A new EPA rule imposes federal regulations for the first time. Here’s what you can do on your own.

According to a study by the US Geological Survey, nearly half of the tap water in the United States is contaminated with “forever chemicals” that are considered dangerous to human health. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images Li Zhou is a politics reporter at Vox, where she covers Congress and elections. Previously, she was a tech policy reporter at Politico and an editorial fellow at the Atlantic.

The Environmental Protection Agency has set the country’s first federal limits on forms of PFAS in drinking water, a class of “forever chemicals” that have been tied to negative health outcomes and have been found in one form or another in nearly half of the US’s tap water supply.

The policy could help improve the water quality of as many as 100 million people.

Having a standardized federal policy will eventually take the pressure of monitoring drinking water off of individuals, who currently have to do so in most states. The proposal, however, falls short of calling for companies that have utilized PFAS heavily — like DuPont and 3M — to curb their usage or cover cleanup costs, a move that experts say is needed to fully address the problem of these contaminants.

“The issue and the cost and the burden of all this shouldn’t fall on communities, it shouldn’t fall on the consumer. It’s the polluter that needs to pay,” Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist at the Environmental Working Group, told Vox last year.

Instead, the EPA’s new rule — which is the first new standard for a contaminant in drinking water in almost three decades — will require utilities to test for and reduce the levels of some forms of PFAS to four parts per trillion. All told, the policy covers six forms of these forever chemicals, and can be enforced by the EPA if the necessary thresholds aren’t met. It will take full effect in 2029, giving utilities both time to test water quality and to make equipment changes needed to improve it.

In the meantime, there are things individuals can do to reduce their exposure to the chemicals: First, they can check with their public utility about whether there has been PFAS detected in their area. (If they use a private well, they can get it tested.) And if PFAS has been found in their water supply, they can utilize filtration systems to screen it out.

“The first step is the education piece of it, finding out if there is PFAS in your water,” Stoiber said. “A lot of these filters are quite effective at removing PFAS. And that’s a step that people can take.”

What are PFAS, why are they bad, and are they in my water?

PFAS, which is short for per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances, are chemicals that repel oil and water, and that take a very long time to break down (which is why they’re commonly referred to as forever chemicals).

Exposure to PFAS, which is found in everything from nonstick pans to firefighting foam to outdoor gear, has also been linked with certain medical conditions, including cancers, hypertension during pregnancy, and weakened immune systems in children.

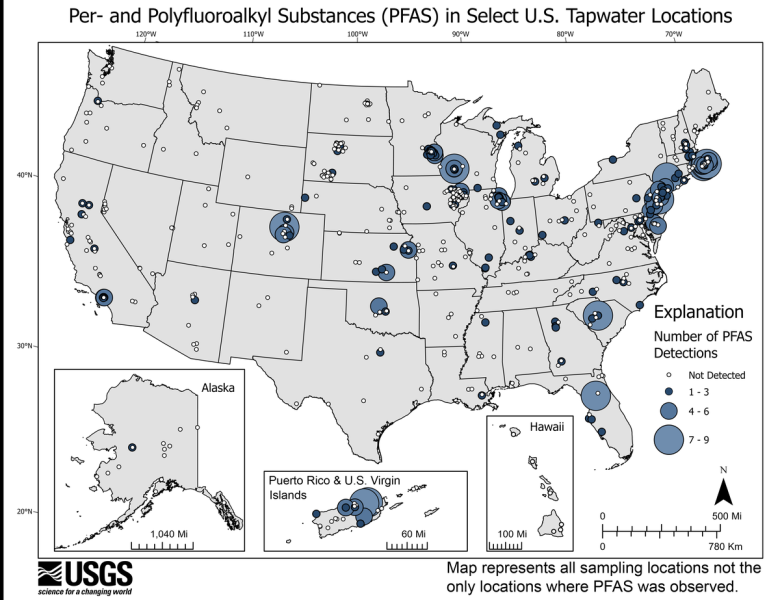

A 2023 report from the US Geological Service examined tap water over the course of five years at 716 locations including people’s homes and offices. It screened for 32 individual PFAS compounds, and found the highest concentrations of these chemicals in urban areas and specific regions including the Great Plains, Great Lakes, Eastern Seaboard, and Central and Southern California.

