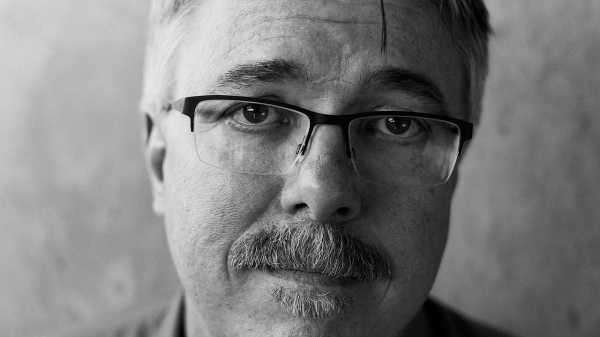

It takes a decent man to create a cruel world. It’s difficult to imagine the fifty-five-year-old Vince Gilligan—soft-spoken, gracious, and exceedingly modest—lasting too long in the violent, bleached-out New Mexico that he put onscreen. The universe of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul,” two of the century’s most highly acclaimed shows, is a place where men become monsters. “It’s like watching ‘No Country for Old Men’ crossbred with the malevolent spirit of the original ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre,’ ” Stephen King once wrote.

Gilligan was born in Richmond, Virginia, and grew up shooting sci-fi films on a Super 8 camera. He went to college at N.Y.U., and soon after graduating, in 1989, with a B.F.A. in film production, he submitted a script called “Home Fries” to a screenwriting competition. The work so impressed the judge, Mark Johnson, who produced “Rain Man,” that he called Gilligan “the most imaginative writer I’ve ever read.” The script became a movie starring Drew Barrymore, and Johnson would go on to executive-produce “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul.”

Gilligan’s big break came in 1994, after years of freelancing for TV shows, when he sold a script to “The X-Files.” He eventually wrote thirty episodes, and became an executive producer. After the series ended, in 2002, Gilligan was “in the weeds for a bit,” before famously persuading AMC to produce a show about a middle-aged, self-deluded schlump who somehow transforms himself from Mr. Chips into Scarface. The result, “Breaking Bad,” turned Walter White into a cultural icon. Gilligan followed it with “Better Call Saul,” which tells another story of transformation: how an Albuquerque lawyer named Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk) becomes Saul Goodman, White’s sly, charismatic, shape-shifting accomplice.

“Better Call Saul” ended earlier this month, completing a fourteen-year journey for Gilligan. A certified free-fall skydiver, as well as a helicopter pilot, he claims that it’s easier “to jump out of an airplane than talk to a stranger.” But, in the course of two phone calls—one before the show’s final episode and one just after—he spoke about a variety of topics, including the origins of “Better Call Saul,” his love for “The Rockford Files,” and (spoilers alert!) the much anticipated ending to a franchise that Anthony Hopkins once compared to a “great Jacobean, Shakespearian or Greek Tragedy.” Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

You once said that you considered the ending of “Breaking Bad” to be, in some ways, a triumphant one. That it was a “victory” for Walt to die on his own terms and provide for his family. Would you say the same for Jimmy McGill?

I’d like to believe that, unlike “Breaking Bad,” “Better Call Saul” has a somewhat happy ending. I think Jimmy rediscovers himself and gets back to his roots. He finds a little piece of his soul again. It gets very dark in the second-to-last episode. It looks as if he’s about to kill one of the sweetest people in the world, Carol Burnett [who plays Marion], and then he rediscovers his humanity. There’s a bit of Dickens’s “Christmas Carol” in it—there’s redemption, of a sort. I don’t think you see that with Walter White.

The further away I get from “Breaking Bad,” the less sympathy I have for Walter. He got thrown a lifeline early on. And, if he had been a better human being, he would’ve swallowed his pride and taken the opportunity to treat his cancer with the money his former friends offered him. He goes out on his own terms, but he leaves a trail of destruction behind him. I focus on that more than I used to.

I rewatched the entirety of “Breaking Bad” recently. My love for Walter White has dissipated. And my love for Skyler White has only grown.

