Bernd and Hilla Becher, a husband-and-wife team who spent five decades making rigorous and reverential pictures of industrial architecture, were among the most influential photographers of the second half of the twentieth century. Their work (which is the subject of a major retrospective just concluded at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and soon moving to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) broke through the previously rigid firewall between the worlds of photography and contemporary art. It was championed by minimalist and conceptual artists such as Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt, and showcased in major international art exhibitions, including Documenta and the Venice Biennale. As teachers, the couple birthed an entire movement—dubbed the Becher School—which produced some of the most celebrated photographers of the late nineties and early two-thousands. (Bernd was actually the only member of the duo who held a teaching position, at the fabled Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, but students frequently met at the couple’s home.) To some, however, their work was deadly dull. In 1977, the critic Hilton Kramer wrote in the Times that the Bechers’ photographs “look like the sort of pictures one sees in a real estate office.” The unflappable Hilla was said to have responded, “That’s O.K. We like real-estate photographs.”

“Coal Bunker, Zeche Concordia, Oberhausen, Ruhr Region, Germany,” 1968.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung

The Bechers met as colleagues at the Troost Advertising Agency, in Düsseldorf, in the late nineteen-fifties, and they overlapped soon afterward as students at the Kunstakademie. They quickly discovered that they had complementary interests. Bernd was working on drawings and photo collages of factories, attempting to capture his fondness for their Byzantine complexity and hulking scale, but he lacked extensive training as a photographer. Hilla, meanwhile, had decided to become a photographer as a teen-ager and had worked professionally for years, cultivating an interest in the novel forms of machine parts and the beauty of natural specimens, which she photographed against stark black backgrounds. Fascinating examples of both artists’ early work are on view in the current exhibition, much of it never before shown. Hilla’s eye for the taxonomic was influenced by her love of the natural sciences, and in particular by the drawings of the German naturalist Ernst Haeckel. Bernd was a fan of the flinty, dispassionate work of artists associated with the interwar New Objectivity movement, especially that of August Sander, whose impossibly ambitious project “People of the Twentieth Century” sought to create a compendious photographic document of the German people, organized according to broad types.