These higher concentrations are likely tied to the prevalence of PFAS around production facilities and other sources such as landfills and wastewater plants. Places with more people could also have a higher presence of PFAS because more products containing these chemicals are in regular use.

PFAS has been detected in higher concentrations in certain parts of the country. USGS

The release of the study follows the Environmental Protection Agency’s advisories in June 2022, which warned that the presence of PFOA and PFOS, two of the most common forms of PFAS, could be hazardous, including at low levels.

Now, the EPA’s rule specifically requires the presence of PFOA and PFOS in water to be no more than four parts per trillion. It also requires that the presence of three other chemicals — PFNA, PFHxS and GenX — to be no more than 10 parts per trillion. (Environmental experts have urged the EPA to include more PFAS, a class of chemicals that includes thousands of compounds, in the rule.)

The agency estimates that 6 to 10 percent of public utilities will have to make changes to their water filtration system in response to the regulation.

How to filter PFAS out of your tap water

It will be five years before utilities will have to completely comply with the PFAS levels set by the EPA.

Prior to those regulations going into place, however, individuals can still take steps on their own.

As the 2023 USGS report noted, different types of PFAS exist in different concentrations in drinking water across the country. The first thing that anyone concerned about PFAS should do is to figure out whether it’s present in the region they live in and at what levels.

“If the person has publicly supplied water, they should be able to obtain a report from their local utility. Otherwise, they also can search the tap water database from the Environmental Working Group,” Jamie DeWitt, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at Eastern Carolina University, told Vox last year when the USGS study was released. “If the person is on a private well, unless they are covered by a court order due to known contamination, they will have to send their water out for testing on their own. Many departments of public health have recommendations on where water can be sent for different types of testing.”

Stoiber notes that any level of PFAS is concerning and recommends the filtration of drinking water across the board. “Really, you don’t want any level of PFAS in your water because it has been linked to harmful health effects at quite low levels,” she told Vox.

There are a range of water filters that can target PFAS, but they vary in efficacy. According to a 2020 study and the experts Vox spoke with, a reverse osmosis water filter is the most effective tool for removing PFAS.

That review found that these water filters — which can be installed under a kitchen sink — are over 90 percent effective at screening out these chemicals. The filters work by sifting water through a membrane that has very “tiny holes,” says Stoiber, and the PFAS molecules get trapped as a result. The downsides of reverse osmosis filtration systems are that they waste significant amounts of water and can be pricey, costing anywhere from hundreds to thousands of dollars.

Activated carbon filters can also reduce levels of PFAS, but were found to be less effective, according to the 2020 study. These types of filters were able to remove, on average, 73 percent of PFAS contaminants, though there was more variability. They work by attracting PFAS molecules to carbon and can be used in sinks, refrigerators, and pitchers. And while they are more cost-effective, they also have to be replaced promptly, or else their efficacy declines. Standard Brita water filters use a form of carbon technology and can remove some PFAS, but aren’t built for this express purpose, so shouldn’t be counted on solely to filter out the chemicals.

When it comes to PFAS, experts note that filtered water is a better option than switching exclusively to bottled water, which can be costly, wasteful, and potentially include its own contaminants. They say, too, that ingestion poses the biggest risk of PFAS exposure relative to other water uses like showering, hand-washing, and clothes washing. If you can, the best thing to do is to filter your own water if you live in a contaminated area.

“Bottled water is known to have high concentrations of PFAS. There was a case in Massachusetts a couple of years ago where bottled water had very high concentrations of PFAS in it because it was sourced from PFAS-contaminated water,” Harvard environmental chemist Elsie Sunderland previously told Vox’s Benji Jones. “So I think you’re better off drinking filtered water from a known source.”

Update, April 11, 10:14 am ET: This story, originally published July 7, 2023, has been updated once with news of the EPA’s new regulation.

Sourse: vox.com