Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

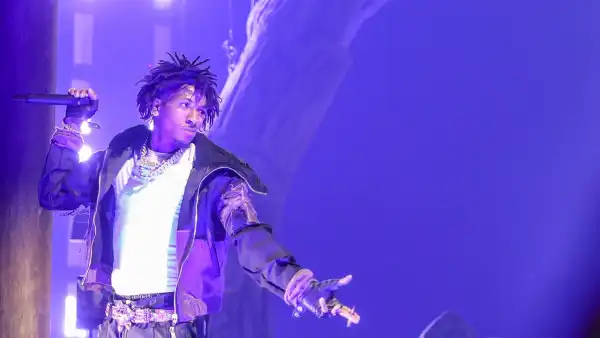

Few recent music happenings have generated as much anticipation for potential pandemonium as this one: the inaugural major headlining tour of YoungBoy Never Broke Again, a rapper of distinct force and skill, recognized by his remarkably young and rambunctious admirers as NBA YoungBoy. The tour commenced last month, with a duo of sold-out performances at the American Airlines Center, in Dallas, home to the Mavericks; swiftly thereafter, footage of ebullient attendees began to spread online. The exhilaration hasn’t been uniformly positive: during a show in Kansas City, a fourteen-year-old concertgoer was filmed attacking a sixty-six-year-old usher, leading to charges of felony and misdemeanor assault; scheduled dates in Chicago and Detroit have been called off, with scant explanation. Yet, upon the tour’s arrival at the Prudential Center, in Newark, the atmosphere was joyous, albeit disorderly. The venue teemed with devotees donning black YoungBoy T-shirts and brandishing slime-green YoungBoy bandanas: they disregarded the seating, congested the passageways, and recited every lyric. The only individual who seemed untouched by the fervor was the composed and rather stately presence who sparked it. YoungBoy made his introduction from within a coffin that was lowered onto the stage, and he delivered his verses with the sadness and resolve of a person aware that, ultimately, he would return to his point of origin, but no longer upright.

At the outset of YoungBoy’s journey, he appeared fearless. “Don’t address me like I’m immature,” he scoffed, in a song released in 2015, when he was merely fifteen. He possessed a lean build and a stern demeanor, marked by indentations on his forehead resulting, as he later clarified, from a halo brace that had been screwed into his skull after fracturing his neck while wrestling with friends at age four. He also exhibited fierce devotion to his city, Baton Rouge; in the visual accompaniment for “Murder,” from 2016, he and his associates posed in a modest abode, displaying modest sums of money and plentiful firearms. His delivered lyrics—“That stuff you’re saying doesn’t intimidate us / Forget your approach, you won’t see us”—were noteworthy due to his distinct Louisiana drawl, and his transition between lively rapping and a melancholic wail that hinted at reservations beneath the bluster. “I’m scared of others, and quite timid,” he confessed, in a hushed tone, during an exceptional 2023 video conversation with Billboard. “People are heartless. It’s as if we lack self-control.”

Over the preceding decade, YoungBoy has put out a staggering volume of tracks: exceeding thirty-six complete albums, including eight in 2022 alone. Simultaneously, he has cultivated a substantial internet following, notably on YouTube, without experiencing a mainstream smash; “Make No Sense,” from his acclaimed 2019 album “AI YoungBoy 2,” reached No. 57 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, but has amassed over half a billion streams on Spotify. Hip-hop triumphed globally decades ago, yet the presentation in Newark served as a reminder of the genre’s incomplete assimilation, attributed in part to its unique connection to underserved Black communities akin to YoungBoy’s upbringing. Despite his widespread recognition, he maintains limited affiliations with the wider sphere of popular music, imbuing the performance with both the closeness and zeal of an underground assembly. Green lights illuminated the platform, and the audience echoed YoungBoy’s lyrics, consistently illustrating the potential for unyielding determination to dissolve into vulnerability: “They’re constantly attacking me, I compete to win, they’re intimidated by me / I can’t hardly—can barely find rest, or even draw breath.” He has a talent for verses that are strikingly revealing, at times in multiple senses at once.

