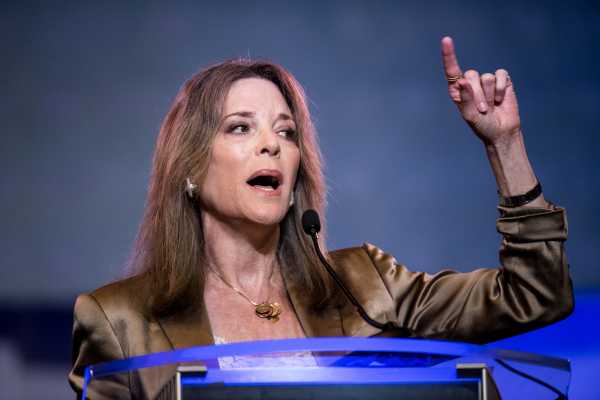

It’s tempting to dismiss Marianne Williamson, who arrived on the Democratic debate stage in late June to declare, “I’m going to harness love for political purposes.” But many people are completely serious about her.

“She knows how to capture the hearts of people,” said Jacqueline Moore, one of Williamson’s supporters from Florida. “We don’t need a political mechanic, we need a political visionary.”

Moore, 69, retired from AT&T in 2001 and is now a civility and human potential educator, where she focuses on, as she puts it, “illuminating human potential.” She first came across Williamson in the 1990s, during what she considers a spiritual awakening in her life. Moore sees Williamson as a woman she can aspire to be and relate to. “I call her a modern-day prophet, because of the way she is able to receive and transmit truths,” she said.

During our 30-minute phone conversation in early July, Moore often referred to the time before she got into spirituality as the era before she “woke up,” and she talked about the “ages and stages” of life. Would she be interested in other 2020 candidates? Maybe. She saw Williamson had done a campaign call with Andrew Yang, but she was turned off by the “fight” rhetoric of many of the others. But right now, she sees herself as a soldier for Marianne. “I don’t just like the vision. I trust the her that is behind the vision,” she said.

Williamson’s words speak to those who back her, both ironically and unironically, though they recognize it can all sound a little “woo-woo” and “airy fairy.” But Williamson had enough support to land on the debate stage in the first place, and after it, she is nothing short of a phenom. The author and spiritual leader was the most-searched candidate on Google and became the subject of endless memes.

Josh Wechsler, a 34-year-old musical theater performance educator in Austin, Texas, said there are plenty of candidates that he thinks are wonderful and would be happy to support. But in Williamson, he sees an “inspirer-in-chief” whose candidacy has gotten him and others in the spiritual community, which has largely been inactive in politics, interested. “We thought we were above it,” he told me. “Her platform has been: If anybody needs to be involved, it’s people who have a social conscious, it’s people who care about unity and inclusion and making the world a better place.”

Wechsler discovered Williamson as a teen, while he was grappling with coming out, and she “probably saved my life,” he said. (When I pointed out we were about the same age and asked how he’d even found her back then, he reminded me that at the time things were pretty “witchy.” Remembering how into Buffy and Charmed I was, it rang true.) Can some of the things Williamson said on the debate stage come off as a little odd, like her saying we don’t need plans but instead have to address underlying problems? Not if you’ve been following Williamson, who teaches that a problem on the surface is just a reflection of something deeper. Her longtime followers understand her and know what she means.

I spoke with a dozen Williamson supporters — not those who picked her off a list of 24 Democratic presidential candidates, but those who have been buying her books, following her teachings, and engaging with her for years. I learned she occupies a space in America that is something between the serious and the fringe, between the religious and the non-religious, the political and the non-political, and speaks to a lot of people who have been looking for a message like hers. She berated her fellow candidates on the debate stage, pointing out Donald Trump won without any policy plans — and, honestly, her point is well taken.

Sure, Williamson doesn’t have any experience in elected office (though she did make an unsuccessful run for Congress in 2014), but neither did Trump.

“Yesterday she was not known by a lot of people, today they search for her, and tomorrow they will fall in love with her,” said Laura Guzman-Rodriguez, a 54-year-old Texas woman.

