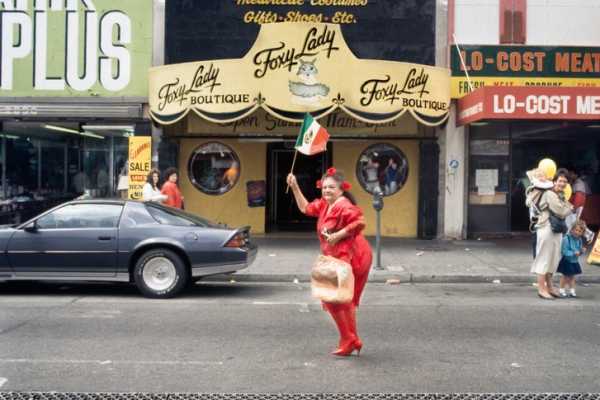

The photographer Janet Delaney first came to San Francisco in 1967, for the Summer of Love. By the time she began living in the Mission, in the nineteen-eighties, she had learned Spanish and trained herself to recognize moments of quiet revelation in the streets. “I’ve always seen San Francisco as a small place where big things happen,” she says. “There’s a kind of freedom in being on the West Coast, as if your parents aren’t around.” She was an interloper in the Mission, not having been raised there. And yet, like many new arrivals, she found her place—and her subject—by studying the people for whom it was home.

The area was busy and fast-moving then, with domestic culture spilling out onto the public turf. Photographing life in the streets was fluid and spontaneous work—“like shooting from the solar plexus,” Delaney says—and often it was unclear what she had until she got back to her darkroom. In this way, she was capturing, not composing; gathering, not trying to bear out a story. In time, though, a story did form in her photographs, much as a drift grows from accumulated flakes of snow. The story was about the inflow of culture that kept a pluralistic district alive—and the way that this flow drove life into the local streets, and then beyond them, toward a bigger world.

“Three Contestants,” 1988.

In “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” published in 1961, the urban theorist Jane Jacobs famously suggested that diverse and densely populated neighborhoods helped a city thrive. “They are physical, social and economic continuities—small scale, to be sure, but small scale in the sense that the lengths of fibers making up a rope are small scale.” What Jacobs may not have foreseen entirely was change in the structure of America’s urban labor force.

“Drummers, Golden Gate Bridge 50th Anniversary,” 1987.

“I May Not Get There . . . First Martin Luther King Jr. Day Parade,” 1986.

The Mission’s geography ultimately put it in the path of larger concerns. “It’s a key location in the city, near downtown, and you had a lot of factories,” Erick Arguello, an activist who grew up in the Mission, says. The deindustrialization of the postwar years became flagrant on the street as the eighties progressed. Factories closed. Automated tools, such as bank A.T.M.s, began replacing local workers. Meanwhile, the world rushed in. BART, the Bay Area’s commuter train, had opened two stations in the Mission in the seventies, bringing the neighborhood daily commuter traffic. Refugees from wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua subsequently arrived, driving up the population during a short period. From 1980 to 1990, the Mission gained five thousand residents, the only growing ethnic demographic being Latinos.

“Woman with Purse,” 1985.

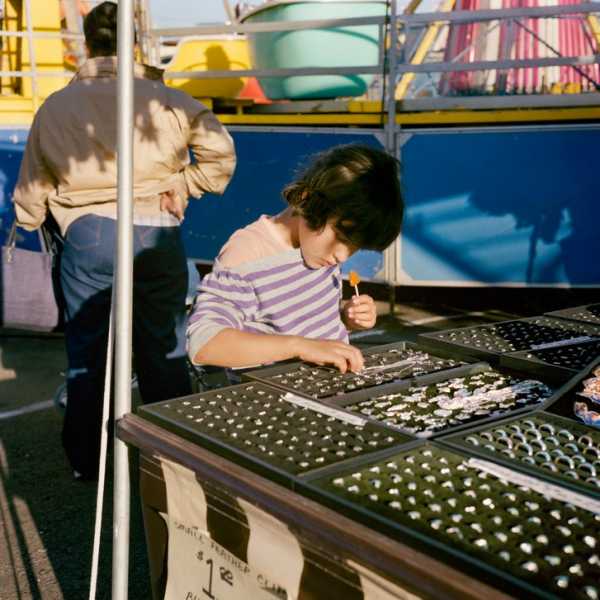

“Girl Looking at Jewelry,” 1984.

