Evenings around the campfire in southern Baja, we’d play music, read from manuscripts, tell stories, and talk about what was next in our lives, or what we hoped would come next.

It was that kind of trip in February of 1994—a group of seven friends of various ages, including my wife, Idoline, and our baby girl, travelling and camping in four vehicles, a month-long vanishing act into the wild to check in with each other and ourselves. The expedition leaders were Chris and Jay Speakman. They’d explored Baja in the nineteen-seventies before spending a decade as commercial lobster fishermen in the Cranberry Islands, off the coast of Maine. I was in between journalism jobs, and my wife and I were in the thick of raising our year-old daughter. Our friend Stephen Hillenburg had driven down from Los Angeles. His hours not surfing were spent sketching in a little pad he carried with him—shells, sea life, shipwrecks in the distance. And he would beachcomb, collecting bits of rope and buoys, and extricating desiccated sea life from the scum line. An unassuming marine biologist with a generous smile who never missed a chance to catch some waves, he’d studied animation at CalArts as a grad student, and was on a break from his job at Nickelodeon.

We surfed and fished and camped from Ensenada to Todos Santos, east around Baja’s southern tip into the Sea of Cortez. The winds howled hard offshore for almost the entire month, but the Pacific kept its end of the bargain, sending solid waves almost every day. Some evenings Steve would play the guitar, and Jay would accompany him on harmonica. One night at our campsite, Steve produced a sketchbook of ideas for a cartoon he wanted to create. We passed it around, a collection of dozens of drawings of a square kitchen sponge in shorts and a funny hat, and a variety of other sea-creature caricatures. He explained that his cartoon would take place entirely in a single tidepool, a tiny undersea universe. The sponge would be the lead character.

“A sponge?” one of us remarked, incredulous.

“Sponges are sedentary, they don’t have features,” we pointed out. “Like eyes and mouths. They’re just blobs that don’t move.”

“Exactly, that’s the gag. A sponge,” Steve replied, clearly unimpressed by such predictable observations. “He won’t just be a sponge. He’s going to be a common kitchen sponge.”

We knew Steve as immensely industrious and creative. He’d made an ingenious comic book about marine life in a tidepool, as an educational aid, when he taught at the Ocean Institute, at Dana Point. He’d won festival awards for two films that he’d made as a grad student at CalArts. His drawings were loose, evocative, fun. He had a quick, easy, uncynical sense of humor. But it’s fair to say that the group around that campfire was generally confident that while Steve, then thirty-two, would likely have a successful career as a cartoonist and filmmaker, his sponge would remain in the pages of that sketchbook.

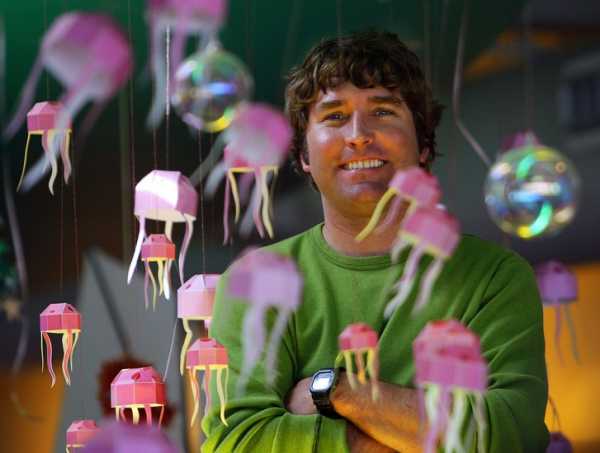

Stephen Hillenburg at Nickelodeon’s offices, in Burbank, California, in 2002. Hillenburg died, of Lou Gehrig’s disease, on Monday.

Photograph by Anacleto Rapping / Los Angeles Times / Getty

I’ve thought about that trip and that moment often. How the spark of an idea can become something huge through a combination of hard work, persistence, and creativity, and the ways we were all dreaming and scheming about our own lives at that time. I remember calling Steve a decade later, in 2003. By then he’d made his common kitchen sponge into the hit cartoon and mega brand “SpongeBob SquarePants.” Over the years we would talk on the phone, but mostly I’d followed him in newspaper and magazine articles. He’d completed three seasons of the cartoon by then, and he was exhausted. He was on his way to South Korea to oversee the animation of the first “SpongeBob” feature film. I joked that all the press had missed the best part of the “SpongeBob” story—his connection to the ocean as a surfer and how he’d shared his earliest sketches with pals on a surf trip to Baja. “You’ll have to tell that story one day,” he replied. I’ve told the little Baja anecdote dozens of times to my two children, who grew up watching the cartoon, and to their friends, and to my own friends. I tell it as a sort of parable: look what can happen when you believe in something, even if others think it is small and odd.

Steve was standing in the middle of his street when I drove up, last July, to pay him and his wife, Karen, a visit. It had been eight years since we’d last seen each other and the person I saw was physically a fraction of the man I’d known. As I approached, he arched his eyebrows and shrugged apologetically, putting out his hands palms up. “No surf,” he said, shaking his head. The cove near his house in Malibu was flat. Then he added, with astonishing earnestness, “I don’t surf anymore. A.L.S. I have A.L.S.”

I’d heard the devastating news that Steve had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, more than a year earlier, when he’d been diagnosed. But I’d been reticent to reach out until I could coördinate a visit. A neurodegenerative disease that atrophies the muscles, A.L.S. eventually impairs mobility and motor function, including speech. For Steve, it had meant a significant loss of muscle mass throughout his body and a decline in his lung function. He understood what was being said and what was happening around him, but his speech came in single, short sentences. He had stopped surfing in 2017, he was able to tell me, and rarely went in the water anymore.