A Course in Miracles, but for America

Williamson, 67, first gained real national public prominence in 1992, when she published her first book, A Return to Love, and appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s show to talk about it. The book offered up her interpretation of A Course in Miracles.

As Vox explained earlier this year, A Course in Miracles, often referred to just as the Course, is a “massive three-volume religious work that teaches that the only real thing in the world is God’s love, and surrendering to God’s plan can lead to inner-peace and real-life miracles” published in the mid-1970s. It was published at a time when modern life seemed to be breaking with the dominance of religion and came on the tail of massive social change, such as second-wave feminism and the civil rights movement. The Course employs the language of Christianity, and its original author, medical psychologist Helen Schucman, said that Jesus had dictated it to her. Its adherents consider it to be a secular text and say the terminology was basically a way to make it more accessible.

A Course in Miracles resonated with Williamson, and she decided to bring it to others with A Return to Love. The book became a New York Times bestseller.

Linda Nellis, a 38-year-old yoga instructor and executive administrator from California, told me that Williamson’s book was her “own kind of Bible,” including during the Trump presidency.

Many of the Williamson supporters with whom I spoke were students of A Course in Miracles and had attended meetings and done readings on it consistently over the years. They’re not an anomaly. A growing swath of the American electorate describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” and spiritual practices, such as yoga, meditation, and mindfulness, are now part of mainstream culture.

On the debate stage, much of what Williamson was talking about — coming from a place of love, addressing the underlying causes of problems instead of plans, focusing on children — is in line with teachings from A Course on Miracles and, more broadly, concepts Williamson has been lecturing about for years.

“The same principle that transforms individual lives is the same principle that will transform our nation,” said Susie Owens, a 50-year-old nurse from Long Island.

It’s clear that a lot of the people who follow her really do feel that she’s transformed their lives. After the death of one of her children, Owens, for example, found Williamson and attended her weekly lectures in New York City. She texted me a picture of herself asking Williamson a question at one of them.

Others told me similar stories, that they found Williamson during difficult times in their lives and she helped them to move forward. They think she can also help the country. Pre-Marianne for president, they weren’t paying that much attention to politics, but now they are. And, like Owens, they sent follow-up content — a lot of it, including videos, news articles, blog posts, and speeches. They wanted me to know who Marianne is, from their perspective.

In Marianne we trust

Williamson’s supporters think Trump has broken the country and Williamson is the answer for healing it. She is like Trump in connecting with a feeling among people, but she is also the antithesis of Trump. He is fear; she is love.

“I don’t know why that sounds so crazy to people,” Nellis said, “because Trump won on a platform of fear, and Obama won on a platform of hope.”

When I asked Wechsler what he thought Williamson would do as president, he joked that “our tweets would get a lot more inspirational,” but on a more serious note, said that having someone in the White House “with their focus on the moral and ethical sanity of the American people” would be a good place to start.

“Her gift is leadership,” said Sara Eubank, a 66-year-old former Utah state representative who says Williamson inspired her own political ambitions in the 1990s. “She knows how to help people look at the issues from various perspectives and then work together and find solutions.”

It is worth noting that some of Williamson’s teachings and positions, namely on health and science, have been controversial. As Ashley Reese at Jezebel notes, Williamson has been criticized for having questionable advice on weight loss, pushing against the use of medication in some cases of mental illness, and at times seemingly suggesting sickness can be addressed through spirituality instead of medical treatment.

On the campaign trail, her comments about vaccines raised eyebrows — she called mandatory vaccines “draconian” and “Orwellian” at a campaign stop in New Hampshire in June. She later walked the comments back, sort of, and said that “many vaccines are important and save lives,” but she understands the skepticism around drugs “rushed to market by Big Pharma.”

One of Williamson’s supporters in an email told me she was “disappointed” that Williamson was labeled an anti-vaxxer, because she believes she is “pro-science.” But, she explained, she is also “confused by the ‘science’ on both sides” of the vaccine debate and is skeptical of “Big Pharma.”

