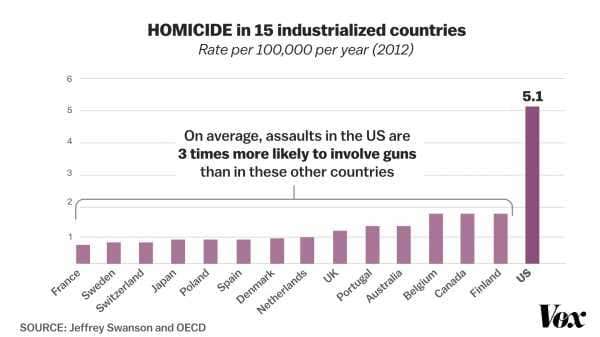

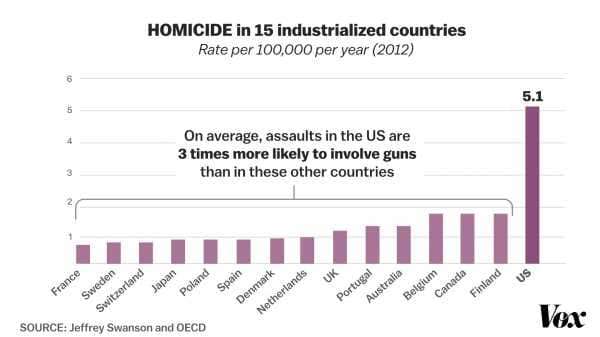

The US has nearly six times the gun homicide rate of Canada, more than seven times that of Sweden, and nearly 16 times that of Germany, according to United Nations data compiled by the Guardian. (These gun deaths are a big reason America has a much higher overall homicide rate, which includes non-gun deaths, than other developed nations.)

Mass shootings actually make up a small fraction of America’s gun deaths, constituting less than 2 percent of such deaths in 2013. But America does see a lot of these horrific events: According to CNN, “The US makes up less than 5% of the world’s population, but holds 31% of global mass shooters.”

The US also has by far the highest number of privately owned guns in the world. Estimated in 2007, the number of civilian-owned firearms in the US was 88.8 guns per 100 people, meaning there was almost one privately owned gun per American and more than one per American adult. The world’s second-ranked country was Yemen, a quasi-failed state torn by civil war, where there were 54.8 guns per 100 people.

Another way of looking at that: Americans make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population yet own roughly 42 percent of all the world’s privately held firearms.

These two facts — on gun deaths and firearm ownership — are related. The research, compiled by the Harvard School of Public Health’s Injury Control Research Center, is pretty clear: After controlling for variables such as socioeconomic factors and other crime, places with more guns have more gun deaths.

“Within the United States, a wide array of empirical evidence indicates that more guns in a community leads to more homicide,” David Hemenway, the Injury Control Research Center’s director, wrote in Private Guns, Public Health.

For example, a 2013 study, led by a Boston University School of Public Health researcher, found that, after controlling for multiple variables, a 1 percent increase in gun ownership correlated with a roughly 0.9 percent rise in the firearm homicide rate at the state level.

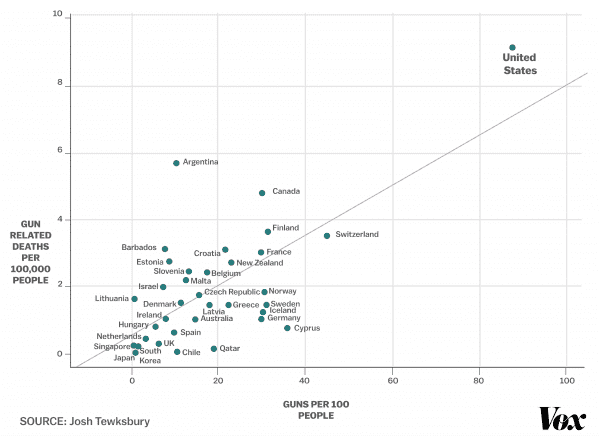

This chart, based on data compiled by researcher Josh Tewksbury, shows the correlation between the number of guns and gun deaths among wealthier nations:

Guns are not the only contributor to violence. (Other factors include, for example, poverty, urbanization, and alcohol consumption.) But when researchers control for other confounding variables, they have found time and time again that America’s high levels of gun ownership are a major reason the US is so much worse in terms of gun violence than its developed peers.