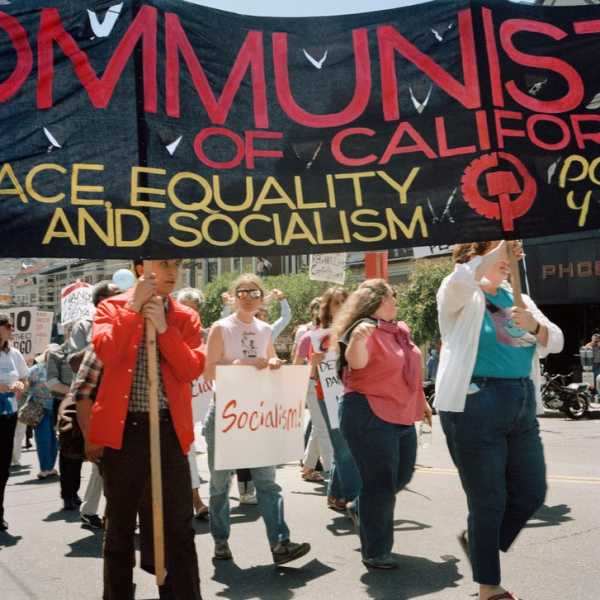

New pressures played out on the streets. “There were a lot of things happening politically,” Lou Dematteis, a photojournalist who also worked extensively in the Mission, says. “One of them was certainly the demonstrations against the war in El Salvador that the Reagan Administration was prosecuting.” Solidarity with the Sandinistas in Nicaragua became a common cause, too. Activism—“demonstrations and marches,” Dematteis says—gave street culture fresh intensity, opening a new chapter in the neighborhood’s public life. Dematteis was among those to help establish the San Francisco Carnaval. Popular and culturally absorbent, the festival became a calling card of the more trafficked, more conspicuously vibrant Mission—a neighborhood that got visitors from elsewhere across town.

“Anxious Crowd,” 1986.

Most of these changes reached Delaney’s lens. She photographed Carnaval, and attended the city’s first Martin Luther King, Jr., Day parade. “You had this group of gay men advocating AIDS awareness, and another group lobbying for Native American rights,” she recalls. She noticed that the Heart of the City farmers’ market, at the Mission’s northern apex, had become a pluralistic public meeting ground. “It was the epitome of immigration, for me,” Delaney says. “All of these families from Russia, Southeast Asia, and Central America, who were living all over San Francisco, came together.” Nearly everybody in the Mission, it seemed, knew someone who’d been killed in Central America or who had arrived as a refugee. (To some degree, the flow went both ways: aspiring Sandinistas had trained in nearby Bernal Heights.) Like many people in the Mission during those years, Delaney became ensnared in the district’s causes. During the summers of 1984 and 1985, she went to live and work in Nicaragua—Dematteis left to do the same—pulled into a broader path of interest by the currents of a local neighborhood meeting a broader world.

“Crowd Waiting,” 1986.

Meanwhile, at home, creative people like Delaney worked to celebrate the vibrant mix of the place. As a photographer, she had educated herself deeply enough in Mission life to be able to recognize moments of true interest: she understood the bones and sinews of the neighborhood, the local power structures and the hidden tensions. She was not a tourist for whom everything was colorful and new. But, as a relative outsider whose presence was itself changing the landscape, she also became conscious of the weight of her attention. Her photographs, showing a point of view both inside and outside, are extraordinary pieces in part because they were made from the vantage of the Mission’s porous boundary. They are a window, through time, on the gate through which the district’s change slowly arrived.

