Dean Phillips is trying to crash Joe Biden’s party. He picked a strange, strange place to start.

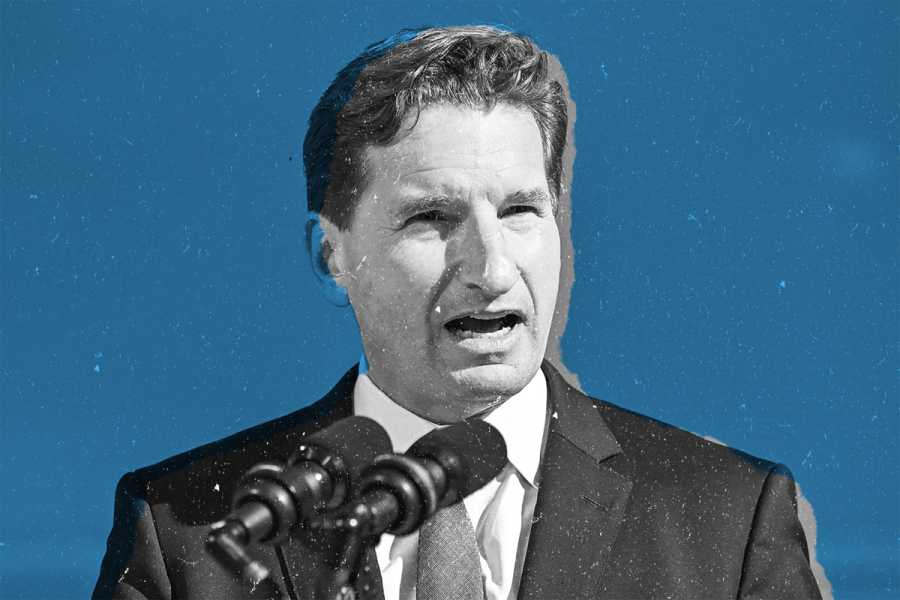

Democratic Rep. Dean Phillips of Minnesota. Vox; Gaelen Morse/Getty Images

Manchester, New Hampshire — “It makes me sick” to criticize President Joe Biden, Rep. Dean Phillips says in a windowless room of his campaign office, lined with “DEAN” posters as a perfect setting for filmed podcasts. “I’ve respected the president my whole life. I’ve had him in my home. … He helped save the country in 2020.”

Criticizing Biden, however, does not make Phillips too sick to refrain. “The way he’s acting now I think is real dangerous, isn’t it? He wouldn’t take my calls to even let him know that I was running. He’s not campaigning. He’s not consenting to debates. He’s not appearing in front of voters. He’s not answering questions. Where is he? And I’m concerned, because he’s going to get embarrassed by Donald Trump.”

That’s the basic thesis of the Minnesota congressman’s primary campaign for president: Voters think Joe Biden is too old and don’t want him to run again — and the polls prove it. “His numbers are horrible,” Phillips said. “He’s 81 years old. His time has passed, and he should have passed the torch.”

Polls of the 2024 presidential election have consistently shown Biden lagging behind Trump in a rematch. Further, a majority of voters have an unfavorable view of the incumbent, and polling data has shown that even Democrats are less than enthusiastic about a Biden reelection bid.

In fact, Phillips insisted that if the polls were better for Biden, he would have never thought of running. “Gosh no,” said the Minnesota Democrat. “But [they’re] not. And that’s why this is so existential in my mind. I’m dumbfounded that the great Democratic Party of which I have been a member and supporter and passionate about for so long is offering a singular candidate who is destined to lose to the most dangerous man in American history.”

As such, the 54-year-old Phillips is running a quixotic primary campaign against his party’s incumbent president.

But as he tilts at an octogenarian windmill, there are three major problems with Phillips’s run.

First, it’s starting in the strangest of settings: Biden will not even appear on the ballot in New Hampshire in a contest that the Democratic National Committee has stripped of delegates.

Second, in modern American history, the most successful primary campaigns against incumbent presidents have been based on policy differences. The efforts to primary Lyndon Johnson in 1968, Jimmy Carter in 1980, and George H.W. Bush in 1992 were all rooted in the fact that key segments of the primary electorate were disgruntled with the sitting president. In 1968, the issue was the Vietnam War; in 1980, it was inflation and the “malaise” looming over the Carter White House; and in 1992, it was about Bush’s support for increasing taxes during a recession. None of the three were successful, but they spoke to a real political divide.

Phillips’s campaign to primary Joe Biden is different. The three-term representative from suburban Minneapolis is not running as an ideological opponent of the incumbent president. In fact, his congressional voting record shows zero daylight between the two. Instead, he’s making the case that a 27-year age difference is what sets him apart, and why voters should consider him instead of the incumbent.

“If this time 13 months from now, a Democrat is in the White House, I will fulfill my most important mission,” he said. “And I simply believe that I am best positioned of the people in the race right now to be that person. I’m not saying I’m the only one. The whole point is, let’s determine that.”

