“A photograph is a secret about a secret,” Diane Arbus said. In the case of Vivian Maier, the photographer was a secret, too. From the nineteen-fifties until a few years before she died, in 2009, destitute at the age of eighty-three, Maier took at least a hundred and fifty thousand pictures, mostly in Chicago, and showed them to nobody. It’s telling, perhaps, that one of her favorite motifs was to shoot her own shadow. For decades, she supported herself as a nanny in the wealthy enclaves of the city. But her real work was roaming the streets with her camera (often with her young charges in tow), capturing images of sublime spontaneity, wit, and compositional savvy. When pressed about her occupation by a man she once knew, Maier didn’t describe herself as a nanny. She said, “I am sort of a spy.” All the best street photographers are.

Maier’s covert work might have languished in obscurity if not for the chance acquisition, in 2007, of a cache of negatives, prints, contact sheets, and unprocessed rolls of film, all seized from a storage locker because she fell behind on the rent. When John Maloof, a Chicago real-estate agent, bought the material, everything about Maier’s identity was a mystery except for her name. It was only when he ran across her death notice, two years later, that her story began to unfold. (His wonderful documentary on the subject, “Finding Vivian Maier,” was nominated for an Academy Award in 2015.) Maier shot in both color and black-and-white; perhaps to establish her credibility as a “serious” artist, the first of her pictures to be widely disseminated were the latter. Now that Maier has earned her place alongside Arbus, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Lisette Model, Garry Winogrand, and other giants of the American street, a new book, “Vivian Maier: The Color Work,” and a related exhibition at Howard Greenberg Gallery (opening on November 14th) consider her eye for the vivid.

Chicago, 1978.

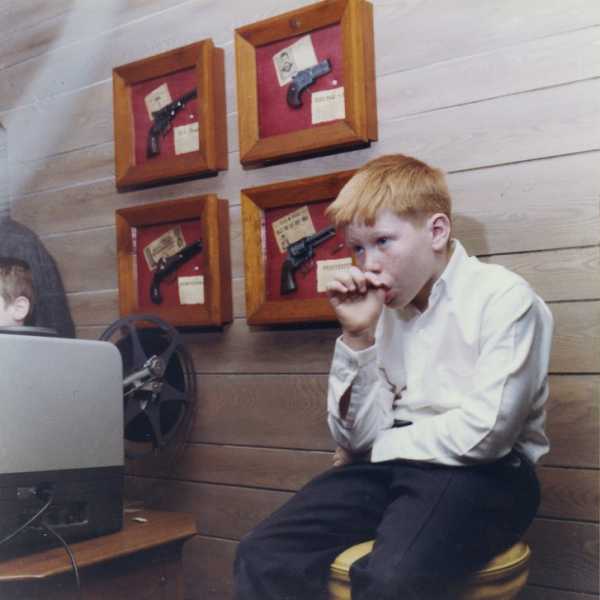

Maier is such an original artist that it feels a like a cheat to play games of compare and contrast. But, leafing through the book, it’s remarkable how often other photographers spring to mind. On an unknown date, at the Art Institute of Chicago, she pulled a Thomas Struth when she documented a mother (a nanny?) and a child staring raptly at a painting on the wall, both dressed in navy and white; the composition is centrally anchored by another child staring, defiantly, directly at Maier. In another image, a red-headed boy, who sucks his thumb while slumped against a wood-panelled wall on which four framed handguns are hanging, could be the shy, sullen cousin of Arbus’s manic boy with a toy hand grenade. The detached bumper and crash-crumpled metal of a Volkswagen Beetle, shot in Chicagoland in 1977, assumes sculptural proportions that invite thoughts of Arnold Odermatt, the Swiss policeman whose forensic photos of automobile accidents deserve to be more widely known.

Location unknown, 1960.