After a certain number of years, the spell wears off. Like, wait a minute, why was this guy so great? He was really sanctimonious, and he was really full of himself. He had an ego the size of California. And he always saw himself as a victim. He was constantly griping about how the world shortchanged him, how his brilliance was never given its due. When you take all of that into consideration, you wind up saying, “Why was I rooting for this guy?”

Back when the show first aired, Skyler was roundly disliked. I think that always troubled Anna Gunn [who played Skyler]. And I can tell you it always troubled me, because Skyler, the character, did nothing to deserve that. And Anna certainly did nothing to deserve that. She played the part beautifully. I realize in hindsight that the show was rigged, in the sense that the storytelling was solely through Walt’s eyes, even in scenes he wasn’t present for. Even Gus, his archenemy, didn’t suffer the animosity Skyler received. It’s a weird thing. I’m still thinking about it all these years later.

I know there were alternate endings discussed for “Breaking Bad” in the writers’ room: Walt would die in a hospital hallway with no one recognizing who he was; Walt would survive but his immediate family would all perish. What were some of the alternate endings discussed for “Better Call Saul”?

This ending always seemed fitting to me: that Jimmy, the lawyer, pay the price in terms that were fitting to his career choice. In other words, it seemed right that he go to prison.

Walter White escaped prison by dying in a hail of bullets. Jesse Pinkman, I like to think, got away with it, although he obviously didn’t get away with it. He went through far worse tortures than any penitentiary could offer—being enslaved and made to cook meth by a gang that was holding him hostage. So you have Walt’s ending and Jesse’s. There’s got to be a third ending—you can’t repeat either of the first two. I don’t think we ever really thought about Saul Goodman dying at the end. The character Lalo kept calling Saul a cockroach. And what do cockroaches do? They survive. It never seemed even a remote possibility that he die. That would’ve felt unearned.

There was fear among fans that Kim Wexler, Jimmy’s ex-wife, would see a grisly end.

We strung people along. Fans would say, “Oh, my God, you’re not going to kill Kim, are you?!” And Peter [Gould, the show’s co-creator] and I would look at each other and shrug. We’d say, “You have to watch.” But we never, ever thought about killing off Kim. Rhea Seehorn is just so delightful. We wouldn’t have wanted to do the show without her. I can’t say her character, Kim, was always delightful, because she does some pretty horrible stuff in that final season. But she, too, comes to her senses.

True. Then again, Kim’s boyfriend is a dud who rhythmically grunts “yup” while having sex.

Yeah. Life’s never going to be perfect. By the way, as we see in that final episode, Kim is making some subtle but important life changes. She goes and volunteers at the Legal Aid Society. So Glenn, her boyfriend—he seems like a likable chap, but I don’t know that he’ll last in this new world she’s going to create for herself. I don’t know if he’s going to be allowed to stick around.

It’s fun to think about what happens when we won’t be watching. It’s almost like a Sims world, in which the characters continue on without us knowing exactly what they’re doing.

I tell you, that’s about the nicest thing I’ve ever heard anybody say about this. The characters really did feel alive to us. On our best days in the writers’ room, it felt like we were transcribing rather than creating. And I felt that way on my best days on the “The X-Files,” too. I’d sometimes hear Mulder’s and Scully’s voices in my head, and I felt like a court stenographer. That, to me, is when it’s really working.

What are Kim and Jimmy doing now? What’s next for them? I think it’s a wonderful thing when the fans feel that way, because you give this story over to the folks who watch it, and it becomes theirs. The thought that fans are still living with these people in their daydreams—that makes me very happy.

You’ve always been quick to give credit to others on your production staff. Outside the business, one doesn’t often hear about this collective effort.

This auteur theory that the French gave us, God bless them, was always bullshit. There’s this romantic notion that there’s only one director or showrunner behind every great movie or TV show, but that’s just not the case. I suppose it’s theoretically possible, but only on the smallest independent movie. Even then, if you’ve got a camera person and a sound recordist and actors, you’re not doing it all yourself. The auteur theory, it just doesn’t hold a lot of water. It doesn’t stand up in court.