2) The problem is guns, not mental illness

Supporters of gun rights look at America’s high levels of gun violence and argue that guns are not the problem. They point to other issues, from violence in video games and movies to the supposed breakdown of the traditional family.

Most recently, they’ve focused particularly on mental health. This is the only policy issue that Trump mentioned in his speech following the Florida shooting.

But as Dylan Matthews explained for Vox, people with mental illnesses are more likely to be victims, not perpetrators, of violence. And Michael Stone, a psychiatrist at Columbia University who maintains a database of mass shooters, wrote in a 2015 analysis that only 52 out of the 235 killers in the database, or about 22 percent, had mental illnesses. “The mentally ill should not bear the burden of being regarded as the ‘chief’ perpetrators of mass murder,” he concluded. Other research has backed this up.

The problem, instead, is guns — and America’s abundance of them.

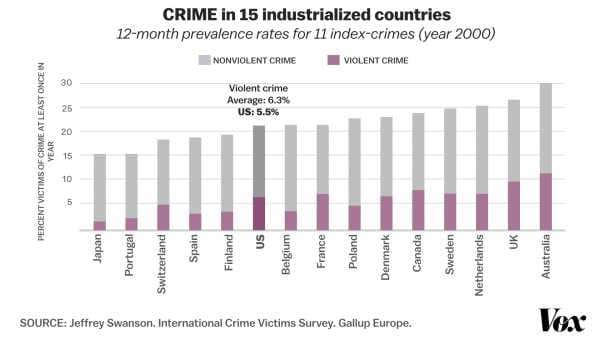

As a breakthrough analysis by UC Berkeley’s Franklin Zimring and Gordon Hawkins in 1999 found, it’s not even that the US has more crime than other developed countries. This chart, based on data from Jeffrey Swanson at Duke University, shows that the US is not an outlier when it comes to overall crime:

Instead, the US appears to have more lethal violence — and that’s driven in large part by the prevalence of guns.

”A series of specific comparisons of the death rates from property crime and assault in New York City and London show how enormous differences in death risk can be explained even while general patterns are similar,” Zimring and Hawkins wrote. “A preference for crimes of personal force and the willingness and ability to use guns in robbery make similar levels of property crime 54 times as deadly in New York City as in London.”

This is in many ways intuitive: People of every country get into arguments and fights with friends, family, and peers. But in the US, it’s much more likely that someone will get angry at an argument and be able to pull out a gun and kill someone.

3) The research shows that gun control works

The research also suggests that gun control can work. A 2016 review of 130 studies in 10 countries, published in Epidemiologic Reviews, found that new legal restrictions on owning and purchasing guns tended to be followed by a drop in gun violence — a strong indicator that restricting access to firearms can save lives.

Consider Australia’s example.

