From ballot initiatives to local elections to the state and federal races, the 2018 midterm elections will give voters an opportunity to define the system charged with arresting, prosecuting, and incarcerating people in America.

These races usually do not get the attention they deserve, especially state and local elections and particularly races for prosecutors. But they are tremendously important: Despite all the attention that goes to the federal system, the great majority of criminal justice work is done at the local and state level, where America’s police departments operate and most of the people in prison are locked up.

A criminal justice reform movement, galvanized by Black Lives Matter, civil rights issues, and prison spending’s strain on government budgets, has already led to some changes in recent years, from reforming prisons and police to reducing criminal penalties for certain crimes. The 2018 midterms offer an opportunity to continue the momentum behind criminal justice reform.

Here are some of the most pressing criminal justice issues on the ballot this November, covering debates over the war on drugs, mass incarceration, policing, crime victims’ rights, and more.

Criminal justice issues on the ballot in six states

First, several states — notably Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, Ohio, Oregon, and Washington — will have a diverse set of big ballot initiatives related to the criminal justice system. Here’s a rundown of the major proposals:

- Colorado’s Amendment A: Under the Colorado Constitution, slavery and involuntary servitude are allowed “as a punishment for crime.” (The US Constitution has a similar exemption in the 13th Amendment’s ban on slavery.) Amendment A would remove the exception in the Colorado Constitution, effectively prohibiting the state government from forcing people convicted of a crime into labor or work.

- Florida’s Amendment 4: Florida is one of three states where people convicted of felonies can’t vote even after they’ve completed their sentences (including prison, parole, and probation). Amendment 4 would automatically restore people’s voting rights after they finish their sentences. It needs 60 percent of the vote to pass under Florida’s standards for constitutional amendments.

- Florida’s Amendment 11: Under the Florida Constitution, the repeal or reform of criminal laws can’t be applied retroactively, so someone sitting in prison for, say, marijuana possession would be kept in prison even if pot was legalized. Among other changes, Amendment 11 would repeal the prohibition on retroactivity, allowing changes to criminal laws to apply retroactively. It needs 60 percent of the vote to pass under Florida’s standards for constitutional amendments.

- Louisiana’s Amendment 1: A 2016 court ruling allowed people convicted of felonies to seek public office in Louisiana immediately after they complete their sentences. Amendment 1 would ban them from doing so until five years after they complete their sentences, unless they are pardoned.

- Louisiana’s Amendment 2: Louisiana is one of two states, along with Oregon, that allows non-unanimous jury verdicts in felony trials. The law was an effort to constrain the power of black jurors, coming out of a constitutional convention in 1898 meant to “perpetuate the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon race in Louisiana.” Amendment 2 would require juries to reach unanimous decisions in felony trials, aligning Louisiana with all other states except Oregon.

- Ohio’s Issue 1: Under Ohio law, drug possession can be a felony, resulting in jail and prison time. Issue 1 would change that, reducing all drug possession offenses to misdemeanors. It would also make it harder to imprison or jail people for such offenses, aim to reduce the use of prison time for non-criminal probation violations, and allow people in prison, except those incarcerated for murder, rape, or child molestation, to seek sentence reductions up to 25 percent if they participate in rehabilitative programs, up from 8 percent under current rules. It would apply the financial savings (from having fewer people in prison) to addiction treatment programs and crime victim funds.

- Oregon’s Measure 105: Oregon currently restricts the use of state resources or personnel to help the federal government with immigration law enforcement, making it a “sanctuary state.” Measure 105 would repeal the ban, allowing Oregon officials and police departments to cooperate with the feds to crack down on illegal immigration.

- Washington’s Initiative 940: Like police agencies in other states, Washington police departments have come under fire for excessive use of force, particularly against racial minorities. Initiative 940 would change the standards allowing use of force, imposing a “good faith test” that, in short, would create extra checks to ensure use of force was truly justified. It would also mandate independent investigations into police officers’ use of force that results in serious injury or death. And it would require all police officers in the state to get deescalation and mental health training, and create a duty for them to provide first aid.