“Girl with Dollar,” 1985.

“‘Cookies not Contras’, Peace, Jobs and Justice Parade,” 1986.

Today they trace a transformation that Jane Jacobs marked in cautionary tones. “Because of the location’s success, which is invariably based on flourishing and magnetic diversity, ardent competition for space in this locality develops,” she wrote. “Whichever one or few uses have emerged as the most profitable in the locality will be repeated and repeated, crowding out and overwhelming less profitable forms of use. . . . Those who get in or stay in will be self-sorted by the expense.” A vibrant public culture commands an audience, in other words, and an audience creates a market. A number of Delaney’s photographs are of people studying their surroundings—“watching and waiting for something to happen,” as she puts it—and, with the eyes of the present, those images tell a poignant story. In the Mission, in the eighties, to watch the street was to be implicated in its change.

“Boy with Transformer, First Martin Luther King Jr. Day Parade,” 1986.

“Socialism!,” 1986.

The unweaving of local networks in America is well-documented. In “Bowling Alone,” published in 2000, the political scientist Robert D. Putnam traced a decline in what he called “social capital”: the bonds that hold local communities together and enable coördinated action. In the Mission, though, soaring prices and transient neighbors have fed a sharper spiral of exclusion. “I don’t have one African-American friend that I grew up with left in the Mission,” Roberto Y. Hernandez, a lifelong resident and community leader, notes. “They’ve all been evicted. My Filipino friends? All gone. So are a lot of Latinos.” Instead, the Mission today is dense with farm-to-table restaurants, furniture shops, and cafés where baristas pour designs into the foam of lattes made from fair-trade beans. City residents usually welcome such change piece by piece—most people are pleased to have a place to get good coffee in their neighborhoods. But the new offerings, increasingly, break old networks apart. “I don’t feel welcome anymore in the neighborhood where I was raised,” Arguello says. For most San Franciscans now, even those who are well-off and new to town, the Mission has become a place to visit, not a neighborhood in which to settle down and live.

“Dexter King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s Son, at First Martin Luther King Jr. Day Parade,” January 26 ,1986.

“American Flag and Holy Bible,” 1986.

In that sense, Delaney’s Mission photographs (collected in a new book, “Public Matters”) capture the last moment when American neighborhoods were the essential nodes of a true public culture—a tight network of pluralistic local life that spilled into the streets. At the same time, the photographs record the slow, often enthralling transition away from that style of urban living and toward the geographically scattered, spectacle-oriented, socially channelled experience of cities today. People come together less in markets now than they do in Delaney’s photographs. (For one thing, they do more buying online.)

“Virgin Mary in the Ice,” 1984.

To blame the transformation of the Mission only on recent incursions and digital life, though, is also to miss the story that these photographs tell. What Delaney captures so intimately is the beginning of a process of opening up, of crowding in, of making the streets more than just a place where local residents crossed paths on the way to markets or to work. The public engagement that they bring to life was both the high point of an old era and the starting point of a new one. For decades, San Francisco has prided itself on its openness—it has wanted its people to bring in pollen from a broader world, and then converge. The twenty-first-century Mission is not an exception to the nineteen-eighties neighborhood that Delaney photographed but the longer story of its efflorescent growth.

“Mother and Daughters Behind Barricade,” 1986.

For longtime residents, the project these days is to keep the Mission open without losing all of the old bonds. Hernandez was born in the neighborhood, and spent most of his youth here. He bought his current house two decades ago. He calls himself “the captain of the block,” and takes the title seriously. But now he regards himself more as a keeper of the memory of place. When new people move in, he greets them. “I say ‘good morning,’ and they usually look at me like I want something,” he says with a laugh. “But I go up, and I say, ‘Hi. You know what? I’m Roberto. I live here.’ ”

“Foxy Lady,” 1983.

Sourse: newyorker.com