Continuing her streak as the 2020 presidential cycle’s most policy-rich candidate, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) rolled out a package of proposals on Wednesday designed to boost the fortunes of America’s small farmers, instead of the agribusiness giants who increasingly control the sector.

With Iowa playing a perennially influential role in the US presidential nominating process, Midwestern farmers always get some love from candidates. But Donald Trump’s unusually strong electoral performance in the rural north and the collapse of the once-large bloc of Democratic Party senators from the Great Plains states has transformed the political geography of the United States to the GOP’s advantage.

This transformation has been driven by identity issues: Democrats are increasingly branded not just as the party of racial minorities, but more broadly as the party of people who enjoy the cosmopolitan lifestyles available in big metro areas and college towns, with the GOP representing the home-and-hearth values of smaller communities.

Warren’s pitch aims to inject a rural-specific economic clash into the political discourse that would fit neatly with her larger theme of attacking concentrated economic power and pit at least some farmers’ bottom-line economic interests against those of big corporate players in the farm sector.

Here’s how it works.

An anti-trust agenda for American farmers

The biggest element of Warren’s plan is a series of proposals related to anti-trust policy. She offers a variety of critiques of the status quo, but the best way to understand her point is probably to start from a very high level.

The “consumer welfare” standard has prevailed in US anti-trust policy for the past few generations. So if a small number of agribusiness middlemen with efficient operations can gobble up a huge share of the market for some commodity and squeeze farmers to offer lower prices, that’s fine — as long as even a tiny bit of the savings are passed forward to end users. In fact, even just one company more or less completely monopolizing the market for a given commodity would be fine as long as the monopolist uses its monopoly power to hurt producers rather than consumers.

Democrats have been challenging this concept in recent years in a variety of ways. (It was part of congressional Democrats’ official “better deal” agenda rolled out in 2017, Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) has been pressing the FTC to revise its practices, and Warren herself has been challenging Silicon Valley on this score for years.) But Warren is delivering a particular focus on the implications of the consumer welfare standard for the farm economy.

The original political mobilization against monopolies in the Populist and Progressive eras very much envisioned protecting farmers’ interests over that of middlemen (railroads, etc.) as part of its vision of the American economy, but the American legal and regulatory system has almost entirely abandoned this idea since 1980.

In a Medium post on her proposals, Warren promises to “appoint trustbusters to review — and reverse — anti-competitive mergers, including the recent Bayer-Monsanto merger that should never have been approved.” She also says that her “team will be committed to breaking up big agribusinesses that have become vertically integrated and that control more and more of the market,” while also arguing that consolidation outside of the agriculture sector (especially in transportation and health care) has also hurt rural America.

As you might expect from a politician, she does not bite the bullet and explicitly say that she would break up agribusiness conglomerates, even when doing so would lead to higher food prices for consumers. But that’s the logic of both her specific proposal on rural America and also her broader thinking on corporate power — that in the long run, a more democratic economy will serve society’s interests better than a narrow focus on consumer prices.

But wait, there’s more!

The anti-trust agenda is the centerpiece of Warren’s proposal, but it’s far from the end of it.

As Tim Lee reported back in 2015, one unintended consequence of the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act is that since modern cars now incorporate software, carmakers can invoke anti-piracy laws to make it illegal for car owners to repair their own cars. This hasn’t proven to be a big issue in practice in the auto market (at least not yet), but it is something many farm equipment manufacturers are taking advantage of to force farmers into exclusive maintenance relationships with authorized dealers. Warren proposes to ban that practice.

She also wants to restrict the ability of commodity checkoff programs (organizations like the Egg Board, the National Pork Producers Council, the National Dairy Council, etc.) to engage in anti-competitive practices. And she’s promising to copy Trump’s aggressive use of discretionary presidential authority over trade to force Canada and Mexico to go back to accepting country-of-origin labeling that would distinguish American livestock from foreign livestock.

Last, but by no means least, she proclaims her support for an Iowa law that sought to prevent foreigners from buying American farmland and says she will “use all available tools to restrict foreign ownership of American agriculture companies and farmland,” as well as deploying the federal government’s ability to crack down on various loopholes foreigners can exploit to get around the law.

Does this actually make sense?

Rural Americans believe profoundly and sincerely that they and their problems are overlooked and neglected in a society whose media and cultural tastemakers are increasingly based in big cities and reflect big cities’ cosmopolitan attitudes.

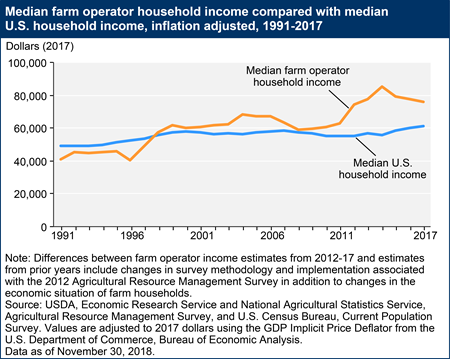

Especially in an environment where farm income has been falling steadily since 2012, Warren’s message could be welcomed as a sign by at least some rural whites that this is a Democrat who actually cares about them and has some ideas to help.

At the same time, objectively speaking, rural interests are massively overrepresented in the American political system, and despite several years of declining farm incomes, people who operate family farms have higher incomes than the typical American.

Under the circumstances, it’s easy as a city-dwelling cosmopolitan media elite to suggest that perhaps America’s farmers don’t actually have that much to complain about.

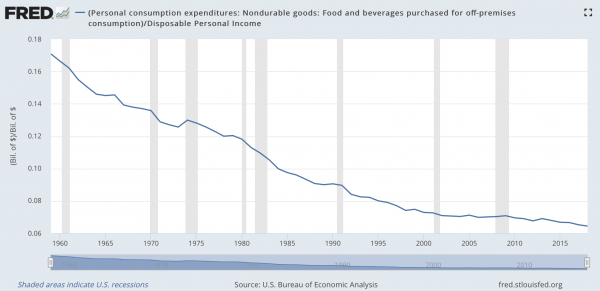

Then again, if one simply accepts that the overweighting of rural interests in American politics is a fixed element of the system, then the fact is that national politicians have an obligation to come up with ideas to serve rural communities. The dominant approach over the past generation has emphasized subsidies for bulk commodity production paired with a laissez-faire attitude to the supply chain, and that’s left actual farmers capturing a smaller share of overall food spending.

Food itself, meanwhile, has become incredibly cheap relative to Americans’ incomes, even as the cost of other key goods like health care, child care, and higher education has soared.

Warren’s economic agenda features the biggest and most aggressive proposals from 2020 candidates on housing costs and child care. Especially when viewed in that context, doing a little more on the food side to focus on farm incomes rather than agribusiness profits and cheap commodities is certainly a plausible answer to both the big picture of the American economy and the specific imperative to address rural voters.

Sourse: vox.com