Andrew Prokop is a senior politics correspondent at Vox, covering the White House, elections, and political scandals and investigations. He’s worked at Vox since the site’s launch in 2014, and before that, he worked as a research assistant at the New Yorker’s Washington, DC, bureau.

The Russian trolls were overhyped.

That’s the implication from a new study in Nature Communications, written by a team of six academics who tried to assess whether the Russian government’s Twitter propaganda effort during the 2016 campaign actually changed users’ minds. “We find no evidence of a meaningful relationship between exposure to the Russian foreign influence campaign and changes in attitudes, polarization, or voting behavior,” the authors wrote.

This isn’t a surprise to me — I’ve long believed the Russian troll farms had little impact. But with the afterlife of the Trump-Russia scandal remaining fiercely contested — with many on the right and some “heterodox” leftists continuing to question whether Russia did anything at all of significance — it’s worth looking back and taking stock of what the Russian government did do that year. Because it wasn’t nothing.

Basically, the Russian government tried to intervene in the 2016 election, and it did so in two main ways.

First, there was that social media propaganda effort: the Russian trolls. On Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, Russians posed as Americans and posted content designed to inflame US political tensions, often attacking Hillary Clinton and supporting Donald Trump. This happened, and it was rather unusual, but as this new study corroborates, there’s no convincing reason to believe it made any difference to Americans’ voting behavior. The Russian propaganda was just some more drops in an ocean of media and social media messaging that Americans were swimming in.

Second, and more consequentially, there were the stolen emails: the hack-and-leak. Russian intelligence officers hacked and obtained emails and documents from many top Democrats and had those put out publicly — giving some to WikiLeaks, providing others to reporters, and posting more on websites they controlled.

These hacks and releases did make an impact — notably, they were a negative story for Clinton that simmered throughout the last month of the campaign. But did they swing the election? That is, in a counterfactual world with no Russian interference, would Clinton have won? My assessment is “probably not,” but it’s difficult to conclusively say for sure.

Still, these interventions were quite unusual in the context of American elections; it was appropriate to treat them as a big deal and understandable that Americans might resent Russia trying to swing their votes. There were real victims here, in the people who saw their private correspondence dumped on the internet, and it’s certainly important to deter interventions like this from happening in the future.

The Russian trolls didn’t swing the 2016 election

The Russian social media propaganda effort was carried out by the Internet Research Agency, an organization based in St. Petersburg and funded by Yevgeny Prigozhin — a Russian oligarch close to Putin who also heads the Wagner Group (a paramilitary group active in the Russia-Ukraine war). The IRA is not officially a government agency, but a bipartisan report from the Senate Intelligence Committee concluded that “the Russian government tasked and supported” its 2016 election interference efforts.

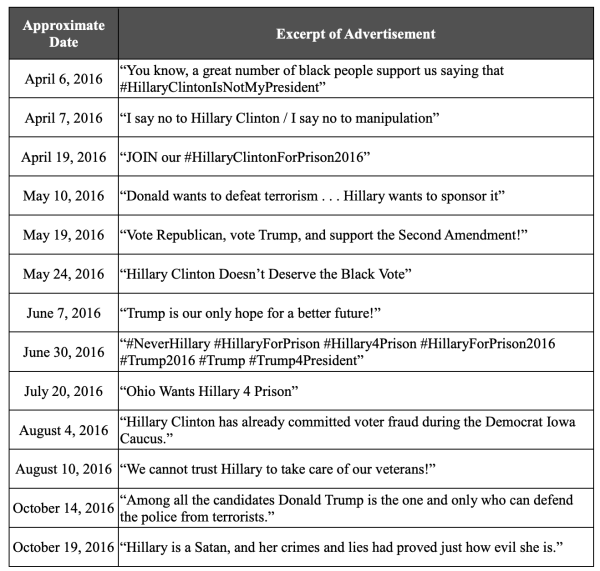

Employees of the IRA created online accounts, claimed to be American, and posted inflammatory or trollish material about US politics. Much of this material was rather crude or silly, but the overall thrust was clear: It tended to praise Trump and attack Hillary Clinton. The IRA also paid for online ads featuring the following pro-Trump, anti-Clinton messaging, as seen in this table from an indictment brought by Robert Mueller’s team, which was tasked with investigating Russian interference with the election:

All this was the source of much fascination and media attention when news of it emerged after the election. Facebook estimated that IRA messaging reached as many as 126 million people on their platform, which certainly seems like a big number. “It leaves all of us who use social media to keep up with friends, share photos and follow news wondering: How’d the Russians get to me?” the Washington Post’s Geoffrey Fowler wrote in November 2017.

But there were always solid reasons to doubt that the IRA posts had much of an impact, despite those scary numbers. If I scroll through Twitter for just 15 minutes, I could be “reached” by messages from hundreds of sources, if not more. I’ll use the metaphor again that these were drops in an ocean: Americans were swimming in messaging about the 2016 election from all sorts of traditional media and social media sources for months (as well as the campaigns and their ads), and there was no reason to believe Russian posts or ads had extra-special persuasive powers that all those other messages lacked.

Now, the authors of the Nature Communications study — Gregory Eady, Tom Paskhalis, Jan Zilinsky, Richard Bonneau, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua A. Tucker — have conducted their own analysis driving this home. Back in 2016, they surveyed nearly 1,500 US Twitter users at various points in the campaign, returning to those same respondents to track how their opinions changed. They also analyzed all the Twitter accounts those respondents followed to see how many were exposed to Internet Research Agency content.