He added that it could be “Joe Schmo. It could be Marianne Williamson, it could be Joe Biden, it could be me, it could be anyone. It could be names that we all know, it could be names that nobody knows. It could be Michelle Obama, for gosh sakes.”

But as he makes that case here, he’s running into a third problem: Running for president is hard.

The concept of a primary challenge to a vulnerable incumbent makes sense on paper, but the execution is difficult under the best of circumstances. It’s to be expected that the party’s loyalists will criticize you and left-leaning media will snub you. But Phillips is not running in the best of circumstances. Instead, he is mounting a last-minute effort that has sparked little enthusiasm from voters and has struggled to achieve the basic fundamentals of a presidential campaign.

New Hampshire’s messy Democratic primary, explained

What makes Phillips’s campaign in New Hampshire unique is that he is not even technically running against Joe Biden.

In 2022, Biden proposed a new presidential primary calendar — quickly rubber-stamped by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) — to end New Hampshire’s status as host of the first-in-the-nation primary. Biden bumped New Hampshire’s primary (and Iowa’s caucus, for that matter) from the front of the line. (By contrast, Republicans have kept the traditional primary calendar of the Iowa caucuses followed quickly by New Hampshire).

The Granite State, however, is famously protective of its primary, which it has enshrined in law. Further, with a Republican governor and Republican control of both chambers of the state legislature, there was no appetite to change that law. And so New Hampshire is holding its primary anyway on Tuesday, January 23, thumbing its nose at the national party.

There’s a price for defiance. The national party will award exactly zero delegates based on the vote, turning it into something of a beauty contest whose significance will be measured in, for lack of a better term, vibes.

And because of the primary’s rogue status, Biden’s campaign declined to put him on the ballot. Instead, there is an active write-in effort being mounted on his behalf, led by a number of Democratic stalwarts in the state. As Ray Buckley, the chair of the New Hampshire Democratic Party, told Vox, “The write-in effort has got the best of the best folks involved in it. So I could not ask for a better team, if I was hoping to get written in.”

As well as competing against the write-in effort, Phillips will share the ballot with nearly two dozen others, including failed 2020 presidential candidate Marianne Williamson and Vermin Supreme, a perennial candidate and performance artist best known for wearing a boot as a hat.

Why is either Biden or Phillips bothering at all, given that nobody will get delegates out of the contest? Because the write-in campaign is simply about shaping the media narrative. It means that Phillips is almost engaging in a form of glorified shadow boxing — particularly when an active Republican primary is drawing the attention of many unaffiliated voters who might otherwise cast a ballot in the Democratic race.

What does success look like in that boxing match? That’s not clear to anyone — including to Team Phillips.

The Phillips campaign has internally suggested that their benchmark is the 42 percent that fellow Minnesotan Eugene McCarthy received when he launched a primary challenge against Lyndon Johnson in 1968. But unlike McCarthy’s grassroots campaign, there is not a groundswell of activists looking to get “clean for Dean.”

Phillips seemed to be tempering expectations for his campaign and setting a high bar for Biden when he spoke to Vox. “Should [Biden] not get 90 percent of the vote, in the first-in-the-nation primary as incumbent president? I would imagine he should.” Barack Obama received only 81 percent of the vote of the state while running unopposed in 2012.

Who is Dean Phillips?

At a Nashua coffeehouse, Dean Phillips made his pitch. It was a tight space where two dozen voters were squeezed in along with reporters and Phillips’s own campaign entourage, including a camera crew.

He started with a capsule biography of himself as someone orphaned as an infant when his father died in Vietnam and then raised in a wealthy family after his mother remarried. Phillips then detailed starting a business and how he got into electoral politics when he woke up the morning after the 2016 election to his daughter crying about the result and decided he needed to do something.

He also described his disconnection once he arrived in Washington and how distastefully insular and partisan he found both the city and the reluctance of his fellow Democrats to call on Biden not to run again. As he characterized his conversations, “They’re all waiting until 2028. So I say, ‘You can’t wait until 2028. Because we may not have a 2028 if we allow [Trump] back to the White House.’” And then he pivoted to urge voters to back him: “The very state that was disenfranchised by the Democratic National Committee has the opportunity to shove it right back in their face, change democracy forever, and actually change the narrative of this entire campaign,” he said to applause.

Phillips took questions from the audience, which he handled with some practiced skill. When a questioner asked about what he described as his vaccine injury, Phillips deftly pivoted to talk about Medicare-for-all.

But much of what he offered was anti-politics that assailed business as usual in Washington, the lack of bipartisanship and imagination there, and the need for new blood. “As someone who has spent his career building businesses competing against two big brands — most recently Talenti Gelato against Ben and Jerry’s and Häagen Dazs — let me tell you, the Democratic and Republican parties need competition,” he said, decrying how the two parties kept members of Congress busy raising money rather than interacting with each other.

He went on to note of Biden, “When you’re 81 years old, I don’t know how you can have the capacity to start really getting your hands around something so significant as artificial intelligence, let alone Web 3.0 and crypto and blockchain.”

