Forecasts of societal demise, if for no reason other than their consistency throughout history, always run the risk of making critics appear hysterical and melodramatic. Even so, one can’t help but wonder whether America has lost the infrastructure necessary to support intellectual greatness.

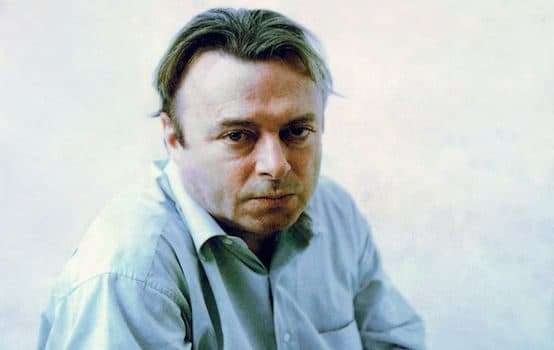

Christopher Hitchens was born, raised, and educated in England, but as an author and polemicist he acquired his most persuasive power and propulsion in the United States. He wrote his most controversial and skillful essays for American publications, authored biographies of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, and became an American citizen at the Jefferson Memorial just a few years before he died of esophageal cancer.

In the introduction to his fifth essay collection, Arguably, he wrote that “the people who must never have power are the humorless. To impossible certainties of rectitude they ally tedium and uniformity.” Under the banner of intellectual exploration, he presented essays on topics as seemingly disparate as the United States Constitution, the literature of Saul Bellow, and oral sex. “An essential element of the American idea,” he noted, “is variety.”

His humbly stated but deeply held conviction on the necessity of argument broadens into a mission statement for aspiring writers: “Still, I like to believe that these small-scale ventures make some contribution to a conversation without limits of proscriptions: the sin qua non of the sort of society that knows to keep the solemn and the pious at bay.”

Since 2011, the year of Hitchens’ death, social media has emerged as dominant in public discourse, and in confirmation of Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” theory, has largely reduced the conversation Hitchens hoped to inform and enliven to the dueling screams of mobs. The perpetually outraged try not only to impose limits and proscriptions on what topics are suitable for debate and what positions are acceptable to articulate, but seek to enhance the ideological tribalism that makes intellectual independence nearly impossible.

Suffering under the noxious atmosphere of the tweet, slogan, and hashtag, Hitchens now looks like the last public intellectual, that rare thinker with the ability to address a variety of subjects and engage with a diversity of thoughts. The best public intellectuals are those who evade category. Hitchens was a pugnacious atheist, democratic socialist with libertarian sympathies, advocate of neoconservative foreign interventions, and committed foe of the religious right. He was also pro-life, a Bush supporter, and Obama voter who stunned the left with his defense of the Iraq war, and angered the right when he opposed waterboarding and NSA data mining.

No matter the topic or the position, Hitchens’ greatest consistency was his eloquence. A master of the essay and an exemplar of the beauty of the English language, his imagination, acting through the channels of his keyboard and pen, always managed to defy expectations in the demonstration of literary and journalistic excellence.

The legacy of Hitchens is currently under assault from men of lesser talents and inferior intellects. Many leftists have let loose with vomitous declarations that Hitchens was “Islamophobic,” due to his aggressive criticism of Islam, most especially its political application. Matthew Yglesias, in an exhibition of his own ignorance on the subject, recently posted to Twitter that he often imagines how annoying he would find Hitchens’ pro-Trump columns if the writer were still alive today.

Set aside Yglesias’s poor taste in implying that he is relieved Hitchens died of cancer: it is impossible to imagine Hitchens defending, much less supporting, the anti-intellectual con artistry of Donald Trump.

Another affront came from evangelical promoter Larry Taunton, who wrote a book based on two brief discussions with Hitchens in which he claimed against evidence and in direct contradiction to the testimony of his subject’s close friends that as Hitchens neared his death he was on the verge of a Christian conversion.

