Of all the inexplicable events in Genesis, the story of Noah’s nakedness and its consequences stands alone. It’s an easy story to sum up. Noah got drunk and fell asleep naked; his son Ham saw him. Ham told his two brothers, Shem and Japheth, who, out of respect for their father, walked backward into Noah’s tent, so as not to see him, and put a garment over him. When Noah woke up and found out what had happened, he cursed Ham and his son, Canaan—the father of the Canaanite people, the original inhabitants of what became Palestine—as follows, in the King James version: “Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.”

What is the violation involved in seeing your own father naked? Talmudic commentators thought it most likely that “see” was a euphemism, and that there were three possible crimes at hand—Ham had sex with Noah, or raped him, or castrated him. Medieval Christian theologians argued that Ham’s sin was laughing at his father’s nakedness, although the text in Genesis doesn’t mention laughter. Modern Biblical scholars have never been able to agree on a single explanation, although most agree that the verses were written with a particular purpose in mind: to justify the subjugation of the Canaanites, which at the time of its composition was likely well under way.

The Curse of Ham is perhaps the most vividly destructive story in all of the Hebrew Bible, and not just for the scenes of divinely inspired slaughter in the Book of Joshua, events that reverberate in Israel and the Palestinian territories to this day. It’s had an even more terrible afterlife: since the Middle Ages, in Europe, the Islamic world, and the Americas, the Curse of Ham has been cited as a Biblical justification for serfdom and slavery, partly because Ham and Canaan are associated with darkness or blackness—a myth that begins not in the text of Genesis but in later interpretations, whose origin is still a subject of scholarly debate.

The Curse of Ham is terrifying because it seems so arbitrary. No one can say definitively what Ham did that was so terrible and unforgivable, why the curse was not pronounced on Ham but instead on his son and all of his son’s descendants, or even why Noah, who is not God or even a prophet on the level of Moses, is able to level a command with such destructive, irreparable consequences. It’s also terrifying because, in its arbitrariness, it makes a kind of intuitive sense about fatherhood and masculinity and power.

On the day of the Senate testimony of Christine Blasey Ford and Brett Kavanaugh, I had to drive to the airport in the middle of the afternoon to catch an overnight flight, after a full day of teaching and office hours, leaving me just a half hour to listen to the hearings on the radio. When I tuned in, pulling out of the parking lot, I heard only dead air. Then Kavanaugh began to speak.

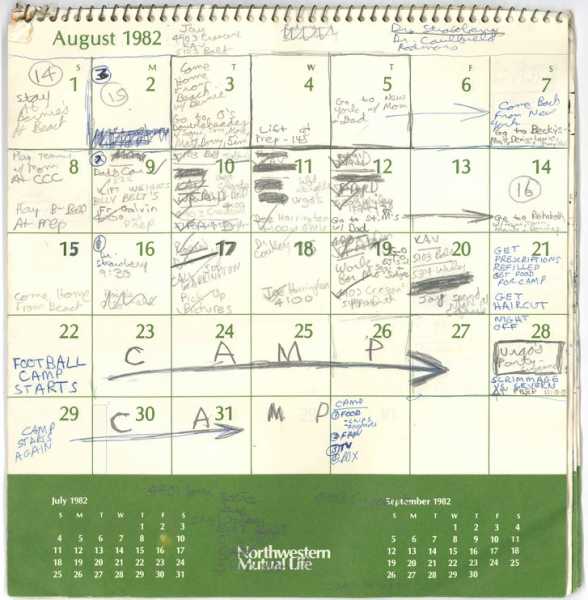

A page from a calendar that Kavanaugh kept in 1982.

Photograph by Senate Judiciary Committee / NYT / Redux

“My dad started keeping detailed calendars of his life in 1978,” he said, and stopped. “He did so as both a calendar and a diary. He was a very organized guy, to put it mildly.” He stopped again, clearly overcome with feeling. “Christmastime,” he said, in a strangled voice, as if gulping for air. “We’d sit around and he regales us with old stories, old milestones, old weddings, old events from his calendars.”

I turned off the radio and drove in silence for a few minutes. Then, out of a sense of obligation—civic duty, I suppose—I turned it on again. I couldn’t see him, yet my impulse was to avert my eyes, or rather, my ears. Kavanaugh was having a breakdown on live radio and TV. He was apparently lying, and lying under oath; he couldn’t possibly be confirmed; it seemed to me that he didn’t want to be confirmed. He wanted to rage; he wanted to turn the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing into a bad simulacrum of a David Mamet play.

DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Well, the difficult thing is that it—the—these

hearings are set and—set by the majority. But I’m talking about

getting the evidence and having the evidence looked at. And I don’t

understand—you know, we hear from the witnesses. But the F.B.I.

isn’t interviewing them and isn’t giving us any facts. So all we have . . .

KAVANAUGH: You’re interviewing me.

FEINSTEIN: . . . is what they say.

KAVANAUGH: You’re interviewing me. You’re—you’re doing it, senator.

I’m sorry to interrupt . . .

FEINSTEIN: Well . . .

KAVANAUGH: . . . but you’re doing it. That’s—the—the—there’s no

conclusions reached.

FEINSTEIN: And—and what you’re saying, if—if I understand it, is that

the allegations by Dr. Ford, Ms. Ramirez, and Ms. Swetnick are—are

wrong?