After the town hall ended, Phillips went back to Manchester to appear at a fundraiser for an animal shelter. It was held at a bar on the bottom floor of a converted cotton mill on the banks of the Merrimack River. He spent time behind the bar serving drinks to customers who seemed mildly bemused by the spectacle as his ever-present camera crew tried to capture footage.

The bar’s owner, Peter Telge, is a supporter of Phillips’s candidacy. He told Vox he thought Biden, whom he supported in the past, was physically “failing.” Telge added, “It’s nothing against him. He’s a good guy. And most of the things he has done are okay, but I’m not really comfortable with him.”

He said of Phillips, “My wife likes him. I like him. Just to be honest, I’m not sure he has a chance, which I think most of the country feels the same way I do. They want to see somebody have a chance. And so they can come up with a lot of stuff in the next six weeks, eight weeks.”

After Phillips’s stint bartending, Telge did his best to give him a chance and took him around introducing him to customers. He introduced the Minnesota congressmember to a clutch of teachers celebrating the start of winter break with drinks. “This gentleman is running for president,” Telge told them. “Hopefully you’ll vote for him.”

“Hey, everybody. I’m Dean Phillips,” said the candidate. “I’m running … I’m a congressman from Minnesota running in the Democratic primary.” When one teacher commented that she had seen one of his television commercials, he replied, “That’s awesome. That someone saw the commercial.” He then touted his record in Congress to them. “I’m a big full funder of IDEA [Individuals with Disabilities Education Act], just so you know.” The response was dead silence, though Phillips got some laughs with his follow-up line: “I thought that would get a little more reaction.”

It’s not clear Phillips or his team are ready for prime time

The exchange was an indication of just how far Phillips has to go as a candidate. He had gotten into the race only weeks before this event. He announced only hours before the New Hampshire filing deadline, simply by showing up at the State House surrounded by a posse of national reporters. Phillips’s announcement came late enough in the campaign season that he missed the deadline to file to run in Nevada and was forced to scramble to get on the ballot in a number of other states.

His campaign was initially helmed by Steve Schmidt, the former John McCain aide turned Never Trumper who left the Lincoln Project amid allegations that he covered up sexual misconduct. Schmidt soon moved over to a campaign super PAC and was replaced at the helm by Jeff Weaver, a former top aide to Bernie Sanders, and by Zach Graumann, a close Andrew Yang confidante.

The Phillips campaign used a Residence Inn in Manchester as a de facto dorm. Staffers gathered for the free continental breakfast and discussed the basics of how New Hampshire worked. One learned that, when it came to the state’s media markets, “It’s not all Boston — there’s WMUR.” (New Hampshire has a single local television station, which is an ABC affiliate. Otherwise, all local television news comes from Boston.) Stray hotel guests got to see Phillips sign petition papers before his campaign film crew as they dined on hotel scrambled eggs and a sole bodyguard watched from across the breakfast nook. In the hotel parking lot, a converted milk truck, which Phillips made a totem of his 2018 congressional race, sat motionless for days.

The growing pains were apparent when a reporter at the Nashua event asked about an initial pledge made to do 120 town halls in New Hampshire and Phillips’s relative lack of progress toward that goal. He conceded, “I’m gonna tell you, the truth is my first sherpa, if you will, in New Hampshire, who is no longer with the campaign, made that announcement based on John McCain’s 120 town halls,” in reference to Schmidt. “I never stood a chance of doing that in that amount of time. I’ll just be forthright with all of you. That was wrong to announce. There’s no way I could have done it. I’m doing as many as I possibly can. But setting the number was stupid. I own it because it starts and stops with me.”

More signs of struggle were evident during a campaign canvassing operation that consisted of one staffer and one volunteer. It was on the west side of the city, a blue-collar neighborhood with few sidewalks and quite a few triple-decker houses. As the thin twilight of the winter solstice quickly turned into a damp, cold, and cloudy night, a familiar pattern emerged.

Tromping through the cold, the campaign staffer would knock on a voter’s front door and then step 15 feet back, at times almost out of sight of the doorway. Then, with a glance at the phone to create a sense of nonchalance, the staffer would wait for the voter to emerge and tentatively ask their name. The brief acknowledgement would come and the staffer would launch into his pitch.

“Hi, we’ve just been talking to neighbors about Dean Phillips for president. He’s running because most Americans want another option. Seventy-five percent of Americans don’t want the current or the former president to run. And he launched his campaign just a few weeks ago. And he’s already at 15 percent of the polls. Do you have any idea why he might be so popular?”

Some were befuddled, though there were some bites, particularly once it was mentioned that Phillips supported Medicare-for-all — a policy that he had endorsed hours earlier in the pages of Politico, which didn’t seem to be a publication with a major following in the neighborhood.

One voter was enthused, citing her positive experience with Medicare. “It’s a fabulous health plan. Yeah, I was on Medicare when I was pregnant. They were phenomenal,” she said as her toddler screamed for her in the background.

One impediment to all of this, though, was that there was no campaign literature. They had run out and were not expecting a fresh shipment for another week. The result was that there was nothing to hand out, and at houses where nobody answered the door, the campaign left no trace at all.

Sourse: vox.com