You might think that right now is not a good time to make it easier for predatory lenders to take advantage of people and trap them in impossible-to-escape debt cycles. And yet.

The United States is in the midst of an unprecedented economic moment. Millions of Americans have lost their jobs, and many facets of the economy have been slowed and shuttered as the result of a pandemic. And while the federal government has taken some measures to stem the damage — expanded unemployment insurance, forbearance on mortgages and student loans, eviction moratoriums — much of that support has dried up or is about to.

People are facing a period of nearly unprecedented uncertainty, and a series of recent decisions from financial regulators is making it easier for those in need to be drawn into a spiral of debt that they can’t pay off. Regulators have loosened restrictions around small-dollar, high-interest loans, giving vulnerable people more access to loans that will cost them money they don’t have and allowing outfits such as payday lenders to send money to borrowers without checking whether they’ll ever be able to pay that money back.

“It is shameful that some of the regulatory changes that the agencies have made under the Trump administration have made it easier for lenders to take advantage of people in difficult and really unprecedented circumstances,” said Jeremy Kress, an assistant professor of business law at the University of Michigan. “When people are desperate, some lenders will take advantage of that desperation.”

It’s yet another way the pandemic could disproportionately take a toll on those already at a socioeconomic disadvantage, especially as other supports run out.

No possibility of paying back, no problem?

It’s no secret that the Trump administration has taken a deregulatory approach to most issues, including in banking, finance, and consumer protection. And right now, some of those maneuvers are going to put people in financial situations that are extra precarious.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), a government agency meant to protect consumers, was born out of the financial crisis and brought to life by the subsequent Dodd-Frank Act. The point of it is to protect ordinary Americans from bad actors in the financial system. But under President Donald Trump, it has been weakened, and consumer protection advocates warn that the pandemic could make the situation even worse.

“Instead of saying you should make sure this loan doesn’t put them under, now they’re saying, you should just charge whatever you want”

One of the biggest blows to the CFPB’s accomplishments pre-Trump came in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak in July, when it completed the rollback of a payday lending rule meant to protect vulnerable borrowers from getting sucked into debt. The rule was supposed to make payday lenders follow the same rules as banks checking that the person they lend the money to is able to pay that money back. It would also limit lenders to two attempts to pull money out of borrowers’ accounts.

“Instead of saying you should make sure this loan doesn’t put them under, now they’re saying, you should just charge whatever you want,” said Linda Jun, senior policy counsel at the consumer advocacy group Americans for Financial Reform.

What payday lenders typically do is they lend people relatively small amounts of money that the borrower will theoretically be able to pay back by the time the next paycheck comes in. But the problem is, that’s often not what happens: The loans have high interest rates on them, meaning they’re expensive, and by the time the borrower gets the money in their bank account from their job to pay it back, they’ve got another stack of bills piling up.

According to a 2013 report from the CFPB, a $350 loan can come with a fee of $15 to $100, which for a two-week loan translates to an annualized interest rate of 391 percent. The bureau also found that more than three-quarters of payday loans are rolled over to another loan within 14 days. A 2012 report from Pew Charitable Trusts estimates that 12 million American adults use payday loans each year and that, on average, borrowers take out eight loans of $375 each — and spend $520 on interest.

The problem is, millions of people in the country have no choice but high-cost loans. A quarter of Americans are unbanked and underbanked, meaning that when it comes to sources of loans and just day-to-day banking activity, they don’t have a lot of options. One of the best solutions to this problem to enter into the policy conversation recently is postal banking, but the amount of political will behind such an initiative is unclear.

When the CFPB’s payday rule was first proposed in 2016, it was put forth as a way to end debt traps, and when the proposed rule was put forth in 2017, consumer advocates applauded it. “Payday lenders don’t make their high profits on ordinary small-dollar loans. The big bucks come from trapping a portion of the borrowers in a cycle of debt that crushes families and sucks money out of communities that can least afford it. The CFPB’s new rule will stop these abuses and, once again, help level the playing field for all families,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) said at the time.

But the industry pushed back against the rule from the get-go, and under the Trump administration, it found a friendly ear. The final rule never even took effect before it was rolled back under CFPB Director Kathy Kraninger.

Before the pandemic hit, the bureau was also looking at changing a rule around the types of practices debt collectors can engage in — you know, the ones that harass people once they’ve given up hope of repaying the loans they might not have been able to afford.

The proposed rule would limit collectors to calling a borrower seven times a week but would allow them to send unlimited texts and emails to them (though they would receive instructions on how to opt out). The rule hasn’t been finalized. “It’s probably gotten politically harder to finalize a rule that makes it easier for debt collectors to go after borrowers right now,” Kress said. “As bad as things are today for borrowers, they would have been worse if the CFPB had already finalized this debt collection rule.”

Beware of the bank

The alphabet soup of government regulators making life easier for lenders and harder for consumers goes beyond the CFPB. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), both bank regulators, have taken steps that advocates say have a similar effect.

In 2017, just as the consumer bureau was finalizing what was supposed to become the payday lender rule, the OCC rescinded one of its rules meant to make it harder for banks to make deposit advances. Deposit advances are small, short-term loans that are pretty similar to payday loans — they cost a lot, and they often lead to repeat borrowing because people can’t pay them off. In effect, the move lets banks engage in payday-style lending.

This summer, the OCC and the FDIC began to open the door to so-called “rent-a-bank” agreements that are meant to skirt caps states put on loan interest rates. The legal ins and outs of the issue are complicated, but states generally have in place usury laws that dictate how much interest can be charged on a loan.

