Ethan Hawke is quite right about the excess of critical enthusiasm for superhero movies, but he’s misguided in criticizing fantasy and prioritizing realism.

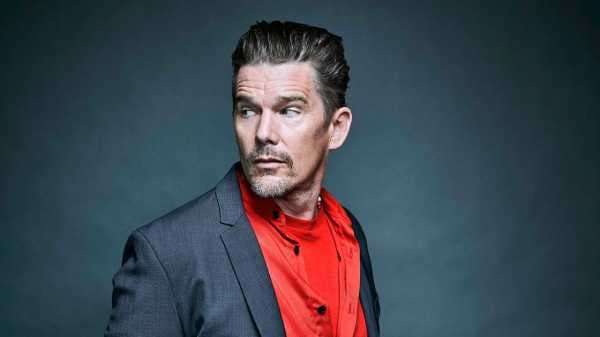

Photograph by Brad Trent / The Sunday Times / Redux

At the end of a recent interview with The Film Stage, Ethan Hawke delivered a remark about superhero films, crowning his lament that some of the best movies of the time are virtually ignored in the movie marketplace:

Now we have the problem that they tell us Logan is a great movie. Well, it’s a great superhero movie. It still involves people in tights with metal coming out of their hands. It’s not Bresson. It’s not Bergman. But they talk about it like it is. I went to see Logan cause everyone was like, “This is a great movie” and I was like, “Really? No, this is a fine superhero movie.” There’s a difference but big business doesn’t think there’s a difference. Big business wants you to think that this is a great film because they wanna make money off of it.

In the echo chamber of Film Twitter (the cinephilic circle that chats on the site) and other virtual coffee rooms and water coolers, this comment has received as much short-term attention as any of Hawke’s performances. In challenging the beast of popularity, the actor awakened a latent range of furies and sympathies.

Hawke’s career has largely been made in earnest live-action dramas. Just this year, he delivered a ferocious and agonized performance in Paul Schrader’s “First Reformed,” which is precisely inspired by, and has been aptly likened to, films by Robert Bresson and Ingmar Bergman. The first word of interest in his riff is “they,” which he goes on to define as “everyone.” But who is really responsible for praising a film like “Logan”? It isn’t “big business,” as Hawke implies—the studios say that every movie they make is great, in advertising and promotions. The people who “talk about it,” rather, are critics, whose reviews of “Logan” score ninety-three per cent on Rotten Tomatoes (and a more nuanced seventy-seven on Metacritic). Some praise the movie fervently with comparisons to classic Westerns.

Hawke puts his finger on an authentic phenomenon, albeit not exactly a new one: the tendency of critics to review popular movies deferentially. This is part of a peculiar feedback loop between critics and “big business”: critics respond in advance to the hype surrounding movies that, through marketing, have become big things even before their releases, thus fuelling the movies’ actual popularity (measured in ticket sales) when they are released. This unhealthy symbiosis is, in part, a result of critics’ fear of isolation from readership. At a time when journalism is under economic siege and the jobs of critics are increasingly imperilled, critics legitimately fear alienation from the mainstream. In the case of superhero movies, however, the mainstream of fans is itself a peculiar niche market; it isn’t merely people who go to the movies but social-media users who express fandom as fanaticism, treating critics who dislike a superhero movie as infidels who have questioned a tenet of their faith and a strut of their identity. (The multilayered fantasy of Jared Hess’s “Gentlemen Broncos” offers a vision of the uses and abuses of superheroes, the personal and psychological needs that they fulfill, and the quasi-religious devotion that they inspire.)

There’s also a sincere critical orientation (as expressly formulated by Pauline Kael) toward the concept of movies as a popular art form; from there, it’s a short step to treating a movie’s ability to connect with a large audience as a mark of merit in itself. This is compounded by the critical enthusiasm for craft, for professionalism, for technique skillfully employed and a story (such as it is) efficiently told, as in the recent acclaim for the latest “Mission: Impossible” installment. And there is a political aspect to this critical taste: objects of mass culture are rightly recognized to reflect prevalent social values, ideals, and prejudices, and therefore to require close critical analysis. But the mere fact of spending large amounts of time pondering these works leads to a critical Stockholm syndrome, a belief that the movies in question are of sufficient quality to merit the sustained attention.

So Hawke is quite right about the excess of critical enthusiasm for superhero movies; he’s right to note the missing asterisk. And he’s right that the problem is “big business,” which is to say the administrative structure, the superhero-industrial complex, the web of corporate decision-making in which these sorts of movies are enmeshed—and by which their directors are constrained. The producers make sure that the movies are director-proof—that the product will remain product, will remain sufficiently conventional, impersonal, merely (if sometimes impressively) professional. The same problem afflicts many, even most, of the classic-studio-era Hollywood movies—the great ones were, and remain, the exceptions. But it’s a special problem with superhero movies because they’re, for the most part, very expensive and very complicated to make. The kind of artistry that it takes to make a comprehensively good one is unusually wide-ranging—it encompasses screenwriting, the direction of actors, a mastery of the mythology, and the use of C.G.I. (in effect, animation). But, above all, it requires the same kind of creative freedom that any good movie requires, and that rarely comes with big-budget, big-studio productions. (Even “Black Panther,” which is perhaps the apogee of artistry in the genre, is locked into conventional and familiar action scenes.)

Where Hawke’s criticism of superhero movies is misguided, and damaging, is in his dismissal of the idea that a movie about “people in tights with metal coming out of their hands” can rival the films of Bresson or Bergman in artistry. He’s criticizing fantasy and prioritizing realism, which isn’t the same thing as reality. Superhero movies are merely a subset of cinematic fantasy; the tights and metal hands in “Logan” aren’t different from the costumes of the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion, or from the vampire in “Nosferatu,” the monster in “Frankenstein,” the robot in “Metropolis,” or the fantastic elements of any number of great works from classic or modern cinema. Some of the best movies of all are fantasies, ever and now. (Four of my top-ten films from 2017—“Get Out,” “Slack Bay,” “A Ghost Story,” and “Sylvio”—are fantasies.)

The ease of realism, the psychological illusion that reality is given to the filmmaker by the mere fact of pointing the lens and shooting, has led to the critical delusion that a movie filmed realistically actually gets at more of reality than one that involves the imagination and the creation of fantasies. The result is an ongoing, endemic indifference to inner lives (whether those of characters or of filmmakers), a repudiation of characterization and context that leaves much of the current “realist” cinema—whether studio-made or independently produced—more deadening than some mediocre superhero movies. Realism is overrated, not only by Hawke but by critics who fear that they are devoting their lives to frivolity as much as they fear charges of élitism and snobbery. In pointing out the absurd critical enthusiasms for some uninspired and bloated fantasy movies, Hawke has diagnosed an authentic phenomenon, but his proposed cure may be worse than the disease.

Sourse: newyorker.com