Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), who’s running for president, unveiled a new, aggressive criminal justice reform proposal over the weekend that would make it easier for people, particularly those older than 50, to get an early release from federal prison.

The Matthew Charles and William Underwood Second Look Act, first reported by Leigh Ann Caldwell for NBC News, would let people who have served more than 10 years in prison petition a court for early release. Inmates 50 or older would get the presumption of release if they petitioned — so judges would need to show that the inmate is an actual threat to society to keep them incarcerated.

The bill is named after William Underwood, a 65-year-old federal prison inmate currently serving life for drug-related charges, and Matthew Charles, the first person released from federal prison under the First Step Act, a criminal justice reform bill Booker supported and signed into law by President Donald Trump. Charles called for a proposal similar to Booker’s in a Washington Post op-ed.

The proposal is part of a long history of supporting criminal justice reform for Booker. He recently unveiled a clemency reform plan that would, without Congress, provide an early release as many as tens of thousands of federal inmates. Booker has also been one of the most outspoken US senators for legalizing marijuana and scaling back mass incarceration.

But Booker’s new proposal is one of the most aggressive yet, taking direct aim at life imprisonment and mandatory minimum sentences imposing decades in prison. It also wouldn’t include an exclusion for violent crimes, potentially giving a path to early release for people serving time for violent offenses. (Booker’s staff told NBC News it would be harder for those convicted of violent crimes to get a reprieve since it would be easier for a judge to demonstrate that they are a threat to society.)

Those same qualities would, however, likely make it very hard to pass through Congress, which struggled for years to pass criminal justice reforms even for low-level, nonviolent offenses, and only passed the First Step Act as a compromise after years of debate and negotiation.

Still, there’s a good argument for Booker’s bill — and against life sentences more broadly: the age-crime curve. Based on studies and other empirical evidence, people generally age out of crime. This basic fact makes it very unlikely that someone who gets out of prison at 50 or older, even those previously guilty of violent crimes, will reoffend.

In an era in which progressives are taking aim at what they call a racist war on drugs and other policies that have made the US the world’s leader in incarceration, plans like Booker could help make a serious dent. And the underlying concept for it is grounded in decades of evidence.

Why life sentences are unnecessary: People age out of crime

The age-crime curve shows that people tend to age out of crime. In their mid- to late teens and early 20s, people are much, much likelier to commit a crime than they are in their 30s and especially 40s and on.

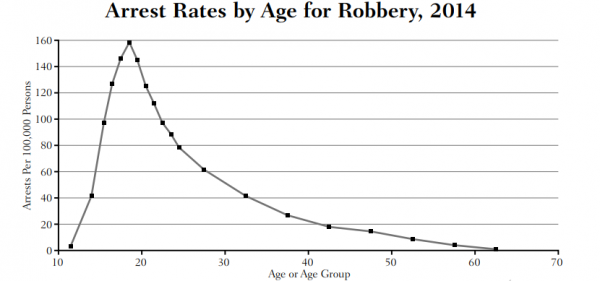

Here’s the age-crime curve for robbery in 2014, taken from The Meaning of Life: The Case for Abolishing Life Sentences by criminal justice reform advocates Marc Mauer and Ashley Nellis:

As the chart makes clear, a person’s propensity to commit a crime — in this case, a robbery — is at its highest around 20 years old. But it drops quickly after that. In his 30s, a person’s chances of committing a robbery drop to 25 percent of what they were at 20. In his 40s, the chances drop to less than 12.5 percent. In his 60s, the risk nearly vanishes.

There are exceptions, like lifelong serial killers. But they’re few and far between.

Virtually no one in criminology disputes the age-crime curve. Nancy La Vigne, vice president of justice policy at the Urban Institute, previously told me it’s “pretty well established in the literature.”

This shouldn’t come as a surprise to most people, particularly those already in their 30s, 40s, or above. Think about how likely you were as a teen to break the law, with underage drinking, using illegal drugs, shoplifting, getting into fights, and so on. Now think about how likely you are to do that today, assuming you’re older. Regardless of whether you got caught in your teen years, you are likely an embodiment of the age-crime curve.

John Pfaff, a criminal justice expert at Fordham University and the author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, previously told me there are a few reasons for the age-crime curve.

“Some of it is physical and hormonal: Testosterone levels go up, testosterone levels go down; violence goes up, violence goes down. Some of it is purely physical: Even if I was as aggressive now as I was 20 years ago, I’m 44 — things are slow, things ache a bit more,” he explained. “But some of it is also social: Getting married is a pathway out of crime; finding a career is a pathway out of crime. So the longer we keep people in prison, the longer we tend to undermine the ways these people mature and age out of crime as they get older.”

Other evidence backs this up. In 2017, David Roodman of the Open Philanthropy Project conducted an extensive review of the research on longer prison sentences. He concluded that “tougher sentences hardly deter crime, and that while imprisoning people temporarily stops them from committing crime outside prison walls, it also tends to increase their criminality after release. As a result, ‘tough-on-crime’ initiatives can reduce crime in the short run but cause offsetting harm in the long run.”

In short, longer prison sentences can actually make people more likely to commit crimes in the long term.

At the same time, locking people up for long periods of time is very costly. There’s the actual financial cost of putting people in prison, which the Prison Policy Initiative estimated at $182 billion for the US in 2017. There’s also the social cost of people being ripped away from their families and communities; as one example, the New York Times calculated in 2015 that for every 100 black women not in jail or prison in America, there are only 83 black men — what amounts to 1.5 million “missing” men who can’t be there for their kids, family, or community while incarcerated.

It’s these kinds of costs, along with the evidence that long prison sentences are ineffective, that’s led some criminal justice reformers, including Booker, to propose limiting if not totally ending life imprisonment.

For more on this topic, read my case for capping prison sentences at 20 years.

Sourse: vox.com