Before he became a photographer, Ara Güler was a projectionist, working the screen at the old Yıldız Cinema in Istanbul. As a young man, Güler enrolled in drama school, inspired by the thespians who once frequented his father’s pharmacy to buy makeup supplies. But it was cinema that helped set the stage for his life’s work. “A photograph, too, has a mise-en-scène,” Güler says in “The Eye of Istanbul,” a 2015 documentary about his life and career. “A photograph has a background.”

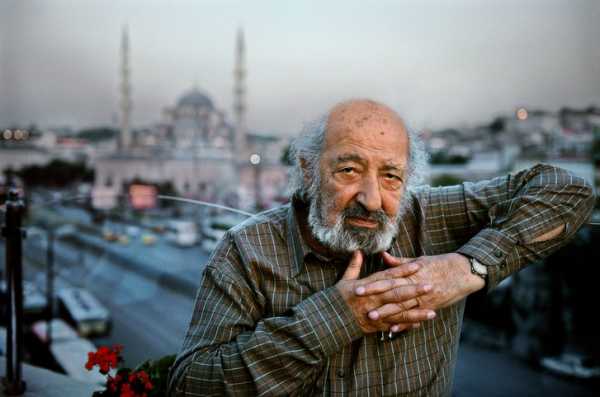

Ara Güler, Istanbul, 2010.

Photograph by Steve McCurry / Magnum

Güler, who lent his affectionate nickname to that documentary’s title, died last week, at the age of ninety. His poignant, majestic archive preserves a vision of Turkey that began to vanish early in his lifetime. In his most famous shots, black-and-white cityscapes from the nineteen-fifties and sixties, couples rush through back alleys flanked by wooden homes. Horses pull carts down cobblestone streets, and skiffs crowd the waters of the Golden Horn, a bustling harbor since Byzantine times. Throughout the twentieth century, Güler’s œuvre interpreted Istanbul for a Western audience without ever exploiting its residents. The Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk, Güler’s frequent collaborator, included the photographer’s images in his memoir, “Istanbul: Memories and the City,” to conjure a picture of a Turkish childhood that words alone could not convey. “When the last brilliant remnants of the imperial city—the banks, inns, and government buildings of Ottoman westernizers—were collapsing all around him, he caught the poetry of the ruins,” Pamuk wrote of his friend, whose work has appeared in New York, at the Museum of Modern Art, and in Paris, at the National Library of France.

The Süleymaniye Mosque, the Golden Horn, Istanbul, 1962.

Born in 1928, to Christian Armenians living in Turkey, Güler began his career at the Yeni İstanbul newspaper, capturing photographs of his cosmopolitan home town. His greatest pride was perhaps the multiculturalism of his family’s neighborhood in Taksim Square. (“I hail from there,” he once said. “Forget nationalism and whatever else.”) As the first Near East correspondent for Time-Life magazine, he endowed the people of Turkey with a dignity that the American media tends to deny those from the region. His portraits revealed the drama and comedy of the everyday, exhuming unsentimental levity from the melancholy, or hüzun, that Pamuk attributed to modern Istanbul. Patient and precise, Güler liked to linger in the city’s Beyoğlu district, near his studio, waiting for daily life to assume the dimensions of a masterpiece. “I wander around and see that a composition is being formed,” he said of his process. “Two men are approaching each other. . . . That’s when I click. I once waited an hour and a half for a cat—just for one cat to pass by. God damn that cat.”

Traffic on the old Galata Bridge, Istanbul, 1956.

Cağaloğlu Hammam, Instanbul, 1976.