With the exception of Louisiana’s Amendment 1 and Oregon’s Measure 105, the overall goal of these measures is to make the criminal justice system less punitive — to cut back on incarceration, to reduce punishment, and to reel in police practices that many see as too brutal.

In this way, the ballot initiatives speak to the broader criminal justice reform movement that’s occurred in the past few years. Facing the highest incarceration rates in the world, and the costs that locking up so many people entail (from financial to social), America has tried to reel back policies that perpetuated mass incarceration and the war on drugs. Most of these initiatives would continue that trend.

Marijuana legalization in Michigan and North Dakota, and medical pot in Utah and Missouri

Marijuana legalization has already had a very big year, with Vermont and Canada legalizing cannabis for recreational use, Oklahoma legalizing it for medical purposes, and California opening its recreational marijuana market. But in the midterm elections, there will be a few more opportunities for voters to legalize pot for recreational or medical uses. Here are all the state proposals:

- Michigan’s Proposal 1: This would legalize the possession, use, purchase, sales, and home growing of marijuana for recreational purposes for adults 21 and older, and set up a system for regulating and taxing cannabis sales.

- North Dakota’s Measure 3: This would legalize the possession, use, purchase, sales, and growing of marijuana for recreational purposes for adults 21 and older. But unlike most successful marijuana legalization initiatives, it does not set up a regulatory framework for how cannabis producers and shops in the state would operate. Instead, Cole Haymond, an adviser for the Measure 3 campaign, told Christopher Ingraham at the Washington Post, “We leave our bill wide open so the legislature can do their job — regulations, taxes, zoning, whatever.”

- Utah’s Proposition 2: This would legalize medical marijuana, letting patients get medical marijuana cards via doctors’ offices and creating a regulatory system for dispensaries. The proposal has been very controversial in conservative Utah, but lawmakers said they will pass a compromise bill that would enact a more restrictive version of medical marijuana — and override the ballot measure, should it win.

- Missouri’s Amendment 2, Amendment 3, and Proposition C: These three measures all legalize medical marijuana, but they do so in different ways. (For a full breakdown of the differences, read my explainer.) If all three pass, state law dictates that the constitutional amendments and the measure with the most votes take priority.

At this point, marijuana legalization can seem less eventful, given that nine states have legalized for both recreational and medical purposes and 21 others have for just medicinal uses. But these measures are still a big deal; they involve radically rethinking the war on drugs that has driven so much of US criminal justice policy over the past few decades. With every win that marijuana legalization gets at the ballot box, voters are saying no more to the punitive regime that’s been with us for a very long time.

Marsy’s Law, a crime victims’ bill of rights, is on the ballot in six states

Several states are voting on what’s known as “Marsy’s Law”: Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Nevada, North Carolina, and Oklahoma.

Marsy’s Law is a crime victims’ bill of rights, aiming to ensure that victims — often defined to include not just the direct crime victim but also their family members — are heard and protected throughout the criminal trial process. Named after the murdered sister of Marsy’s Law for All founder Henry Nicholas, the law gives the victims, as defined under the initiative, the right to, for example, be told about criminal proceedings, be present at proceedings, be heard at proceedings, and be protected from the accused.

The Marsy’s Law campaign explained why such protections are, in its view, necessary:

The movement for Marsy’s Law has taken off since 2008. California, Illinois, Montana, North Dakota, Ohio, and South Dakota each approved a version of it, although it was struck down in Montana by the state’s Supreme Court.

But the laws have become very controversial among some criminal justice reformers. The American Civil Liberties Union summarized its general opposition to Marsy’s Law in a blog post by ACLU of New Hampshire policy director Jeanne Hruska earlier this year, arguing that the law undermines due process protections and may end up unworkable.

One concern is that the law creates a false dichotomy between victims’ and defendants’ rights, as if the victims and defendants are the two sides facing off in a trial. But a trial is really the government versus the defendant. This distinction is crucial for understanding why the criminal justice system works as it does.