Numerous individuals consuming YoungBoy’s unending output of new music are concurrently absorbing accounts of his various confrontations and judicial proceedings. At seventeen, he faced allegations of involvement in a drive-by shooting. (He entered a guilty plea for aggravated assault with a firearm, receiving a suspended sentence.) At eighteen, he stood accused of assaulting and abducting his then-girlfriend, a claim seemingly supported by surveillance recordings. (He pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and received probation.) He has engaged in feuds with various rappers, several of whom were later victims of fatal shootings, and while YoungBoy has never been formally implicated in these fatalities, admirers have found themselves inclined to presume that the threats within his verses mirror actions he has truly committed, or might perpetrate in the future, should his numerous adversaries fail to exercise caution. By the time the Billboard videographer located him, he resided not in Louisiana but in snowy Utah, endeavoring to evade further entanglement: under house arrest, restricted to three simultaneous visitors, awaiting trial on federal firearm charges. He was deemed not guilty in one instance and confessed guilt in another; last December, he was handed a sentence of twenty-three months imprisonment and five years of supervised release, though he secured release from federal detention earlier this year. In May, President Trump issued him a pardon, absolving him of his probationary terms, which may have rendered a significant tour like this untenable. On Independence Day, he unveiled an album titled “MASA,” an acronym for Make America Slime Again. (It constitutes one of three YoungBoy releases thus far this year.) Within hip-hop parlance, “slime” functions as a versatile term of camaraderie, with YoungBoy’s title serving as both an assertion and a Presidential homage. The album lacks some of the sharpness and dynamic energy of his finest work, but it overflows with magnetism and a few unexpected deviations, none more pronounced than “XXX,” which sources its chorus—“Sex and violence!”—from an old punk group called the Exploited, and which incorporates a direct political endorsement. “Whatever Trump’s doing, it benefits the youth,” YoungBoy proclaims, though the rest of the album implies his own continued interest in misdeeds.

YoungBoy’s stage name becomes progressively less fitting with each passing year: he will reach twenty-six within weeks, and he has fathered at least ten offspring with eight distinct women. (A particularly endearing and melodic track titled “Kacey Talk” bears the name of one of his sons, not due to lyrical themes of parenthood, but, as YoungBoy later explained, because he happened to be holding his son during its recording.) In Newark, he appeared transformed by his stretches of confinement and house arrest—less reformed by them than marked by their presence. Aside from the coffin, the foremost stage component consisted of a small house bisected by a zig-zagging horizontal line, enabling it to split open like an immense egg, trapping YoungBoy inside its shell. Within this framework, even a straightforward boast regarding the handling of a Beretta conveyed a sense of sorrow. “I just brandished my ’Retta and tried to halt a rival / I just exited my residence and nearly shot someone,” YoungBoy rapped, within a somber track called “House Arrest Tingz,” perhaps recounted from the perspective of an individual whose antisocial inclinations are exacerbated by isolation.

A facet of this tour has seized the public imagination—over the recent months, YoungBoy’s profile has reached a peak. The streamer Kai Cenat recorded himself witnessing a YoungBoy concert in Los Angeles, shedding a tear during “Heart & Soul,” a form of self-affirmation song wherein YoungBoy calls himself by his given name: “Kentrell, you must mature, you have fathered many children.” (For YoungBoy, as for many hip-hop artists, the intense tracks amplify the impact of the gentle ones.) Football teams have adopted “Shot Callin,” the breakthrough single from “MASA,” to commemorate triumphs. Furthermore, during a recent Apple Music interview, Keon Coleman, a twenty-two-year-old wide receiver for the Buffalo Bills, proposed YoungBoy for a Super Bowl halftime spectacle. The interviewer, the veteran hip-hop radio figure Ebro Darden, fifty, expressed disbelief. “That man is incapable of performing a live show that would entertain anybody,” he asserted, playing the role of hip-hop’s established authority. “He won’t rehearse!”

Coleman affirmed its irrelevance. “He needs neither backup singers, nor dancers, nor camaraderie,” Coleman stated. “He stands alone.”

Actually, YoungBoy enlisted a sextet of dancers, all female, for his Newark performance, though they appeared humorously out of sync alongside the main performer, who displayed minimal movement and rarely smiled, delegating the exhortations expected of hip-hop crowds to his d.j. (“Jersey, I need you to generate some motherfuckin’ noise in the building one time!”) Upon its conclusion, after surpassing two hours, YoungBoy simply conveyed, quietly, “I appreciate your attendance in witnessing me tonight.” He has pledged at least one more album release this year, which numerous individuals will undoubtedly overlook, notwithstanding YoungBoy’s current visibility, but his devotees will surely devour. There exists a sense of wonder in his capacity to imbue rap lyrics with the weight of spiritual testament. Equally astonishing is hip-hop’s enduring ability, after roughly fifty years of existence and chart-toppers, to accomplish precisely this: to identify a troubled yet compelling youth from Baton Rouge, place him on stage—“alone,” or approximating it—and empower millions to rap along. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com