Is it perfect timing or merely perverse to release a documentary promoting the design philosophy “Less, but better” during the holiday season? The opening moments of Gary Hustwit’s “Rams,” about Dieter Rams, is more likely to have you revising your gift list than tossing it out. As the camera pauses on the details of the eighty-six-year-old design legend’s single-story home, built in 1971 in Kronberg, Germany, you may find yourself wondering if you, too, need to buy a wall-mounted stereo (the Audio 2/3, designed by Rams for Braun, in 1962-1963) or a boxy leather swivel chair (the 620 armchair, designed by Rams for Vitsoe, in 1962), or to take up the art of bonsai, which Rams practices in his compact, Japanese-inspired garden.

After this montage, the sound of birds chirping is replaced by the sound of typing, and we see Rams seated in front of the rare object in his home that’s not of his own design: the red Valentine typewriter, designed by Ettore Sottsass and Perry King for Olivetti, in 1968. (Rams doesn’t own a computer.) If you listen to Rams—speaking his native German, with subtitles—rather than just look at the elements of his edited world, you will appreciate how his aesthetic and his ethic align. “Less, but better,” the title of his 1995 book, is, Rams says, “not a constraint, it is an advantage which allows us more space for our real life.”

It is a lesson that Rams’s many fans in the design world would be wise to heed. Rams is still living with products that he designed or purchased in the nineteen-sixties, whereas we are forced to upgrade our buttonless rectangles every few years. He is also responsible for the dominant technological aesthetic of our age: smoothness. And now is a particularly good time to contemplate his legacy: “Rams” will be released on Wednesday and the exhibition “Dieter Rams: Principled Design” is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through April, 2019.

The SK 4 phonograph and radio, designed by Dieter Rams for Braun, in 1956.

Photograph by Sebastian Stuch. Courtesy The Museum Angewandte Kunst / The Philadelphia Museum of Art

On the wall that welcomes visitors to the show, the exhibition designer Jamie Montgomery has blown up a circular grille from Rams’s RT 20 tabletop radio (1961) to state, as the “Principled Design” curator Colin Fanning put it, “Details matter.” Rams says in Hustwit’s movie that he will never retire; he’s still working with Vitsoe on potential new products and reissues. But, if he had to do it all over, he might think about design at a different scale. At a 2016 talk in Munich, shown at the start of the film, the designer Fritz Frenkler asked Rams what path he would choose if he were starting his career today, and Rams points to landscape architecture, because “shaping our environment is the most important thing . . . This starts with the landscape, not with the design of a machine.”

When an audience member at the panel asked him about Tesla, he said,“We don’t need anything faster.” (Rams drives a Porsche.) “We need to rethink the entire transportation system.” Not cars, but traffic.

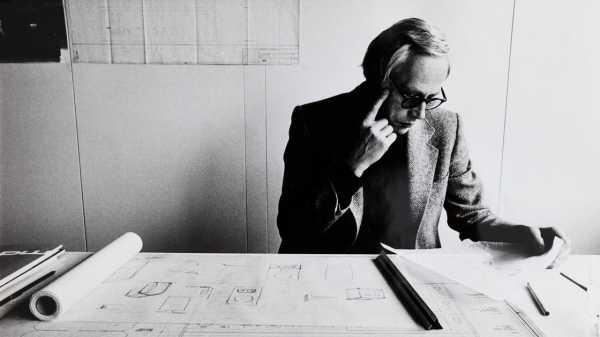

Rams was born in 1932. In 1955, after training as an architect, he went to work for Braun, the consumer-electronics company, which was then run by a pair of brothers, Erwin and Artur Braun. The brothers realized that they had a tremendous opportunity in the postwar world: to unite progressive design with new advances in engineering and materials. They partnered with the new Ulm School of Design and hired many of its graduates, seeking a functional look for the elements of contemporary life: stereo systems, radios, slide projectors—products that were often white as milk and crisp as pocket squares. Rams was the head of design at Braun from 1961 to 1995. Along the way, he was also instrumental in the success of the furniture company Vitsoe, which launched Rams’s 606 Universal Shelving System, in 1960, and never stopped producing it.

Hustwit’s Rams movie and Fanning’s Rams show evoke the aesthetic of the designer’s products. But fetishization isn’t the point that audiences should take away. “In reality the design is meant to disappear; it is meant to be the structure for everyday life,” Fanning says, echoing the fifth principle in Rams’s oft-invoked Ten Principles of Good Design: “Good design is unobtrusive.”

I would have loved to see some #shelfies in the film or the exhibit, demonstrating how much stuff, and of what marvelous variety, one might organize on a wall of Vitsoe 606 modules. How do they hold up? Why do people love them? Can they be assembled, as Rams hoped, without a manual? I wanted to see his products in the wild, his designs dealing with mess. Hustwit, in his director’s statement, says he wanted to make his film uncluttered, without endless encomiums from other designers, but the result feels visually hermetic, repressed, in a way that Rams himself is not, especially when discussing failures of design.

