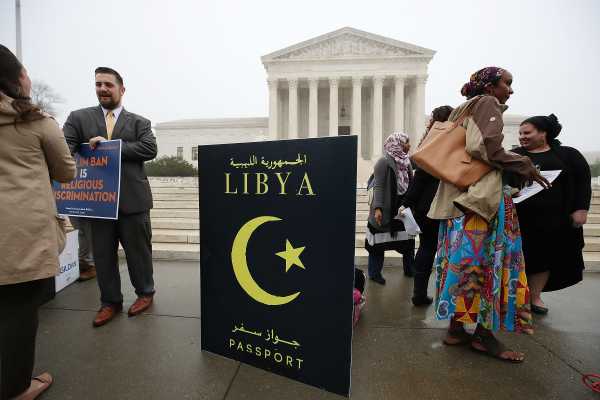

Wednesday morning’s Supreme Court oral arguments in Trump v. Hawaii — the case over President Donald Trump’s third version of the “travel ban” on immigrants and temporary visitors from several countries, most of which are majority Muslim — didn’t make the Court’s job in deciding the legality and constitutionality of the ban any easier.

Solicitor General Noel Francisco, arguing (for the government) that the ban should be allowed to continue, gave a strong performance that stuck to his side’s strongest arguments. So did Neal Katyal, arguing (for the state of Hawaii and other organizations suing the administration) that the Supreme Court should uphold a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling that would have stopped the ban from being enforced. (The Supreme Court ruled in December that the ban should remain in effect until it weighed in more fully this spring.)

If any of the nine justices were on the fence and looking to Wednesday to give them a clear answer, they were probably out of luck.

In Trump v. Hawaii, the Court is looking to answer four questions when it issues its ruling near the end of June. It’s trying to answer whether the ban is legal via a provision of immigration law that allows the president to “suspend” the entry of “any class of aliens,” and whether it’s constitutional in light of the First Amendment’s ban on a government establishment of religion. (There are also two procedural questions that the justices didn’t spend much time on, about whether the Court can hear this case at all and about whether the ban should have been stopped nationwide by lower courts.) The Court will have to answer yes to both main questions to let the ban stand.

Of course, it’s impossible to tell when the justices have made up their minds — at least until they release their opinion in a case. (Because this case was heard on the last day for oral argument before the Supreme Court takes its summer recess, and because it’s such a big deal, it probably will not be released until the last week of June.)

Reading tea leaves from oral argument is usually foolish. But the Supreme Court has been more favorable to the administration than lower courts have been in the past. And the two likely swing votes in the case — Justice Anthony Kennedy and Chief Justice John Roberts — seemed more worried about the precedent they would set by voting against the ban than the precedent they’d set by voting for it.

The pro-ban argument: the president has latitude on national security and foreign policy, and the ban involves both

The federal government’s argument, as presented by Francisco, was a new variation on a theme the Trump administration has pushed for the entire 15-month court battle over the travel ban: that this is a matter of national security, and on national security, the executive branch has a lot of power over both Congress and the courts.

The government argues the ban is covered by a provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act that allows the president to suspend entry of “any aliens, or any class of aliens,” if he finds they could be a threat to the US.

Francisco argued that the government was only targeting countries that didn’t give the United States enough information for US officials to judge whether someone ought to be admitted to the country under existing law — so the ban was needed to enforce the rest of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

More importantly, he argued, the point of the ban was to exert “diplomatic pressure” on targeted countries, to force their governments to start providing that information.

The courts give the executive branch a ton of leeway when it comes to foreign policy, so this argument seemed designed to lead the court to find that the ban was within the president’s power.

The anti-ban argument: the president is trying to solve a problem Congress already solved

Katyal, arguing against the ban, also focused on the legality of the ban rather than its constitutionality. But he argued that the justification for the ban — insufficient information sharing and state tolerance of terrorism — was already a problem Congress knew about, and that it passed laws to address the problem that weren’t as blunt as country-based bans.

Because the president isn’t supposed to usurp Congress’s functions, Katyal argued, the executive can’t present an additional solution to a problem Congress already solved and pretend it’s a new problem.

Kennedy and Roberts did not appear particularly persuaded by this argument. They raised concerns that ruling against the ban would make it impossible for the president to stop terrorists from entering the US in other cases — presenting “ticking time bomb” scenarios in which a ban might be justified, or changes to foreign policy that might lead the president to act unilaterally.

The anti-ban argument: the president could have disavowed his Islamophobia, but instead he embraced it

When it came to the constitutionality of the travel ban — in particular, whether it violates the First Amendment’s prohibition on a state establishment of religion — both sides agreed (or conceded) that the original “Muslim ban” proposed in December 2015 would have been unconstitutional, and that if the current ban from September 2017 had been Trump’s only activity on the matter, it would be constitutional. The question is how to judge the current ban given the existence of the past bans (real and proposed).

For Katyal and the liberal justices, the obviousness of Trump’s initial “animus” against Muslims makes it irresponsible to pretend that the current ban exists in a vacuum. Justice Kagan asked a powerful hypothetical about an anti-Semitic president who ordered his Cabinet secretaries to find a way to ban Jews and ultimately banned Israelis; when Francisco protested that Israel was an ally, she quipped, “This is an … out-of-the-box president, in my hypothetical.”

Katyal agreed that there were cases in which a president could wash his hands of the statements he made before the election. He argued that Trump and his advisers didn’t do that — explicitly mentioning one tweet in which Trump promised to come back with a stronger version of the ban that wasn’t “politically correct.”

The pro-ban argument: after the inauguration, the ban wasn’t about Muslims

For Francisco, arguing for the government, there was a bright line at inauguration. Before taking the oath of office, Trump was a private citizen; afterward, he was bound by the Constitution. And since none of the actual bans signed were explicitly religious — and the current ban was preceded by an interagency review process — that washes it of any Islamophobic “taint.”

The government relied on the idea that because the Cabinet had conducted the review process that led to the current ban, it wasn’t just about the president — it was about the entire executive branch.

Perhaps most importantly, at the end of his rebuttal, Francisco argued that President Trump did deny the latest ban was a “Muslim ban” when he signed it in September, a challenge the critics didn’t get the chance to answer.

The Court might be more concerned with the implications of a ruling for the future than it is with the present — and the president

It’s notoriously easy to misjudge how the Supreme Court will rule based on oral arguments. That said, the liberal justices — Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan — were clearly more skeptical of the government than they were of the ban’s critics.

Conservative Justice Samuel Alito was clearly more supportive of the government. Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch appeared to side with the government as well. (Clarence Thomas didn’t speak, as usual, but he can safely be assumed to side with the conservatives.)

Kennedy and Roberts asked questions of both sides. They didn’t tip their hand as readily as the liberal justices or Alito did. But they appeared most worried about the national security implications of striking down the ban — with the idea that this would limit some future president from doing what needed to be done to keep America safe.

In other words, they were not primarily concerned with what this president, Donald Trump, might be doing now or might do in future.

Trump has often inspired the question of whether it’s a good idea for a president to have this much power, if this president might use it this way. If a majority of the Supreme Court shares that worry, they didn’t show it Wednesday.

Sourse: vox.com