“Defendants’ rights only apply when the state is attempting to deprive the accused — not the victim — of life, liberty, or property,” Hruska wrote. “They serve as essential checks against government abuse, preventing the government from arresting and imprisoning anyone, for any reason, at any time.”

Yet in creating this dichotomy, Marsy’s Law may, Hruska went on, empower the state, through the victim, against criminal defendants — potentially giving the criminal justice system even more power to prosecute and incarcerate people, including those who may not even be guilty of the crimes that they’re accused of.

“Creating such a conflict [between victims’ rights and defendants’ rights] means that defendants’ rights may lose in certain circumstances,” Hruska claimed. “This result accepts that defendants’ rights against the state will be weakened or unenforced in some cases, potentially at a significant cost to constitutional due process.”

There are ways, she wrote, to protect crime victims’ rights without such downsides. In New Hampshire, as one example, victims’ rights are protected “to the extent … they are not inconsistent with the constitutional or statutory rights of the accused.” Marsy’s Law doesn’t typically include such limitations.

Another question is how, exactly, Marsy’s Law will be implemented. “For instance, Marsy’s Law includes a constitutional right to privacy for victims, yet it is impossible to know what that right would encompass in practice,” Hruska argued. “Would it prevent the release of names or crime reports? Would it reduce the amount of information that press outlets are allowed to provide to the public regarding crimes? Could it give a victim and their attorney control over the limits of a victim’s testimony at trial?”

Beth Schwartzapfel at the Marshall Project reported on major implementation problems in South Dakota:

It’s not that the ACLU and other criminal justice reformers oppose legally protecting victims’ rights. Many states, in fact, have crime victim protections that reformers don’t object to. It’s that, in their view, Marsy’s Law is not the right way to protect these victims.

This speaks to a recurring problem in the criminal justice system: There is often a desire to find quick, simple solutions — say, more incarceration or stricter penalties for drug offenses — to the big problems that the system is in charge of overseeing. There’s a big crime wave, but, policymakers thought, if we lock up all these people for as long as possible, they won’t be able to commit all this crime. Drug use and addiction are ravaging communities, but, the thinking went, people will stop using drugs if there’s a threat of serious punishment.

The desire for such solutions is understandable, given some of the grave social problems involved. But often, the proposed solutions lead to unintended consequences — and, as the research shows with mass incarceration and punitive sentences for drugs, may not even be an effective way to stop the problem that the solution intends to address. That’s what critics fear may end up happening with Marsy’s Law.

Prosecutor elections: maybe the most important contests in criminal justice

In some states, voters will elect arguably the most powerful person in the criminal justice system: the prosecutor.

Prosecutors are enormously powerful in the US criminal justice system, in large part because they are given so much discretion to prosecute how they see fit. For example, former Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson in 2014 announced that he would no longer enforce low-level marijuana arrests. Think about how this works: Pot is still illegal in New York state, but Brooklyn’s district attorney flat-out said that he would ignore an aspect of the law — and it’s completely within his discretion to do so.

Prosecutors make these types of decisions all the time: Should they bring the type of charge that will trigger a lengthy mandatory minimum sentence? Should they bring a charge that’s only a misdemeanor? Should they strike a deal for a lower sentence, but one that can be imposed without a costly trial?

We see this in police shooting cases. Prosecutors have the power to decide whether to bring charges against police officers, and are also given enormous power over grand juries to get an indictment (hence the saying that prosecutors can get grand juries to “indict a ham sandwich”) and in the courtroom generally.

Courts and juries do, in theory, act as checks on prosecutors. But in practice, they very often don’t: More than 90 percent of criminal convictions are resolved through a plea agreement, so by and large, prosecutors and defendants — not judges and juries — have the biggest say in the great majority of cases that result in incarceration or some other punishment.

