Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Last year, for my birthday, my wife gave me a copy of I Remember, a unique memoir by artist Joe Brainard. It’s a neat little book, less than two hundred pages long, composed entirely of short, often one-sentence paragraphs beginning with the words “I remember.” Read a few of them and you’ll get the gist:

I remember light green notebook paper. (Better for the eyes than white.)

I remember that the minister’s son was wild.

I remember chewing gum. Blowing big bubbles. And trying to get gum out of my hair.

I remember Dole pineapple rings on a salad with cottage cheese on top, and sometimes with a cherry on top.

I remember the Liz-Eddie-Debbie scandal.

I remember “Blue Suede Shoes.” And I remember having a pair.

I remember trying to figure out what it was all about. (Life.)

The memoirs are not organized in any logical order, nor do they form a story in the conventional sense. Yet they do create an image of one man’s American childhood and adolescence in the 1940s and 1950s, evoking the experience of growing up in general. I Remember does not focus on the sequential episodes that adults might find interesting in retrospect. It organizes random impressions (“I remember it rained on one side of our fence and not on the other”), oddities and visual details (“I remember really thin belts”), and fragments of social and technological reality, presented in the simple form that a child would perceive (“I remember DDT”). Memoirs do not go down rabbit holes; they wander through memory. They are also honest and unforgiving. (“I remember feeling sorry for the kids at church and school who had ugly mothers”). I Remember is an easy book to read, but it was probably not easy to write.

What we read

Discover great new fiction, nonfiction, and poetry.

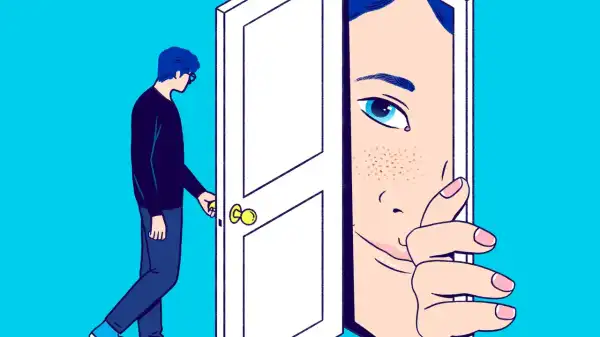

The book feels especially magical because it so clearly describes everyday moments. Our memories are treasure troves that we struggle to open; self-consciousness, forgetfulness, and critical thinking block the way. Brainard seemed to move through them effortlessly. In the afterword to I Remember, his poet friend Ron Padgett recalls how their circle responded to the book: “Everyone saw that he had made a remarkable discovery, and many of us wondered why we hadn’t thought of this obvious idea ourselves.” Writing memoir can be dull, daunting, self-indulgent; why not just remember?

Ever since I read “I Remember,” I’ve followed Brainard’s approach to my computer file. He drew inspiration from the terse, to-the-point phrases of Gertrude Stein and the repetitive images of Andy Warhol. (Fortunately, my colleague David S. Wallace recently published an appreciation of Brainard’s work as a poet, artist, and cartoonist.) My ambition is simpler: I’ve settled for memories of the blue-and-brown sandals my mother bought me in kindergarten that I found unattractive; of Kathy, the girl in seventh grade I was thought to have a crush on because we hung out too much; and of being so terrified by a terrifying scene in a science-fiction movie that my father had to escort me out of the theater. I’m no Joe Brainard—my memories would bore you, so I won’t go on listing them. But they don’t bore me.

Like many, I believe that memory leads to recollection. We can remember a lot if we give ourselves the time and space to do so. Most of the time, we simply glide briefly down memory lane. It’s like taking a walk just a few blocks from your home; since you start at the same point each time, you see the same places over and over again. We may return to scenes that are most relevant or reminiscent of our current lives. But if you walk a little further, you may discover useful memories that have no obvious importance. Does it matter that your first watch was a Casio F-91W — a square, rubber digital watch with tiny metal buttons? That you used to be afraid of the waves at the beach? That the paint in your elementary school hallway smelled sweet?

Sourse: newyorker.com