KAVANAUGH: Yes, that—that is emphatically what I’m saying;

emphatically. The Swetnick thing is a joke. That is a farce.

FEINSTEIN: Would you like to say more about it?

KAVANAUGH: No.

A week later, Kavanaugh was confirmed and immediately sworn in by the Chief Justice, John Roberts. In the two months since the hearings, the country has lurched through at least a dozen more major crises and a midterm election, and has now settled into the grinding business of resisting, or abetting, a 5–4 Supreme Court majority that favors the right.

After a traumatic event, in the short term, life has to go on. (Walter Benjamin, writing in the nineteen-thirties, put it this way: “That things ‘just keep on going’ is the catastrophe.”) This particular perverse continuity is a feature of the Trump era. But I doubt anyone who witnessed the Ford-Kavanaugh hearings has forgotten the sheer emotional chaos—the shouting, the sneering, the mockery, the raw cynicism, the red-faced hectoring and pleading, the “I like beer”—on display that afternoon. Because it was effective, it is now magnified. Politically, if not legally, it represents a new precedent.

After witnessing the testimony, Robert Post, a former dean of Yale Law School, wrote a blog post, later republished in Politico, calling on Kavanaugh to withdraw his nomination. “Judicial temperament is not like a mask that can be put on or taken off at will,” he wrote. “Judicial temperament is more than skin-deep. It is part of the DNA of a person . . . . Judge Kavanaugh cannot have it both ways. He cannot gain confirmation by unleashing partisan fury while simultaneously claiming that he possesses a judicial and impartial temperament.” This is, of course, exactly what Kavanaugh did: he lifted the mask. In his rage, he revealed himself to be an actor, a judge manqué, a plant—a committed partisan, carefully prepared and trained to perform a role, indifferent and even hostile to the very law that he now embodies, beneath his Justice’s robes.

I grew up with an intermittently angry father—one who was loving and kind much of the time, but also given to unpredictable fits of rage. He punished my brother and me with harsh spankings, not often, but often enough. These episodes were always over very quickly and were never discussed afterward; the last one occurred when I was about thirteen, and in the years that followed I sometimes forgot they had happened at all. In the last months of his life, in 2013, I had candid conversations with him about many subjects—but not that. He died without accounting for his violence. I never asked him about it because I understood, without having to articulate it, that worse than the beating itself would be the exposure and the acknowledgment. I didn't have the courage to ask my father try to justify, or explain, or even apologize for what he had done.

Listening to Kavanaugh speak, I could tell within a few minutes that he had never been asked to account for himself—that despite a prestigious education he could not string together two coherent sentences of self-reflection. Confronted with Ford’s testimony, he had no story to tell; he couldn’t utter the phrase “This is how I’ve changed” or “This is what I’ve learned.” Instead he stripped the rhetoric of self-defense down to its most basic layer: I’m right, you’re wrong; she’s lying, I’m not; she remembers nothing, I remember everything. For his supporters, this apoplectic behavior under oath was not only persuasive; it opened up that vein of reflexive empathy that conservatives often reserve for white men in positions of power. The hearing, Trump said afterward, was something “nobody should have to go through,” a phrase repeated over and over in the conservative media, along with much outrage over the violation of Kavanaugh’s privacy and the sanctity of his family and marriage. Opinion polls taken after the hearings showed that many Republican voters saw him as a hero for fighting back—defending his honor against accusations that were devastating, whether or not they were true.

Why is being held accountable—being accused, or exposed, or both—so terrifying under patriarchy? One reading of Genesis proposed by contemporary scholars is that Ham “seeing” Noah isn’t a metaphor or a euphemism at all; the crime is in the gaze itself. Other Near Eastern cultures, these scholars note, viewed the exposure of the male genitals as “inherently feminizing and shameful.” Freud, who based his theory of the primal scene on the trauma of seeing one’s parents having sex, would have probably agreed with this view. The horror of a father’s exposed penis, to Freud, was perhaps self-evident—the kind of horror that, when repressed, can give rise to all kinds of violent or abusive behavior. But what if the horror isn’t repressed? The distinctive quality of Trumpian nakedness, which is also Noah’s nakedness and Kavanaugh’s, is to be brazen and defensive, shameless and humiliated. This variety of the primal scene was televised; in some quarters, including in a narrow majority of the Senate, it was celebrated.

How did we get here? It’s a question posed by a thousand pundits and anxious cultural observers. How did social norms for political behavior change so radically that Trump and Kavanaugh’s performances of naked rage are not only tolerated but celebrated by a significant minority of Americans, and treated by the national media as just another variety of public discourse? The answer, unhappily, is that these social norms of masculinity and whiteness, in fact, have remained largely unchanged in America, but the culture’s compensatory regime of polite avoidance and wishful thinking has now partly—not entirely—dissolved.

This is shocking and painful. It is also instructive. Shem and Japheth, after all, were rewarded for not looking: walking backward, carrying the garment while shielding their eyes. The easy way to restore a sense of order would be to pretend that none of this happened. Barring impeachment or illness, Kavanaugh will remain on the Court for decades—for the rest of many of our lives. Over time, his confirmation could come to seem like a bad dream. But what would happen if people refused to turn away—even if they were cursed for it? What if they kept watching, remembering the mask, remembering the face underneath?

Sourse: newyorker.com