Her positions on health and science aside, Williamson’s supporters believe she can heal the country in the way they think she has healed them. Meghan Russell, a 39-year-old production assistant from Ohio, said she thinks Williamson could even win over Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY). “It’s going to be really hard to be combative with her, because it’s really hard to fight with somebody who’s not interested in your version of reality,” she said.

Barbara Tavres, a 59-year-old community relations manager at a book store Williamson has been making regular appearances at for years, echoed the sentiment. “She probably has higher intelligence than anyone else on the planet, because she’s got body, mind, and soul, all three cylinders, fired up at the same time,” she said.

Tavres also stressed the importance of Williamson’s HIV/AIDS advocacy and attention to the LGBTQ community, dating back to the 1980s. Amid the HIV/AIDS crisis, Williamson held support groups for HIV-positive patients, and in 1989, she founded Project Angel Food, which delivered meals to the homes of HIV/AIDS patients and others with life-threatening illnesses. Today, the project has served over 11 million meals.

It’s not just the longtime Williamson fans that seemed pretty willing to put trust in her. Sarah Barrick, a 27-year-old social media consultant from Brooklyn, literally did not know Williamson existed before the Democratic debates. After seeing her — or rather, after seeing the memes about her on debate night — Barrick volunteered for the campaign and along with others launched a Williamson-dedicated meme page. “It kind of doesn’t matter what the particulars are, because she could be corrected when people disagreed with a stance. She wouldn’t hold her stances hardcore,” she said.

“Marianne or bust” probably isn’t a thing

The memeification of Williamson before and after the debate has created this situation where some support for her is ironic, some is genuine, and some is both. Does the whole spirituality, self-help thing sometimes come off as a little weird? Sure. But plenty of people are also into it.

There was some defensiveness among Williamson’s longtime followers, who seemed bothered by some of the jabs. Two mentioned Kate McKinnon’s impersonation of Williamson on Late Night with Seth Meyers specifically. Most of them generally shrugged it all off and acknowledged that some of what Williamson says, at least from the outside, can seem a little odd. But there was also a very genuine sense that it was unfair and even hurtful. Hillary Clinton in 2016 had a slogan of “Love trumps hate,” and she wasn’t widely mocked for it.

“If she was a reverend within the Christian faith, you guys wouldn’t be out there criticizing her for her faith. You’re only weaponizing her faith and spirituality because it doesn’t align with your own,” said Stephen Savage, 38, the head of sales for a mobile retail technology company in Nashville.

“Everybody’s so snarky and mean because they don’t know what to do with life, they don’t know what to do with somebody who’s full of positive consciousness,” said Michelle Casto, a 50-year-old career coach and teacher from Kentucky. In an email before agreeing to speak with me, Casto sought my assurance that I was working on a “serious article that addresses issues and not a MOCKING one.”

“She’s not what reporters and political pundits are saying, a crystal hippie woo-woo,” Tavres said.

(I asked several of Williamson’s followers if there were crystals involved in her lectures or teachings, since that’s become such a running joke. They all laughed and said no. In other words, they’ve been dealing with others poking fun at them for a while.)

Williamson will likely qualify for the debate stage in July, but she’s still barely registering in the polls. She is as long-shot of a candidate as they come. In other words, she is probably not going to be the Democratic nominee.

None of the backers I spoke to were “Marianne or bust.” They said they were interested in plenty of other candidates — Andrew Yang, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Tulsi Gabbard — and would happily vote for the others, at least eventually. But they’re going to stick by Williamson as long as she’s in the race.

Charles Raffaele, a 31-year-old PhD student from Queens, told me in 2016 he supported Sanders but after discovering Williamson earlier this year on social media and seeing her debate performance, he’s volunteering for her campaign. He figures he can help her more than he can Sanders for the time being. “He doesn’t need my support right now in order for him to be one of the main candidates,” he said.

Savage said he thinks Williamson would bring about a future with a “renaissance of consciousness,” but he’s happy to pivot to other 2020 Democrats at some point. “The fact of the matter is, of any of those people who were on that debate stage, whoever’s on that ticket, I’m voting for them,” he said. “But I think that when it comes to who’s got the most inspiring and interesting things to say, Marianne is my girl.”

Sourse: vox.com