I rode into Malibu on waves of regret. We’d both dropped the ball on our friendship—kids, jobs, family, with lives on separate coasts. Now, with Steve ambushed by A.L.S., I wanted to see him before too much time passed, to meet Karen and their son, Clay, again, and to talk about the places surfing had taken us. I wanted to learn from him, at last, how he pulled off the improbable miracle of “SpongeBob SquarePants.” But it was too late. He was unable to answer those questions himself anymore. The twinkle remained in his eyes, but the words wouldn’t come. Instead, I immersed myself in him in the only way I could. I called on his family, friends, and colleagues. And I went on a “SpongeBob” binge of dozens of early episodes of the cartoon, watching day and night, then the two movies and the hit Broadway musical.

Steve still went to the office every day, so I joined him, fulfilling a wish I’d always had to be in the recording studio with him. “SpongeBob” is created in the brightly painted Nickelodeon offices in Burbank, where doodling on the walls is encouraged and wide-eyed kids trundle through the halls on class trips. The cradle of the “SpongeBob” world seemed improbably sleepy on that Wednesday in July. I’m not sure what I expected, exactly, but it was bafflingly low-key, a dozen or more people quietly working on the next show—the very core of the brand.

There was a touch of sadness in the air, too. People I spoke with kept correcting themselves, catching the past tense in their descriptions of Steve’s guiding and much-admired hand in the show. Almost every conversation was tinged with heartache, and expressions of affection for the man who made it all happen. After that trip in the mid-nineties, Steve began by taking his cartoon idea to a handful of friends he knew from CalArts, plus a few colleagues he’d worked with at Nickelodeon on the cartoon “Rocko’s Modern Life.” He pulled together the core group on the clarity of his concept, his friendship, his collaborative, congenial working style, and, more importantly, his judgment, which many had witnessed on “Rocko.”

“I just knew if Steve was coming with it, it was going to be good and fun,” Allan Smart told me. Smart, who’d worked with Steve on “Rocko,” signed on for the “SpongeBob” pilot, and has been with the show ever since, now working as its supervising director. Steve and his team produced the first season in 1999. Another followed immediately. Initial audience response was solid, but it wasn’t until Nickelodeon began rolling out “SpongeBob” merchandise that everyone realized they had a smash on their hands. “SpongeBob” stuff was selling out in days, and members of the crew and cast were seeing the yellow sponge on everything and everyone, everywhere.

“Suddenly, we realized it was huge. The company couldn’t keep up with demand,” Jennie Monica, who started as Steve’s assistant, in 1998, and is now the producer of the show, said. Within a decade of our Baja trip, “SpongeBob” would become Nickelodeon’s most successful, and lucrative, cartoon and brand. But why? What is it that made it so successful? “That’s the question everyone would like to know the answer to,” Tim Hill said when I caught up with him. A longtime and close friend of Steve’s, and an early contributing writer on the show, Hill is currently directing the third “SpongeBob SquarePants” movie.

I asked this same question of a dozen people close to the cartoon. Any show’s success springs from an intangible alchemy of story, writing, acting, and directing. For example, SpongeBob’s voice actor and a key member of the show’s team from the start, Tom Kenny, is given much credit for the show’s success, as he instantly developed a keen sense of the character he plays. But everyone agrees that the essential magic came from Steve. He wanted simple stories taken from real-life experiences (a yearbook picture gone wrong, how a new fad or neighbor steals the attentions of your best friend, how a good joke overtold can go wrong) and a show with a moral code that reflected earnest sensibilities.

“SpongeBob is not cool, he’s not aspirational,” Hill noted. “He just wants to go to work and be happy. There’s an innocence to him, and that definitely had a winning quality. He sees the good in a horrible person. Steve thought he had a responsibility and was very clear about the moral code,” a code Steve himself seemed to live by—the virtues of optimism, courage, the righteousness of industrial ardor, the importance of triumph over fear and élitism, the value of being in the moment, unfazed by fads. We all love goofy optimists who don’t care what the cool kids think.

Sitting next to Steve in the studio, watching and chuckling as another show came together for the five-hundred-and-something-th time, the obvious occurred to me. Even as Steve clings to this one life, we will all laugh with his sponge, and with him, forever.

That he himself is the immortal SpongeBob is indisputable and often noted. I can’t help but hear Steve in SpongeBob’s glee, and his total lack of interest in grand, scheming ambition. Take the moment in the first “SpongeBob” movie when Plankton exclaims, almost frothing at the mouth, “I’m going to rule the world!”

SpongeBob regards the evil little green organism for a moment and replies, deadpan, “Good luck with that.” That’s Steve.

Two years ago, with Steve beginning to fall ill, a producer from the first movie called Hill and asked him to work with Steve on developing the script for the third “SpongeBob SquarePants” movie. Hill initially recoiled at the pressure the moment seemed to represent. “I didn’t want to be the guy who screws this up,” he told me.

But, over the course of a few meetings, Hill relented and wrote the treatment. One thing led to another and Hill is now the director, which seems fitting.

“The story is nostalgic,” Hill told me. “Steve is actually in the story,” a fitting first for the cartoon.

He paused and added, haltingly, “It’s basically a love letter to the show and to Steve.”

I remembered an exchange on that phone call I’d made to Steve back in 2003. He was by then rich and well known in the animation world. We talked about going to Indonesia together, and I remarked how far he’d come since our dirtbag Baja run.

“Not really,” he laughed. “I’m still just that guy with a wacky idea.”

This piece is an excerpt from an essay titled “The Billion-Dollar Sketchbook,” forthcoming in the February/March issue of The Surfer’s Journal.

Sourse: newyorker.com