Overall, they found that 70 percent of exposures to IRA posts were concentrated among 1 percent of their respondents, and those respondents were mostly highly partisan Republicans who already liked Trump. That makes sense, given what we know of social media — if you go looking for anti-Clinton, pro-Trump content, that’s what you’ll find, either due to algorithmic recommendation or the accounts you follow simply retweeting messages they agreed with without knowing too much about who was saying them. And that’s the sort of content the IRA was providing. But the finding suggests the IRA messaging was not finely calibrated to target wavering swing voters.

The authors also put the exposure to this messaging in perspective by finding that users had far more posts from traditional media and politicians in their timelines than Russian trolls — an “order of magnitude” more, they write. And ultimately, their survey results “did not detect any meaningful relationships between exposure to posts from Russian foreign influence accounts and changes in respondents’ attitudes on the issues, political polarization, or voting behavior.”

Now, it is true that this is just a study of Twitter posts and not other social media platforms like Facebook where the IRA was also active. The overall logic is sound, though. Americans can certainly resent the Russian effort to propagandize their views, and Mueller’s team argued that much of what they did violated US laws. But the Russians didn’t have some magically effective messaging that warped Americans’ minds and forced them to support Donald Trump.

The hack-and-leak was a bigger deal (but still may not have swung the election)

In 2016, the GRU, Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency, went on a spree of hacking of Americans involved in politics or government.

Using simple spear-phishing emails (links to a fake Google page that asked people to enter their password), they obtained access to the email accounts of Clinton campaign chair John Podesta, as well as several Clinton staffers, volunteers, and advisers. According to the Mueller report, they spear-phished an employee of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which got them credentials for access to the DCCC computer network and eventually the connected Democratic National Committee network. The hackers then used malware to scoop up emails and documents.

(Some critics of the Russia investigation like journalist Matt Taibbi still purport to be skeptical that the hacks were the Russian government’s doing, but Mueller’s report and his indictment of 12 Russian intelligence officers provide a wealth of specific detailed allegations about exactly how these hacks happened and which specific officers and units in the GRU were responsible. This is inconvenient for the Russiagate skeptics, so they tend to ignore it.)

Foreign hacking is far from unusual; the Chinese government, for instance, was said to have hacked Barack Obama’s and John McCain’s presidential campaigns in 2008, and the US has likely done a fair amount of it as well. The jarring departure was what happened next: The stolen information began showing up publicly, in massive accounts. (Another unusual aspect was that one major candidate openly welcomed this intervention, with Trump publicly urging Russia to “find” more Clinton emails.)

The GRU used the persona of “Guccifer 2.0” (“Guccifer” was a name used by a jailed Romanian hacker) and registered a website, DC Leaks, posting hacked material there and providing some to reporters. But two specific batches were saved for WikiLeaks, a nonprofit that had posted leaked US government material in the past.

First, in late July 2016, just before the Democratic National Convention, WikiLeaks posted thousands of DNC emails and revealed that many DNC members privately spoke of Bernie Sanders with disdain. The revelations drove DNC Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz and other top staffers to resign, and overall made an ugly start for the Democratic convention.

Second, in early October 2016, WikiLeaks began posting Podesta’s emails — and would continue to post them, in batches, up through the election. The Podesta emails weren’t as explosive, but in anyone’s private email there will be embarrassing material they’d prefer to keep private, and if that embarrassing material is only being released about one candidate, there could be an impact. So each new release drove some media coverage, and they were touted constantly by Trump on the campaign trail, who often baselessly claimed they revealed some malfeasance or another.

Trump sank in the polls for the first half of October, as controversy over his Access Hollywood tape hit the news. In the second half of the month, the news cycle moved on and his poll numbers rebounded. He didn’t pass Clinton in the polls, but he got closer — close enough to pull out a win by less than 1 percentage point in three key swing states.

Yet I would be hesitant to claim that the drip-drip-drip of Podesta email coverage was responsible for Trump’s recovery. Part of it could simply be about Republican partisans briefly turned off by his scandals “coming home” to him before the election — a process that may have unfolded even if there had been no Russian interference. (Trump improved in the polls in the last half of October 2020, as well.)

The case could be made that, simply by keeping the words “Clinton” and “emails” in the news for a month, the Podesta releases hurt her campaign (since any coverage of the leaks would remind voters of a separate matter, the FBI investigation into Clinton’s emails). Still, it’s far easier to make the case that FBI Director James Comey’s late October letter saying new Clinton emails had been discovered changed the outcome, as Nate Silver has argued, than the Russian hack-and-leaks. The Comey letter was a discrete event that dominated headlines and preceded a sharp change in the polls, while the Podesta leaks were one of many stories simmering in the background throughout October.

So I’ve never been persuaded that Russia fully got Trump elected. That is a high bar, though, and despite the overhyped Russian trolls, it seems to me the hack-and-leak was a consequential intervention that damaged Clinton and the Democrats to some extent. And it really was an attempt to affect Americans’ votes and hurt a presidential candidate who Russia didn’t like — an attempt that violated US laws against hacking and disclosing campaign activity. The intervention was real, the investigation into it was justified, and the anger at the Russian government for what it tried to do is justified as well.

Sourse: vox.com