Each week, Richard Brody picks a classic film, a modern film, an independent film, a foreign film, and a documentary for online viewing.

“Columbus”

Photograph by Elisa Christian / Superlative Films / Everett

The video artist Kogonada’s first feature, “Columbus,” from 2017, is an extraordinarily well observed, written, and performed movie about artistic passion and the burdens of family life—of grown children’s relationships with their parents. The title refers to Columbus, Indiana, a real-life center of modern architecture, where a young woman named Casey (Haley Lu Richardson), an inspired aesthete who is a sort of architecture nerd, is whiling away her time working at a local library because she’s staying home to care for her mother (Michelle Forbes), a recovering addict. Meanwhile, a Korean architect visiting the city is taken suddenly ill and hospitalized, and his son, Jin (John Cho), comes to Columbus to take care of him, too. There, Casey and Jin cross paths and begin a friendship that puts Casey’s future—and her relationship with her mother—into question, while Jin confronts the looming shadow of his own father’s great accomplishments. Kogonada writes brilliant dialogue—terse, wry, probing—for young intellectuals, and Richardson and Cho don’t so much deliver their lines as seem to discover them, as if from their own thoughts. As for the architecture, Kogonada films it—and his characters’ place alongside it—with a probing, admiring ardor.

Stream “Columbus” on YouTube, Google Play, and Amazon.

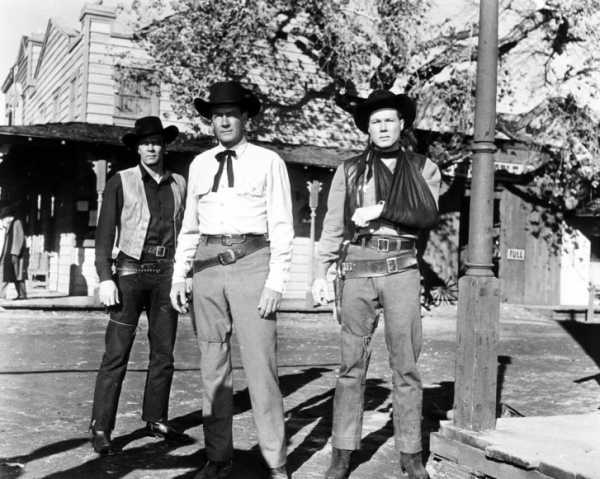

“Wichita”

Photograph from Everett

Jacques Tourneur, born in France, long a resident of Hollywood, and hardly heralded in his lifetime, made a batch of genre films that, under the guise of ordinary program-fillers, were among the most boldly confrontational political movies coming from the studios at the time. One of them, “Wichita,” from 1955, is a gun-control Western with modern resonances, in which the question of unregulated arms ownership is connected to the effort and ability of parents to protect their children from indiscriminate violence. Tourneur reworks the genre’s mythic framework with a story that’s set in 1874 and is centered on a fabled lawman, Wyatt Earp (played by Joel McCrea, who also starred in Tourneur’s similarly defiant Western “Stars in My Crown”), whose principled and humane efforts come into conflict with the town’s business interests. Plus ça change.

Stream “Wichita” on YouTube, Google Play, and other services.

“Imperial Dreams”

Photograph from Everett

Malik Vitthal’s 2014 drama, “Imperial Dreams,” is a horror story of mass incarceration and the accompanying mechanisms of social control inflicted on the poor and the nonwhite. It’s also a tender, intimate, love- and pain-filled multigenerational family story that’s built upon the damage wrought by that system. John Boyega stars as Bambi, a young man who returns to Watts after serving a prison sentence for assault with a deadly weapon. Bambi, a published writer, comes back to a house in the projects where his Uncle Shrimp (Glenn Plummer), a drug dealer, has been caring for Bambi’s young son, Daytone, while the child’s mother is also in prison. Bambi’s mother, a crack addict, lives there, too. Bambi is planning to get his writing career going, and to get Daytone out of the projects, but he is being pressured to work for Uncle Shrimp. Vitthal captures, with a taut dramatic precision, the cruel absurdity of a bureaucracy that condemns its clients’ very existence to a virtual administrative criminality, as encapsulated in a sequence where Bambi, seeking employment, can’t get a job without a driver’s license, can’t get a license without paying the fifteen thousand dollars in child support that (through government filings) he owes, and can’t pay child support without a job. Meanwhile, child services is threatening to take custody of Daytone because of Bambi’s unstable housing situation. “Imperial Dreams” blends the analytical thoroughness of a documentary with a symbolic and furious dramatic compression; it was unjustly overlooked at the time of its brief release.

Stream “Imperial Dreams” on Netflix.

“Boy”

Photograph from Everett

The warped ideals and traumatic violence of Japan’s involvement in the Second World War and the economic transformations of postwar society bear monstrous results in Nagisa Oshima’s 1969 drama “Boy.” It’s the story of a child named Toshio, who is thrust by his brutal father (a wounded war veteran) and indifferent stepmother into a life of crime. He feigns injuries to collect compensation, a scam that the family plies in their wanderings and narrow escapes throughout Japan. (The drama is based on a true story.) Oshima’s vision of societal rot and family cruelty is rooted in a lofty cinematic irony; his widescreen images of cities, small towns, and rural landscapes have a soft-brushed, splashily colorful allure that contrasts appallingly with the film’s intimate degradations. Meanwhile, Toshio’s sweetly complicitous bond with his little brother Peewee nods toward a pair of classic movies by Yasujiro Ozu, “I Was Born, But . . . ” and “Good Morning.” As in Ozu’s films, Oshima offers a severely critical view of traditional culture and technological innovation alike, but, unlike Ozu’s world, Oshima’s film acknowledges no substrate of warmth, tenderness, or family feeling; the family merely reproduces, in miniature, society’s relentless battles for money, power, and advantage.

Stream “Boy” on FilmStruck.

“No Home Movie”

Photograph by Icarus Films / Everett

Perhaps no filmmaker has filmed her own family stories as insistently or as directly as Chantal Akerman. Her final film, “No Home Movie,” from 2015, documents her relationship with her mother, who had been a central presence in her fictional films as well as in nonfictions from early in her precocious career. Akerman was born in Brussels, where her mother—a Jewish woman from Poland who survived internment in Auschwitz—still lived. But Akerman’s movie career was made largely in Paris, and her work took her on worldwide travels. “No Home Movie” is a sort of unwilling travelogue that documents and probes her distance from her childhood home when her mother was ailing. (Many of the film’s most striking scenes take place via Skype.) The filmmaker’s return to Brussels culminates in a series of conversations with her mother, in person, that delve deep into family history, into their relationship to their Jewish heritage, and into the personal legacy of the Holocaust. It’s also, literally, a movie about having a home and having no home—about varieties of exile and loss, about the elements of identity and their fragility. The intensity of its love is matched by an inconsolable pain that Akerman nonetheless gives a personal and original aesthetic form.

Stream “No Home Movie” on Amazon, YouTube, and other services.

Sourse: newyorker.com