Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Anaheim, the most populous city in Orange County, got its name from German settlers who moved south from San Francisco after the 1846-48 war against Mexico, which led to the annexation of California by the United States. (The name combines the German word for “home” with the name of the Santa Ana River.) Spaniards and Mexicans were themselves colonists who had taken the land from its previous inhabitants, the Tongva and Acjachemen. Today, Anaheim, about thirty miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles, is best known as the home of Disneyland, the Los Angeles Angels baseball team, and the Anaheim Ducks of the National Hockey League. The photographer William Camargo, who was born and raised in Anaheim and now lives and works there, recovers the city’s Indigenous and Mexican past and present by documenting the places and people just beyond the walls of the theme park.

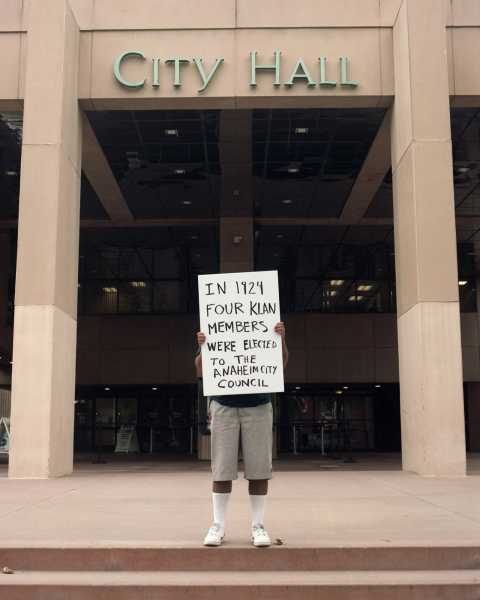

In a series called “Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories, and Possibilities,” Camargo stands at seemingly unremarkable sites where he holds up signs that tell an alternative history of Anaheim. Anaheim High School’s mascot is the Colonists. In one of Camargo’s photos, he stands in front of a “Home of the Colonists” sign painted on to the school’s wall, with his own sign that says “This is Tongva and Acjachemen Land!!” At Pearson Park, amid towering trees and dramatic afternoon shadows, Camargo holds a sign that reads “This park used to be segregated.” The Anaheim Packing House, which was built in 1919 and used by Sunkist, is now a fashionable food court. In another photo, Camargo holds a sign in front of the building that says “Brown women used to pack oranges here.” At Anaheim’s City Hall, his sign reads “In 1924 four Klan members were elected to the Anaheim City Council.” (They were all forced out in a recall election the next year.)

From top, Benjamin, Efren, Jose, and Edgar sit for a portrait in their Anaheim neighborhood, which borders Disneyland.

Cielo Elda in a traditional Durango ballet folklórico dress, in George Washington Park in Anaheim.

The photo in front of City Hall, in particular, sparked controversy at the Muzeo Museum and Cultural Center, where an exhibition of Camargo’s work appeared in 2020. Katie Adams Farrell, the museum’s former C.E.O. and executive director, told me that, after discussions among staff and board members, who feared that in the tense national racial climate that summer there would be a backlash to the photos, the museum made the decision to move the image from a window facing City Hall to a semi-open foyer. “I felt that the board’s hesitation was because they didn’t want to confront Anaheim’s history straight on,” Camargo told me, “but I ultimately was fine as long as they showed it instead of not showing it at all.” (The current executive director of Muzeo, who was not employed there at the time of the exhibit, said that board members recalled it as “a very successful display” and that “no one was aware of any discussions regarding placement.”)

Camargo stands with a sign about the previous workers of the Anaheim Packing House.

Camargo stands outside the Anaheim City Hall with a sign noting that four members of the Ku Klux Klan were elected to the city council in 1924.

As a child, Camargo practiced soccer at Pearson Park twice a week. The Anaheim Packing House, which was empty when he was young, was “where you would see people shoot up,” he said. “These are some of the places I would pass by or play in as a child, but I didn’t know what had happened there.”

From left, Jose, Benjamin, and Efren stand outside a friend's apartment near Disneyland. Their friend waves a gun from behind a curtained window in hopes of scaring them.

After receiving a bachelor-of-fine-arts degree from Cal State Fullerton, Camargo moved to Chicago, where he worked as a photojournalist for the Chicago Reporter. He returned to Anaheim in 2018 and enrolled in an M.F.A. program, at Claremont Graduate University, where he worked with Ken Gonzales-Day, an interdisciplinary and conceptual artist best known for his ongoing “Erased Lynchings” series, a project that documents the neglected killings of Mexican Americans, Native Americans, and Asian Americans in the American West and California in particular. At C.G.U., Camargo learned about artists like the members of ASCO, an avant-garde Chicano art group that was most active in the nineteen-seventies and eighties, and the late Chicana photographer Laura Aguilar, who used signage in her work in a way that influenced Camargo. When Camargo moved back to Anaheim, he began to research the history of his home town. The places he visited as a child “must have a history,” he thought. He learned that it wasn’t necessarily a nice history, but, he said, it was “one that I think we should recognize.”

Angie and Nayeli Monreal at Ponderosa Park in Anaheim.

Aurelio Vargas wipes his face after having a traditional Mexican soup on a hot summer day in Anaheim.

In the images that make up the “Origins & Displacements” series, the signs that Camargo holds cover his face, reënacting the erasure of the city’s Mexican heritage, and downplaying his own subjectivity in order to highlight the history he’s trying to tell. At the same time, he wears Nike Cortez sneakers, a Baja hoodie, and Dickie’s shorts or rolled-up jeans, in order to signal his Chicano aesthetic. His presence in the images, and his recovery of Anaheim’s Indigenous, Mexican, and Mexican American history, is part of what he describes as a move toward a post-colonial Los Angeles shaped by “Chicano futurism,” which, for him, means a desire to write new histories of Anaheim that are present- and future-oriented.

Camargo told me that the “signage work” in “Origins & Displacements” is “very direct and confrontational.” He had a clear message to deliver. But Camargo also captures the humanity of the Mexican Americans who’ve lived in Anaheim for decades, including his own family members. One photo, “Getting That Rasquache Haircut,” shows his brother cutting his father’s hair, holding his head in place as he runs over his scalp with clippers. His father’s eyes are closed, and his facial expression is restful. Another, “More Work After Work,” shows his mother, an employee at Northgate Market, a local grocery-store chain, with her back to the camera, washing dishes in a kitchen illuminated only by a curtained window. When his father first saw the photo of him getting a haircut hanging in a gallery, he asked his son why anyone would be interested in seeing it. But now, Camargo says, his father understands that there aren’t many pictures of people who look like him hanging in galleries or museums: “There’s an absence of these kinds of moments in these places.” Camargo told me that it took about a decade for his father, who, like many other Latino parents, wanted his kids to become doctors or lawyers, to realize, “oh, this is why he chose photography as a career, and why he wants to tell this story.”

Esperanza Camargo washes the dishes at her home, in Anaheim, during the coronavirus pandemic.

José Camargo gets a haircut from his son Osbaldo in their back yard during the coronavirus pandemic, in 2020.

Camargo stands in front of a planned construction area for town homes in a working-class neighborhood of Anaheim.

Sourse: newyorker.com