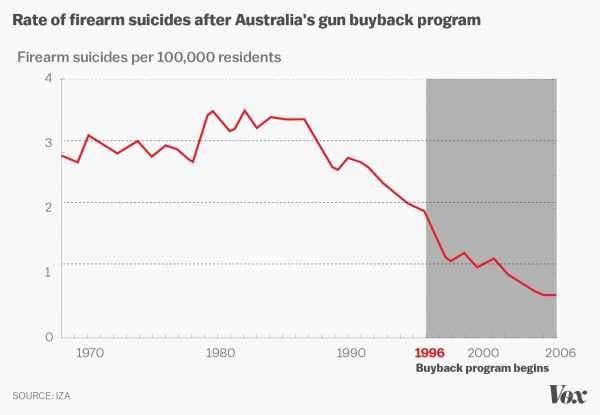

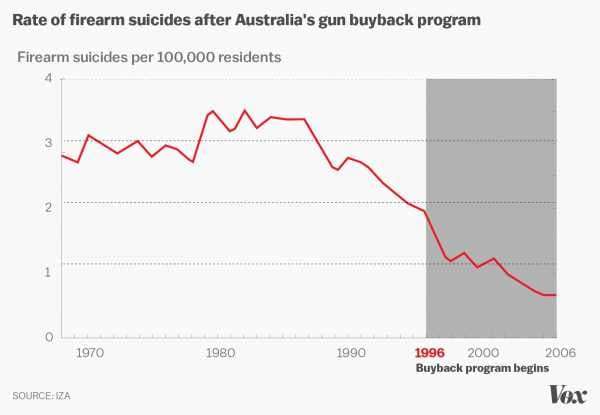

In 1996, a 28-year-old man walked into a cafe in Port Arthur, Australia, ate lunch, pulled a semiautomatic rifle out of his bag, and opened fire on the crowd, killing 35 people and wounding 23 more. It was the worst mass shooting in Australia’s history.

Australian lawmakers responded with legislation that, among other provisions, banned certain types of firearms, such as automatic and semiautomatic rifles and shotguns. The Australian government confiscated 650,000 of these guns through a mandatory buyback program, in which it purchased firearms from gun owners. It established a registry of all guns owned in the country and required a permit for all new firearm purchases. (This is much further than bills typically proposed in the US, which almost never make a serious attempt to immediately reduce the number of guns in the country.)

Australia’s firearm homicide rate dropped by about 42 percent in the seven years after the law passed, and its firearm suicide rate fell by 57 percent, according to a review of the evidence by Harvard researchers.

It’s difficult to know for sure how much of the drop in homicides and suicides was caused specifically by the gun buyback program and other legal changes. Australia’s gun deaths, for one, were already declining before the law passed. But researchers David Hemenway and Mary Vriniotis argue that the gun buyback program very likely played a role: “First, the drop in firearm deaths was largest among the type of firearms most affected by the buyback. Second, firearm deaths in states with higher buyback rates per capita fell proportionately more than in states with lower buyback rates.”

One study of the program, by Australian researchers, found that buying back 3,500 guns per 100,000 people correlated with up to a 50 percent drop in firearm homicides and a 74 percent drop in gun suicides. As Matthews explained, the drop in homicides wasn’t statistically significant because Australia already had a pretty low number of murders. But the drop in suicides most definitely was — and the results are striking.

One other fact, noted by Hemenway and Vriniotis in 2011: “While 13 gun massacres (the killing of 4 or more people at one time) occurred in Australia in the 18 years before the [Australia gun control law], resulting in more than one hundred deaths, in the 14 following years (and up to the present), there were no gun massacres.”

4) State and local actions are not enough

A common counterpoint to the evidence on gun control: If it works so well, why does Chicago have so much gun violence despite having some of the strictest gun policies in the US?

White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders made this argument after the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting: “I think if you look to Chicago, where you had over 4,000 victims of gun-related crimes last year, they have the strictest gun laws in the country. That certainly hasn’t helped there.”

It’s true that Chicago has fairly strict gun laws (although not the strictest). And it’s true that the city has fairly high levels of gun violence (although also not the worst in the US).

This doesn’t, however, expose the failure of gun control altogether, but rather the limits of leaving gun policies to a patchwork of local and state laws. The basic problem: If a city or state passes strict gun control measures, people can simply cross a border to buy guns in a jurisdiction with laxer laws.

Chicago, for example, requires a Firearm Owners Identification card, a background check, a three-day waiting period, and documentation for all firearm sales. But Indiana, across the border, doesn’t require any of this for purchases between two private individuals (including those at gun shows and those who meet through the internet), allowing even someone with a criminal record to buy a firearm without passing a background check or submitting paperwork recording the sale.