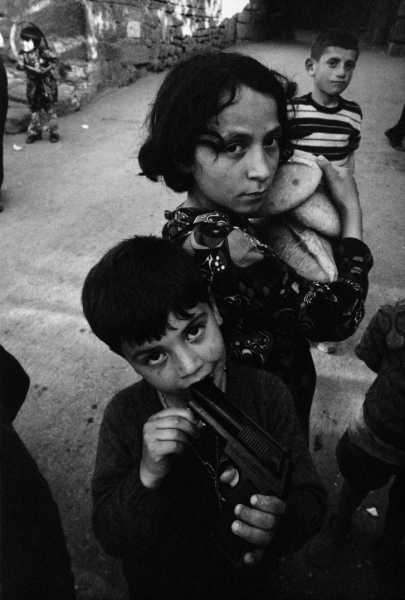

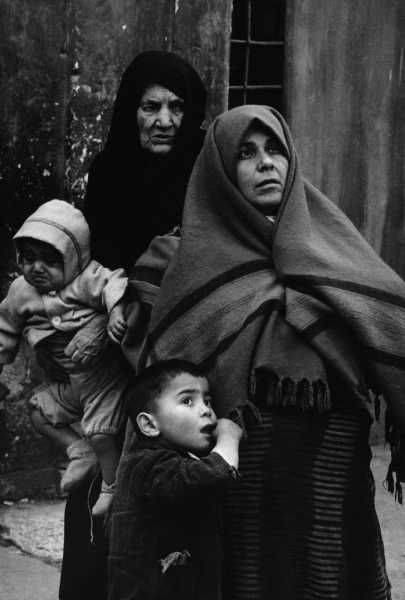

Güler often documented the grit and misery of Turkey’s working class. In one double portrait, a young girl clutches fresh loaves of bread to her chest. The boy beside her, even smaller, eyes the lens with an expectant energy, his mouth clamped on the barrel of a gun. In many images, though, Güler’s youngest subjects evince an optimism that was enshrined in Turkish culture by the country’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who established a national holiday in honor of children. (Turks celebrate this day, Ulusal Egemenlik ve Çocuk Bayramı, on April 23rd every year.) The children cheering in another of Güler’s portraits from the eighties, captured in Istanbul’s Tophane quarter, look anything but benighted. Most raise their hands and open their mouths, their mass rising from the foreground like a bouquet.

Children playing in Tophane, Istanbul, in 1986.

Güler did not consider himself an artist. He preferred to identify as a member of the press, though he conceded that even his most serious work was “a little bit romantic.” In the latter half of his career, he continued to bring an intimate sensibility to the images of Turkey most familiar to outsiders—the white skirts of dervishes, the domes and minarets of mosques, and the palatial chambers of the Cağaloğlu Hammam. Güler was also an obsessive portraitist of some of the world’s best-known artists, performers, and politicians, photographing Sophia Loren, Salvador Dali, Alfred Hitchcock, and Pablo Picasso, who once penned a portrait of Güler inside a book. (Güler never got a shot of Charlie Chaplin, despite camping at the filmmaker’s doorstep for a week.)

Children playing near the old citadel in Ankara, 1970.

The Eyüp Sultan Mosque, Istanbul, 1957.

What united Güler’s work—in Turkey and abroad, even as he aged—was a youthful curiosity that continued to expand his repertoire. In August, on Güler’s ninetieth birthday, a museum devoted to his legacy opened, at last, in Istanbul. Güler’s vast archive contains more than a million negatives, many of them never printed. In the 2015 documentary, we see the photographer’s assistant showing his boss a print of one such image in the days before a show. “Do you remember the moment you took it?” he asks. “Of course I remember,” Güler replies. “Do I look that stupid?”

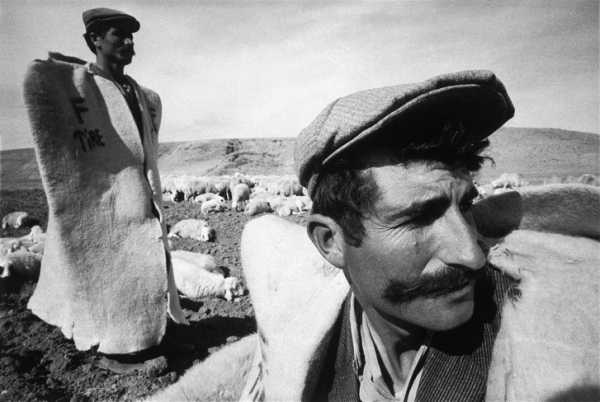

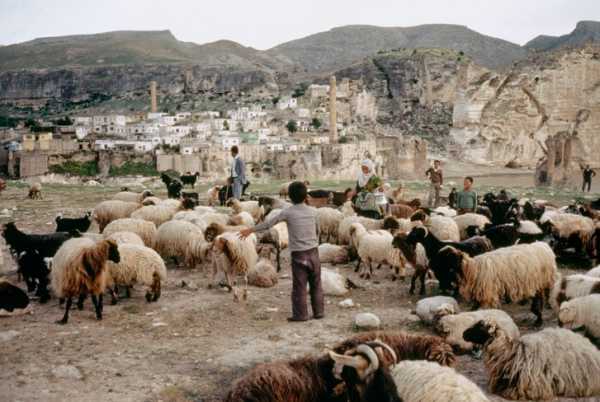

Shepherds near the village of Divriği, Central Anatolia.

The Anatolian plains, 1992.

Istanbul, 1999.

Turkey, 1958.

Sourse: newyorker.com