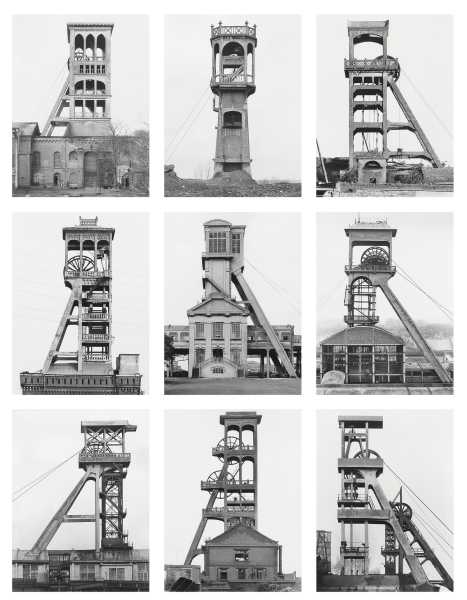

“Winding Towers,” 1967-88.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

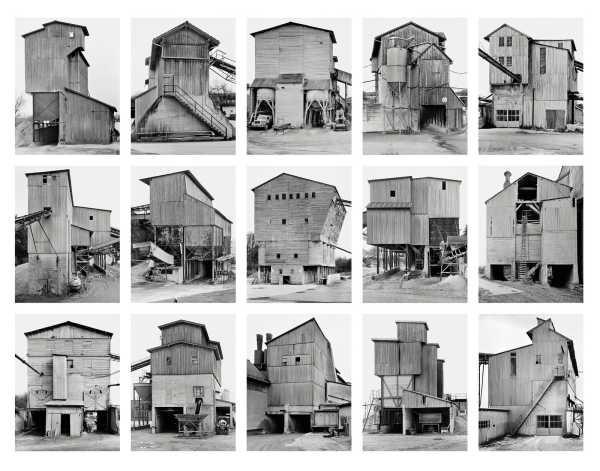

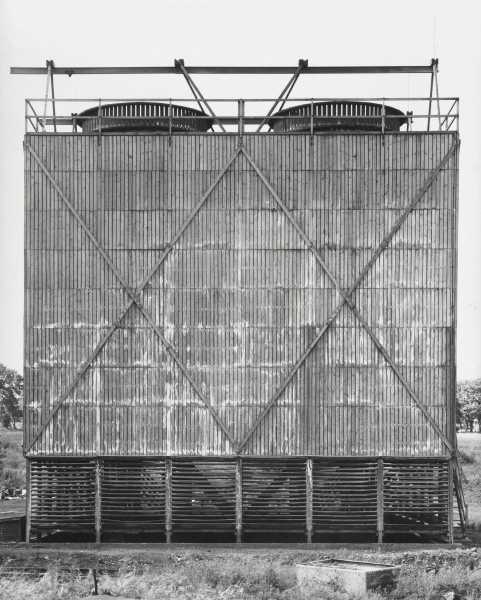

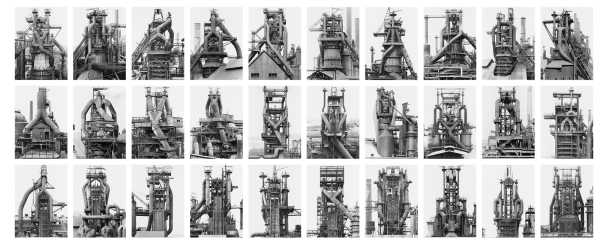

Fuelled by their shared idiosyncratic interests, the Bechers began making pictures together in the industrial areas surrounding Düsseldorf in 1959. They were married two years later. Almost immediately, they landed on a signature style, from which they barely wavered for the rest of their careers. Most recognizably, they used an unwieldy large-format camera to make highly detailed, black-and-white images of isolated pieces of industrial architecture (blast furnaces, water towers, gas tanks, lime kilns, winding towers, and the like) across Europe, the U.K., and the U.S. They presented these structures with lapidary precision, thrown into relief against blank white skies. (Less well known, and less visually striking, are their wide-angled views of factories and the surrounding landscape, also included in the Met’s exhibition.) Early on, the Bechers started organizing their images into typological groups, à la Sander, and displaying them in grids of four, nine, fifteen, or even thirty parts, allowing viewers to compare the sometimes wildly variegated approaches to the construction of utilitarian architectural forms. In a profound testament to their discipline, they captured the items in certain single typologies, such as “Winding Towers (1966-97),” more than thirty years apart. Their somewhat chilly approach—both in subject matter and in style—ran counter to the prevailing humanist bent in the postwar photography world. But their work jibed perfectly with that of the less touchy-feely, systems-based conceptual and minimalist artists who were coming into vogue in New York art circles. The Bechers claimed not to be in the business of courting the art world; Bernd once remarked that their pictures “just happened to fall into this context—for better or worse.” But their place in the Zeitgeist was cemented when they began referring to their photographs with a brilliant coinage that seemed tailor-made for the artistic sensibilities of the time: “anonymous sculpture.”

“Gravel Plants,” 1988-2001.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy The Walther Collection

This bit of conceptual legerdemain functioned as a shorthand for their creative intentions, which were essentially anti-photographic. In 1971, Bernd wrote, “We deal with objects, not motifs. The photograph serves as a stand-in for the object—it is useless as a picture in the conventional sense.” But it was also a canny bit of marketing. The Bechers’ son, the artist Max Becher, recalled that once his parents came up with the phrase, “they kept on repeating that like a propaganda campaign. They really wanted that idea to stick. And it did.” It stuck so well that when the Bechers were awarded the 1990 Golden Lion—the top prize at the Venice Biennale—they were recognized not for photography but for sculpture.

“Cooling Tower, Caerphilly, South Wales, Great Britain,” 1966.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Bechers’ methods involved roaming the industrial hinterlands in a VW bus, lugging around both their bulky camera and stepladders that they used to get the perspective just right, and wrangling permission from the occasionally recalcitrant owners of mills, mines, and factories. Their project was, at its heart, preservationist. The industrial landscapes of Europe and the U.S. were fast disappearing, churned under by the forces of technological advancement, economic stagnation, and the beginnings of global labor arbitrage. The Bechers’ work was far from completist—they were artists, after all, not industrial historians—but the exactitude with which they approached their subjects was a form of respect. Max recalled that they seemed to have “empathy” for the object before their camera, “as if it wanted to say, ‘Here’s my best side. Look at me, I am proud. I am beautiful and I am proud, and lots of people depend on me.” More than once, their reverence proved contagious, spurring efforts to preserve disused buildings such as those in the Zollern mine in Dortmund-Bövinghausen.

“Comparative Juxtaposition, Nine Objects, Each with a Different Function,” 1961-72.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ultimately, the significance of the Bechers’ work rests not on the seductive pull of their individual images, though there is joy and awe to be found in the mind-blowing intricacy and anthropomorphic personality of certain structures they immortalized. Their innovation was to picture the industrial world in a truly industrial manner: exactingly, repetitively, impassively. Despite their feints toward sculpture, the medium of photography imbued their work with an elegant conceptual symmetry: they recorded the remnants of industry using one of industrialization’s most novel tools, the camera.

“Blast Furnaces,” 1969-93.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

One of the Bechers’ students, Andreas Gursky, pulled a similar trick. His massive, digitally altered pictures—of stock-exchange floors, night clubs, luxury hotels, and ninety-nine-cent stores—present the sublime profusion of our postindustrial world with the help of its paradigmatic tool, the computer. Looking at the Bechers’ pictures today, in a world being reshaped by rapid advances in robotics and artificial intelligence, I can’t help but think of the weird images produced by Google’s DeepDream or OpenAI’s DALL-E as an odd continuation of the couple’s legacy. Perhaps the indelible pictures of our new era will be produced by the machines themselves.

“Zeche Hannover, Bochum-Hordel, Ruhr Region, Germany,” 1973.© Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher, courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sourse: newyorker.com