So someone from Chicago can drive across the border — to Indiana or to other places with lax gun laws — and buy a gun without any of the big legal hurdles he would face at home. Then that person can resell or give guns to others in Chicago, or keep them, leaving no paper trail behind. (This is illegal trafficking under federal law, but Indiana’s lax laws and enforcement — particularly the lack of a paper trail — make it virtually impossible to catch someone until a gun is used in a crime.)

The result: According to a 2014 report from the Chicago Police Department, nearly 60 percent of the guns in crime scenes that were recovered and traced between 2009 and 2013 came from outside the state. About 19 percent came from Indiana — making it the most common state of origin for guns besides Illinois.

This isn’t exclusive to Chicago. A 2016 report from the New York State Office of the Attorney General found that 74 percent of guns used in crimes in New York between 2010 and 2015 came from states with lax gun laws. (The gun trafficking chain from Southern states with weak gun laws to New York is so well-known it even has a name: “the Iron Pipeline.”) And another 2016 report from the US Government Accountability Office found that most of the guns — as many as 70 percent — used in crimes in Mexico, which has strict gun laws, can be traced back to the US, which has generally weaker gun laws.

That doesn’t mean the stricter gun laws in Chicago, New York, or any other jurisdiction have no effect, but it does limit how far these local and state measures can go, since the root of the problem lies in other places’ laws. The only way the pipeline could be stopped would be if all states individually strengthened their gun laws at once — or, more realistically, if the federal government passed a law that enforces stricter rules across the US.

5) America probably needs to go further than anyone wants to admit

America’s attention to gun control often focuses on a few specific measures: universal background checks, restrictions on people with mental illnesses buying firearms, and an assault weapons ban, for example. It is rare that American politicians, even on the left, go much further than that. Something like Australia’s law — which amounts to a confiscation program — is never seriously considered.

As Dylan Matthews previously explained, this is a big issue. The US’s gun problem is so dire that it arguably needs solutions that go way further than what we typically see in mainstream proposals — at least, if the US ever hopes to get down to European levels of gun violence.

If the fundamental problem is that America has far too many guns, then policies need to cut the number of guns in circulation right now to seriously reduce the number of gun deaths. Background checks and other restrictions on who can buy a gun can’t achieve that in the short term. What America likely needs, then, is something more like Australia’s mandatory buyback program — essentially, a gun confiscation scheme — paired with a serious ban on specific firearms (including, potentially, all semiautomatic weapons).

But no one in Congress is seriously proposing something that sweeping. The Manchin-Toomey bill, the only gun legislation in Congress after Sandy Hook that came close to becoming law, didn’t even establish universal background checks. Recent proposals have been even milder, taking small steps like banning bump stocks or slightly improving the existing system for background checks.

Part of the holdup is the Second Amendment. While there is reasonable scholarly debate about whether the Second Amendment actually protects all Americans’ individual right to bear arms and prohibits stricter forms of gun control, the reality is the Supreme Court and US lawmakers — backed by the powerful gun lobby, particularly the NRA — widely agree that the Second Amendment does put barriers on how far restrictions can go. That would likely rule out anything like the Australian policy response short of a court reinterpretation or a repeal of the Second Amendment, neither of which seems likely.

So the US, for political, cultural, and legal reasons, seems to be unable to take the action that it really needs.

None of that is to say that milder measures are useless. Connecticut’s law requiring handgun purchasers to first pass a background check and obtain a license, for example, was followed by a 40 percent drop in gun homicides and a 15 percent reduction in gun suicides. Similar results — in the reverse — were reported in Missouri when it repealed its own permit-to-purchase law. It’s difficult to separate these changes from long-term trends (especially since gun homicides have generally been on the decline for decades now), but a review of the evidence by RAND linked milder gun control measures, including background checks, to reduced injuries and deaths — and that means these measures likely saved lives.

There are also some evidence-based policies that could help outside the realm of gun control, including more stringent regulations and taxes on alcohol, changes in policing, and behavioral intervention programs.

But if America wants to get to the levels of gun deaths that its European peers report, it will likely need to go much, much further on guns in particular.

Sourse: vox.com