Perhaps the worst insult to Hitchens, though, came from Bill Maher, who despite his claims of friendship with the author, seems to have never read his actual work. While interviewing juvenile shock jock Milo Yiannopoulos, Maher called him the “young, gay Christopher Hitchens.” This was the same Yiannopoulos whose aborted and recently exposed manuscript for Simon & Schuster was festooned with editorial comments imploring him to inform himself on basic matters of history and politics, and stop making jokes about black men’s penises. It seems unlikely that a similar note ever appeared in the margins of Hitchens’ books on the Parthenon or George Orwell.

It is unfortunate, but not unpredictable, that many of today’s pundits and commentators would have difficulty appreciating Hitchens, because his work, method for intellectual growth, and refusal to conform to ideological label or expectation is almost alien in contemporary American discourse.

Cass Sunstein, in Republic.com and its sequel Republic.com 2.0, began documenting in 2001 what has now become as troubling as it is obvious. Despite having the Library of Congress at our fingertips, most Americans consume news and opinion for the main purpose of bias reinforcement. This has resulted in political coverage that plays a similar role to pornography, one of the most popular forms of entertainment on the Internet. It allows the reader to satisfy himself, constantly finding validation for his own ideas, never straying into the challenging or uncomfortable.

This polarity and tribalism is fertile ground for partisans who pose as public intellectuals, and in the process produce writing that is boring because it is formulaic. Ta-Nehisi Coates is possibly, at present, the most fashionable and recognizable essayist in America. But with the notable exception of his sociopathic confession that he felt no sadness or anger on September 11, 2001, has he ever written a sentence that his readers could not finish for him?

Writers now function as brands of regular programming, comparable to a classic rock radio station playing songs by The Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Bruce Springsteen. And just as the inclusion of George Jones or Jay-Z in the afternoon rotation would cause many loyal listeners to change the dial, so, too, is Coates unlikely to argue that America is a complex society, not entirely defined by its history and legacy of white supremacy.

Hitchens did not broadcast according to the standard format, and for that reason, beautifully failed to provide comfort to one partisan tribe. In his essay “Fetal Distraction” for Vanity Fair, he carefully examined conflicting perspectives on the moral, political, and legal dilemma of abortion, where he found justification for all but the most extreme positions, and confessed that he once accompanied a former lover for the termination of her pregnancy. He was equally punishing and forgiving to feminists who claim to protect “freedom of choice” as he was to those who claim to defend “the sanctity of life.”

He concluded that “The only moral losers in this argument are those who say that there is no conflict, and nothing to argue about. The irresoluble conflict of right with right was Hegel’s definition of tragedy, and tragedy is inseparable from human life, and no advance in science or medicine is ever going to enable us to evade that.”

The contemporary publication of a similar essay would likely elicit both accusations of misogyny and claims that the author supported murder.

Most tragic among many developments unfavorable for the maintenance of a lively intellectual culture has been the steady debasement of language. Hitchens’ greatest gift was his rhetorical talent. When essays and commentary are consumed solely for the purposes of ideological affirmation, eloquence is secondary to argument. Norman Mailer, a man of the left, once explained his annual donation to William F. Buckley’s National Review with the words, “Good writing wins the day.” It was good writing that enabled Hitchens to thrive as a public intellectual, in spite of the challenges and frustrations he presented to liberals and conservatives alike.

Political debate and cultural discourse are poorer for Hitchens’ absence. Considering that one of his rules for young writers was to “never be a spectator of unfairness or stupidity,” if he were still alive, he would have plenty to say about our current abysmal state of affairs. The mystery is whether or not anyone would still have the open mind and ear to hear it.

David Masciotra (www.davidmasciotra.com) is the author of Mellencamp: American Troubadour (University Press of Kentucky), Barack Obama: Invisible Man (Eyewear Publishing), and the forthcoming Half-Lights at Evening: Essays on Hope (Agate Publishing).

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com