It really took a village to make both of these shows. I know Peter Gould would agree. Editors, directors of photography, actors, hair and makeup, the caterers who feed us, the list goes on and on.

There are many indelible images in “Better Call Saul,” but one of the most haunting, for me, was Lalo Salamanca and Howard Hamlin ending up in the same pit, dead, within Gus Fring’s future underground lab. It seemed to suggest that, whether you’re good or bad, moral or immoral, you could still end up in basically the same situation.

I guess that’s true. By the way, we could do an hour-long interview just on how fucking hard it was to build that pit. We had to dig into the floor of the soundstage and get structural engineers involved and all kinds of stuff. It was a big deal.

Here I am looking for a moral. For you, the creator, it’s more about logistics.

Peter and I and the writers come up with stuff, and that’s the easy part. And then the crew makes it real. They spent a lot of blood, sweat, tears, and money building what looks like a giant hole in the ground, when in fact it’s on a soundstage, and made out of Styrofoam and plaster. Then we realized we needed to put another hole underneath all of that! That became the source of a great many meetings. Finally, the studio let us get engineers in there, and we actually cut a six-foot-deep hole into the concrete floor of the soundstage, which was no small feat. To reiterate: the auteur theory is bullshit.

Does that come into play when you write scripts? Balancing your initial vision with the reality of what’s possible on set?

It should come into play. It often doesn’t. It didn’t with me early in my career, which is why I think it’s good advice for writers to learn to think as producers and directors. Then they wouldn’t get their hearts broken quite as often by writing material that’s absolutely impossible to shoot. I remember the very first episode of “The X-Files” I wrote [“Soft Light,” Season 2, May 5, 1995]. I was a freelancer. I wrote this episode that would’ve cost, I don’t know, forty or fifty million dollars to make, back when our budget was around five or six million. I just didn’t know any better. I was a dipshit writer who had no experience in terms of production. So, yeah, writers should be thinking of that.

Is this one of the mistakes you see in young TV writers?

Yeah, but that’s O.K. I’ll read scripts from time to time where I say to myself, “This writer has never been on a film set.” But that doesn’t automatically disqualify them. If you can tell a good story, it’s O.K. if you happen to have written a script that is impossible to produce. And really nothing these days is impossible to produce, given the advent of digital effects. At the end of the day, all that really matters is that they told an entertaining story. The rest of that stuff can be taught.

You’ve said that one of the advantages to writing television is that characters can change during the course of a series, which is less possible in film. Can you give me an example of a character from “Better Call Saul” who changed over time?

When I look back at the first two episodes of “Better Call Saul,” I realize we didn’t know that much about Jimmy McGill. And we knew even less about his brother Charles McGill and his boss Howard Hamlin. Peter and I and the writers were convinced that Howard Hamlin was going to be the bad guy. And we were convinced that Chuck was going to be this Mycroft Holmes [Sherlock Holmes’s older brother] kind of character who was emotionally damaged but very supportive. That was the original plan.

Then it began to morph, because we had the benefit of all that time in the writers’ room and, even more important, the benefit of watching these actors play these roles. So we came to realize, Wouldn’t it be more interesting if Howard—who looks like the bad guy because he’s so polished and handsome and seems to be the king of the world—is not as bad as he appears? And what if Chuck isn’t as supportive of Jimmy as we first think he is? How might he really feel about his younger brother, a correspondence-school lawyer? He’s neither the good guy nor the bad guy in the final estimation, but he’s definitely not in his brother’s corner. When we realized that, the show got so much more interesting.

There was an edge to the way Michael McKean was playing Chuck McGill that we found tremendously interesting and fun to watch. It led us to realize that maybe there’s more to this character than just a brilliant attorney who thinks he’s allergic to electricity.

“Fifteen years ago, when I was conceiving of Walter White, I looked around and thought, Well, what is current TV? It’s mostly good guys,” Gilligan said. “But now I’m looking around, thinking, Gee, there’s an awful lot of bad guys on TV, and not just on shows but on the news.”