Banks are exempt from those laws and can basically charge whatever they want, but nonbanks, such as payday and many up-and-coming online lenders, aren’t and can’t. Rent-a-bank agreements are a way around that because they let high-cost lenders route loans through banks to states where they would otherwise be illegal. The bank handles the loan with the customer and then sells most of it back to the payday lender.

In March, the Wall Street Journal laid out the example of California, which has cracked down on high-cost lenders, short-term lender OppLoans, and its partner bank:

Regulators are now making it easier for such agreements to happen. “The bottom line is that the OCC and the FDIC are siding with predatory lenders that are laundering their loans through banks to get around these interest rate limits,” said Lauren Sanders, associate director of the National Consumer Law Center.

State attorneys general are pushing back against small-dollar, high-cost lenders and against rules and regulations they say enable them. In July, state attorneys general from California, Illinois, and New York filed a lawsuit challenging the OCC’s rule that would exempt high-interest loan buyers from state interest rate caps, and in August, eight state attorneys general filed a lawsuit challenging the FDIC’s rule that would accomplish the same.

“Preying on consumers in financial distress is bad enough. But giving these predatory lenders the key to evade the law meant to protect consumers is despicable,” said California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who has been one of the leaders on both lawsuits.

Becerra’s office says they expect more deregulatory action out of federal regulators in the months to come that will be harmful to consumers. “To see federal agencies ignore the power they have to protect people across the country is both disheartening and a call to action for California,” an adviser to Becerra said.

“We need to be helping people who are struggling right now and not throwing an anchor around their necks,” Saunders said.

“People who are already in vulnerable situations are more vulnerable”

Low- and moderate-income people, and particularly women and people of color, have been hit hard by the pandemic. The country has seen huge job losses and, in turn, losses of income. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, or the CARES Act, the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill the president signed into law in March, did a lot to keep people afloat for a while during the pandemic — it tacked an extra $600 a week onto unemployment insurance through July and entailed a $1,200 stimulus check to most Americans last spring. But now much of the stimulus has dried up, and people still have bills to pay. They’re going to have to figure out a place to turn.

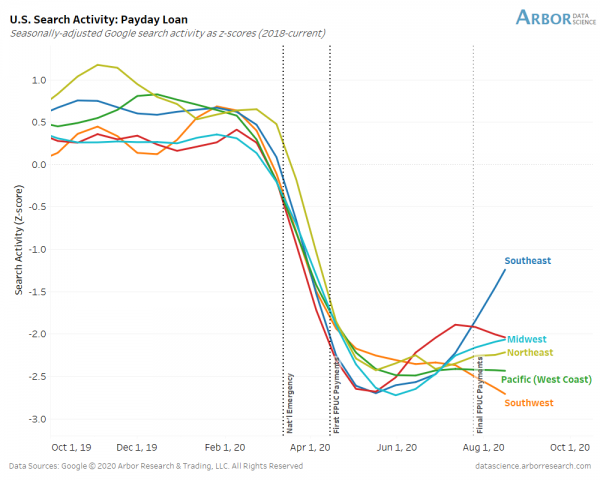

According to Google search data compiled from Ben Breitholtz, a data analyst at Arbor Data Science, payday and installment loan searches are at a lower level than in past periods of stress. But the data shows an uptick in search activity across the Southeast as expanded unemployment benefits came to end in July.

Part of the explanation may be that, even with federal regulatory regulations, many states have cracked down on payday lending, and some have even outlawed such institutions altogether in recent years. But there is likely more to it.

“Lack of paychecks for many given the environment [is] likely the culprit,” Breitholtz explained, noting that as more people come back into the workforce, the situation could change. Unemployment insurance and stimulus checks may have also kept people from needing to resort to emergency loans — in April, household incomes and personal savings actually increased.

“Lenders have no business making loans to people if the lender can’t make a reasonable and good faith determination that the borrower has a reasonable ability to repay the debt”

The issue of how people stay afloat during the current crisis is both a personal one and a collective one. Being saddled with debt isn’t good for the individual. “People who are already in vulnerable situations are more vulnerable,” Jun said.

A lot of people in debt they can’t repay isn’t good for the country, either, whether it’s from a payday lender, on their mortgage, or otherwise. “This isn’t just a matter of consumer protection, it’s a matter of safety and soundness regulations,” Kress said. “Lenders have no business making loans to people if the lender can’t make a reasonable and good faith determination that the borrower has a reasonable ability to repay the debt.”

It speaks to the risks of financial deregulation at large. “A lot of this regulation doesn’t get a lot of attention because it’s a delayed effect,” said Mehrsa Baradaran, a professor who specializes in banking law at the University of California Irvine. Once the situation becomes unsustainable to the point anyone really notices, it’s too late, which is what happened the last time around. “We’re like, what happened?”

There aren’t always easy answers on what people in a tough financial situation should and shouldn’t be able to access — if it’s between feeding your family and winding up with a series of loans you can’t pay, who wouldn’t go to the former? And high-cost loans are hardly the only way consumers lower on the wealth scale find themselves disadvantaged by the system. In 2018, financially underserved consumers spent $189 billion in fees and interest on different financial products, including on overdraft fees and at pawn shops. Until the country thinks of better ways to give people who need loan options — or to get them money directly — this is a cycle Americans are going to be stuck in not only as individuals but as a nation.

“One of the great ironies in modern America is that the less money you have, the more you pay to use it,” Baradaran wrote in 2015. And under the Trump administration, it’s becoming easier for predators to take advantage.

New goal: 25,000

In the spring, we launched a program asking readers for financial contributions to help keep Vox free for everyone, and last week, we set a goal of reaching 20,000 contributors. Well, you helped us blow past that. Today, we are extending that goal to 25,000. Millions turn to Vox each month to understand an increasingly chaotic world — from what is happening with the USPS to the coronavirus crisis to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work — and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com