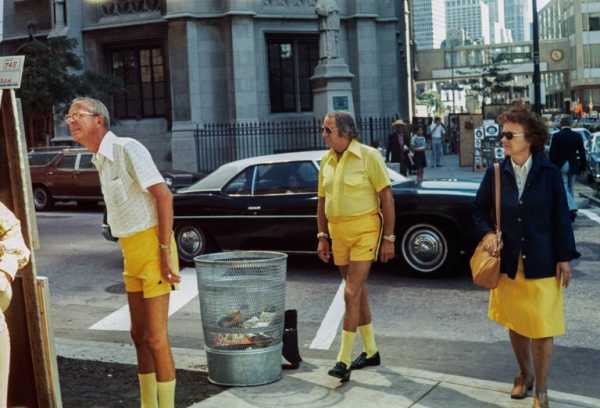

The Beetle was yellow, a color that brings out Maier’s best. In 1975, she took one of her shadow self-portraits against a green lawn dotted with little gold blossoms; cropped by the lens, the dainty, painterly landscape splits the difference between a Warhol silkscreen of flowers and the allover compositions of AbEx. (Note that Maier was shooting her shadow in the nineteen-fifties, roughly a decade before Friedlander, who is renowned for the gesture, did the same.) The same year, she came across two men on a sidewalk—one standing, one striding—both wearing canary shorts and lemon-fizz socks. To their right is a woman in a sensibly dark woolly cardigan and a daffodil-colored skirt. Their outfits are almost absurdly sunny, but not one of them is smiling.

Chicagoland, April, 1977.

Maier can pack an entire short story’s worth of details into a single frame. Consider the overly tan, skin-baring couple shot in an unknown location in 1960. They stand peeping through two cruciform holes in a high wall separating them from a swimming pool. The woman’s dingy white curls echo the hue of the stucco; his peeling, freckled back repeats its mottled texture. The ruched fabric of her bitter-orange bathing suit is the same palette and pattern as a poolside cushion in the near distance. Past the man’s ear, there’s a lively brunette whose blue one-piece is a shade darker than the water below. She’s thrown her arms in the air, as if describing a wild night at a party. The elderly pair are on the outside looking in, and it’s worse than having their noses pressed against glass—they can smell the chlorine. When you see that she’s clutching a wrinkly brown paper bag, the mise en scène becomes somehow sadder.

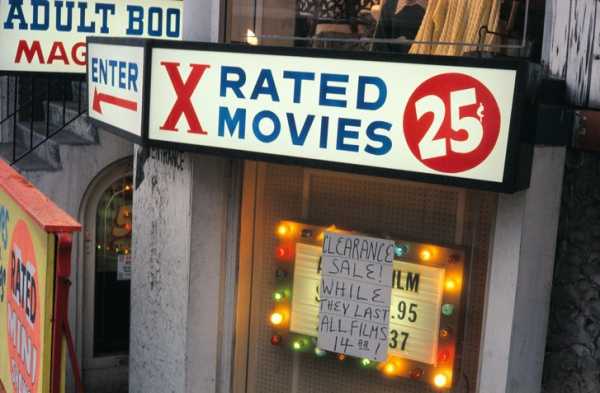

Location unknown, c. 1960–1976.

The Art Institute of Chicago, date unknown.

One question that has dogged the discovery of Maier’s photography is how a lowly nanny could make such high art. Let’s call that sexism. I’ve never heard anyone ask how another exceptional Chicago outsider, the visionary writer and artist Henry Darger, could have produced his fifteen-thousand-page magnum opus while holding down a job as a janitor. The photographer Joel Meyerowitz contributed a foreword to the new book, a canny choice given that, like Maier, he learned how to shoot on the streets. He also co-wrote (with Colin Westerbeck, who also contributes an essay) an esteemed volume on the genre, “Bystander: A History of Street Photography.” He concludes, rightly, that “Maier was an early poet of color photography.” But he also floats a wince-inducing theory about her knack for snatching secrets, what he terms all great street photographers’ “cloak of invisibility”: “She’s as plain as an old-fashioned schoolmarm. She’s the wallflower, the spinster aunt, the ungainly tourist in the big city . . . except . . . she isn’t!” Has Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” ever been defined in terms of his looks?

Location and date unknown.

Location and date unknown.

Chicagoland, March 1977.

Chicago, December 1974.

Chicago, 1975.

Location unknown, 1976.

Chicago, 1973.

Self-portrait, Chicagoland, 1975.

Self-portrait, Chicagoland, October 1975.

Sourse: newyorker.com