That you’d follow the lead of the character rather than vice versa says something about you as a creator.

If there’s any secret to our success, I think it’s that. The TV shows we love are populated by characters who seem real to us. We don’t have to agree with them, but we get where they’re coming from. We comprehend them on an emotional level.

But you can’t do that by forcing them like square pegs into round holes. It sounds kind of artsy-fartsy, but you’ve got to listen to them. By that I mean you’ve got to be honest about what they would do next in any given situation. It was much more rewarding for us in the writers’ room when that kind of thinking led us to realizations such as Chuck’s resentment of his kid brother.

Sometimes, that takes you to some very unexpected plot destinations. Some of our very best ideas came at the eleventh hour, many seasons into both shows. In hindsight, I like the way we did it. The longer it took, the more nervous it made us that we didn’t have a clear road map. But we found our way. It was a struggle, but we purposely didn’t know how things were going to end at the beginning. We didn’t even know halfway through, probably.

One of the things I love about “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul” is what’s not written. I suppose that, too, is a sign of good writing. Nothing is overexplained.

When I first started writing, I was as guilty as anybody of editorializing. I had this fear of “Gee, the audience won’t get it.” I felt I had to explain all this stuff. . . . But eventually you learn to relax. You realize you can learn just as much from a character by what they don’t say.

The main blessing of binge-viewing, I think, is that it accommodates serialized storytelling. It also allows writers to incorporate a great deal of detail that gets picked up on by attentive viewers. This ability to watch episodes one right after the other has allowed for a kind of storytelling that really wasn’t available twenty years ago. When I was on “The X-Files,” you had to make episodic shows because people didn’t time-shift like they do now. I mean, people had VCRs, but it was a chore to put the tape in and set the timer and all that. Fans often missed more episodes than they saw. Consequently, it was harder to evolve a television character because you didn’t have the ability to see them changing week to week like you do with streaming. It was just the nature of the medium, but the medium changed. To me, that’s a nice evolution.

That’s interesting. In “The Rockford Files,” say, the character of Jim Rockford wouldn’t change all that much in the course of a season, or even multiple seasons. Perhaps there was a sort of comfort in that lack of change.

Yeah, there’s a real pleasure to watching shows like that. Honestly, that’s all I watch these days. I love the old stuff. I love old episodes of “Emergency!” and “The Rockford Files” and “Columbo” and “The Twilight Zone” and “Hogan’s Heroes.” It’s comfort food for my brain. I hope that kind of storytelling never goes away.

For my next show, I’d like the lead character to be an old-fashioned hero, an old-fashioned good guy. Jim Rockford is kind of rough around the edges, but he always does the right thing. Fifteen years ago, when I was conceiving of Walter White, I looked around and thought, Well, what is current TV? It’s mostly good guys. But now I’m looking around, thinking, Gee, there’s an awful lot of bad guys on TV, and not just on shows but on the news. It feels like a world of shitheels now, both in fiction and in real life. I think it’s probably time again for a character who doesn’t go for the easy money. I’d be very happy if I could write a more old-fashioned hero, someone who is not out for themselves at every turn.

Both “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul” are set in New Mexico. What did you know about that landscape before you started work on the shows? You grew up across the country in the South.

I got really lucky that the production guys at Sony said to me, when they read the pilot episode of “Breaking Bad,” “What do you think about shooting it in Albuquerque?” And I said, “Well, guys, as it says on the page, I set it for Riverside, California, the Inland Empire.” They said, “Yeah, we get that. But New Mexico has this rebate they’re giving filmmakers. It’s a much sweeter deal financially than anything Southern California’s going to offer us. And the reason that’s good for you is you effectively have a larger budget with which to make your show.”