Prosecutors have also played a major role in perpetuating mass incarceration. Analyzing data from state judiciaries, John Pfaff, a criminal justice expert at Fordham University, compared the number of crimes, arrests, and prosecutions from 1994 to 2008. He found that reported violent and property crime fell, and arrests for almost all crimes also fell. But one thing went up: the number of felony cases filed in court.

Prosecutors were filing more charges even as crime and arrests dropped, throwing more people into the prison system. Prosecutors were driving mass incarceration.

Pfaff provided a real-world example of this kind of dynamic in his book Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform: “Take South Dakota, which in 2013 passed a reform bill that aimed to reduce prison populations. The law did lead to prison declines in 2014 and 2015, yet at the same time prosecutors responded by charging more people with generally low-level felonies, and over these two years total felony convictions rose by 25 percent.” In the long term, this could lead to even larger prison populations.

Now apply this story on a national scale. There is less crime compared to the 1990s. Police are making fewer arrests. Lawmakers are slowly reducing the length of prison sentences. Yet until 2010, incarceration rates had continued to climb nationwide — and, as Pfaff pointed out, the recent drop in incarceration would be much less pronounced if it weren’t for court-ordered drops in California’s prison population. Prosecutors have been abetting more and more incarceration while other actors in the system have been pulling back.

By electing progressive prosecutors, voters could start to change this dynamic. This has started to happen in some parts of the country, including St. Louis County, Philadelphia, and Cook County, Illinois, where Chicago is. But to achieve this across the country, voters will need to pay attention to races that they have historically neglected.

To see if a local prosecutor race is going on in your area this November, I recommend local news outlets, the League of Women Voters’ guide to this year’s elections, or Color of Change’s prosecutor directory. If you care even slightly about criminal justice issues, you should get familiar with these officials — because they are very powerful under the current system.

Other local and state races will be a big deal too

Beyond prosecutors’ elections, there will be many local and state elections that will shape the criminal justice system for years to come. Some of these races will be for officials directly involved in the criminal justice system, such as sheriffs, judges, and attorneys general. Others will be for local and state lawmakers, who, well, make the laws that the criminal justice system then enforces.

Although most of these races are bound to get much less attention than congressional elections, they are far more important than the US House of Representatives or Senate when it comes to the criminal justice system.

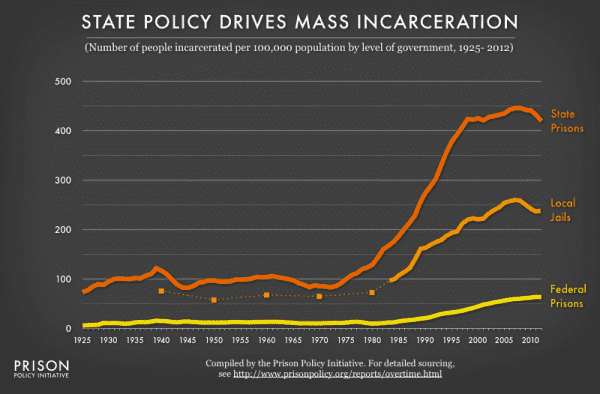

Consider the statistics: According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 87 percent of US prison inmates are held in state facilities (and most state inmates are in for violent crimes, not drug crimes). That doesn’t even account for local jails, where hundreds of thousands of people are held on a typical day in America. Just look at this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative, which shows both local jails and state prisons far outpacing the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons:

One way to think about this is what would happen if President Donald Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 593 per 100,000 people, only the small nation of El Salvador would come out ahead — and America would still dwarf the incarceration rates of other developed nations like Canada (114 per 100,000), Germany (78 per 100,000), and Japan (45 per 100,000).

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 police agencies in America, only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall almost wholly to local and state governments. So to influence major changes, voters will, once again, have to pay attention to races they haven’t paid much attention to in the past.

For details about local candidates, I again recommend local news outlets or the League of Women Voters’ guide to this year’s elections. For state candidates, I recommend the ACLU’s guide to the 2018 elections.

However you vote, you can bet the outcome will have an impact on mass incarceration, the war on drugs, and the criminal justice system more broadly.

Sourse: vox.com