Vitsoe’s 606 Universal Shelving System was introduced in 1960.

Photograph Courtesy Vitsoe / The Philadelphia Museum of Art

The film’s peak comes when Rams is let loose in the Vitra Design Museum’s Schaudepot, a giant house-shaped structure that houses some twenty thousand objects. Rams, gesturing with his Nanna Ditzel-designed cane, takes us on a tour, rapping approvingly on a Hans Wegner chair, nodding at Charles and Ray Eames’s E.S.U. shelving, shrugging at the Marshmallow sofa of George Nelson & Associates. (Nelson was a friend, Rams says, but, “generally it is too playful for me.”) When told that Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge is the most expensive piece of design ever sold at auction (one sold for two million pounds, in 2015), he shakes his head sadly. “It leads to misunderstandings. Suddenly we hear, ‘Design just means expensive.’ ” Mateo Kries, the director of the Vitra Design Museum, seems delighted by Rams’s critical firecrackers. “He’s also from that generation where designers dared to say, ‘This, in my opinion, is bad design.’ Today you would more often hear, ‘This is interesting.’ ” When you are eighty-six, why mince words?

I remembered loving Hustwit’s first design documentary on another ubiquitous yet unseen monument of modernism, “Helvetica,” so I went back and re-watched it. Between visits to Helvetica-loving designers of multiple generations, Hustwit films Helvetica on posters, Helvetica in stores, Helvetica on planes, Helvetica in the New York City subway. Suddenly, the background music became the symphony.

The closest we get to user experience in “Rams” is an interview with Naoto Fukasawa, one of the three contemporary designers whom Rams admires. We see Fukasawa in his own monochrome home, touching, for the first time, the T3 pocket transistor radio designed by Rams for Braun, in 1958. The moment you see his fingers on the circular frequency dial set opposite a square speaker, you make the mental leap to the iPod that Jony Ive and the Apple industrial-design team produced, in 2001. The click wheel was here, in an earlier, chunkier pocket music device. Ive has always acknowledged his debt to Rams (he contributed a foreword to Sophie Lovell’s book “Dieter Rams: As Little Design as Possible”) but, as the Philadelphia exhibition text suggests, Ive, embedded within Apple’s upgrade cycle, may have missed the point: “the rapid obsolescence and environmental impact of these devices sits uneasily against Rams’s advocacy of long-lasting, durable design.”

The minute design twitches of each year’s Apple launch are a far cry from the revolutionary change that the click wheel ushered in. Newfangled ports, rose-gold backs, the elimination of the home button—these don’t change our relationships to our phones, except to annoy. Seeing Fukasawa’s hands on the T3, I am reminded again that Apple is no longer making small phones for those of us who are perfectly comfortable with our small hands. The technological future Rams imagined in 1958 was tactile and user-friendly. Dongles would horrify him.

I recently read John Carreyrou’s book, “Bad Blood,” about the exposure of the Theranos fraud, and realized that Rams’s influence, via Apple, had been passed on to a new generation as an aesthetic rather than as an ethic. Theranos’s Elizabeth Holmes hired designers from the Apple team, and insisted for years that her blood-testing system fit inside a tabletop monochrome box—as if a toaster and a laboratory could and should look the same.

Rams’s collaborator on the ET55 calculator (1980), Dietrich Lubs, who is interviewed in the film, says that the Braun designers “were trying to eliminate the need for user manuals.” The new-products division at Braun, founded in the mid-sixties, focussed on new categories of objects for personal grooming and the desktop, which required even more attention to shape, color, and tactility. In a world where the On button is endangered, there’s something wonderfully clear about Rams and Lubs’s calculator’s green On and red Off buttons, rounded to meet the fingertip. In a world where even home coffeemakers bristle with nozzles and switches, there’s something wonderfully soothing about the Braun kitchen appliances, most of which have a single toggle switch. A few years back, frustrated by the chaos of my countertop, I ordered a vintage KF 20 coffee machine (designed by Florian Seiffert, in 1972) from eBay, and put it to work. It had a smaller footprint and simpler lines than any electric machine on the market today.

The KF 20 coffee machine, designed by Dieter Rams and Florian Seiffert, in 1972.

Photograph by Sebastian Stuch. Courtesy The Museum Angewandte Kunst / The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Mark Adams, the managing director of Vitsoe, collects such stories from customers (and uses a KF 20 himself). At the Philadelphia museum opening, he told me that he’s had customers put their 606s in their wills—“Make sure you get the shelves after I’m gone”—and has been asked by lawyers to value units in divorce proceedings. “Though of course,” he is quick to mention, as a modular system “it can easily be split.” It is this kind of story I wish there were more of in “Rams”—moments when inanimate objects inspire passionate emotion and artifacts of the recent past become heirlooms. Here’s a happier Rams story, also courtesy Adams: two lonely souls went looking for love after broken marriages. When they eventually went home together, they found they both had off-white 606s on their walls. Their subsequent cohabitation was written in the shelves.

Sourse: newyorker.com