I thought, Yeah, but really it should be California. Because that’s what I had in my head. But then I realized the sad truth is that there’s a meth business—many of them, in fact—in all fifty states. So I thought, Why not New Mexico? It was a very meat-and-potatoes, dollars-and-cents decision. And it turned out to be the greatest thing creatively. We did save a lot of money over the years, but the best thing about that decision was that it allowed us to shoot in this amazing cinematic landscape in and around Albuquerque. It’s a very striking, beautiful place, and it makes me think of all the great Westerns I love. All the John Ford Westerns. All the Sergio Leone Westerns—actually, those were shot in Spain, but it’s amazing how much the Spanish desert in those movies reminds me of the New Mexican desert. It was a great boon to us when we realized, “Hey, we can make this thing a Western, a contemporary Western.” The show wouldn’t be the show without New Mexico.

How do you view the “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul” characters within the realm of good versus evil? It’s not as clear-cut as it was in the classic Westerns of the nineteen-fifties, or even in the postmodern Westerns of the seventies, eighties, and nineties.

A critical-studies professor would give you a much better answer to this. But, when I think of a Western, I think of a character, either a protagonist or an antagonist, making their way through an essentially lawless land and imposing law of some sort onto that landscape. That, to me, is why Westerns remain so enjoyable. The idea of an individual imposing a structure upon an essentially structureless place is embodied in “Breaking Bad” in one of our main characters, Hank Schrader. He represents honor; he’s the sheriff, so to speak.

But the subculture in which Walter White finds himself, in which he has placed himself, is the lawless landscape of criminality that is the Albuquerque underworld, and that’s the Wild West part. If you lived on a frontier that did not have structure, that didn’t have law and order, that didn’t have these things we take for granted now, it’s incumbent upon you to impose structure. In the old John Wayne Westerns I love, the Duke is the good guy dispensing law and order in a lawless land. But the bad guy can do this, too. And it could be argued that a bad guy is more interesting. Either way, the idea of a main character imposing structure however they see fit is fascinating to me.

Going back to your first question, Howard Hamlin is basically a good guy. He’s not a saint, but, yeah, he winds up in the same pit as one of our most chaotically evil characters, Lalo Salamanca. And I guess you could say, “Oh, this speaks to the randomness of the universe.” Writers love irony, and I guess it’s ironic that they wind up in the same grave. But, to me, there’s no message there. That’s not us saying, “Give up trying to find meaning in the world. Everything is meaningless.” I think there must be a meaning to this life. Please don’t take away that it doesn’t matter how you live, good or bad. That is definitely not our message. Although it turned out that way in the case of Howard and Lalo, chaos and anarchy are not what we’re selling.

Well, there has to be some sort of message, right? Otherwise, why write it or even shoot it? Don’t all stories have to contain some theme?

You know, one of the smartest things anyone ever said to me in this business came from Michael Mann, a brilliant writer, a brilliant director. I was hired to do a rewrite on what was already a really good script. It was the early days, and I’m saying to him, “O.K., so what’s the message? Thematically, what are we doing?” All that film-school bullshit. But I honestly wanted to know. I wanted to pick his brain and ask him, “What are we trying to say here?”

He listened very patiently. I forget exactly the words he used—I wish I could quote him verbatim. But essentially what he said was “It’s your job to write an entertaining story. It’s your job to come up with a script that inspires the actors and director. And then, hopefully, this work will be viewed by moviegoers, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, wow, that was interesting. I didn’t see where that was going. I like the twists and turns. I like the characters.’ ” He said, “That’s the job, period. The froufrou thematic stuff is for other people to figure out. The college professors. All you have to do is tell an engaging story.” And he was right.

That’s why interviews like this are dangerous, because I tend to wax on about, “Gee, this is what it really meant.” And I’m just as full of crap as anybody. I’m probably less able to tell you what it all means than someone else who’s looking at it from a distance. What I can tell you is that a lot of the stuff people read into these shows was stuff that was not on our minds when we made them.

It’s really up to the viewer. The folks who write and direct and act and build the sets and feed the crew? They’re crucial to the process. But the fans have a job, too, because if there weren’t any viewers the whole exercise would be pointless. It’s the viewer’s job to discover what it all means. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com