The photographer Tommy Kha grew up in the Memphis neighborhood of Whitehaven, the home of Graceland, absorbing the complex vitality of Elvis Presley fan culture. Its traditions of reënactment and impersonation (Kha notes that the preferred term for participants is “Elvis tribute artist”) are evident in such Kha works as “Constellations (VIII),” a dreamy collage-like self-portrait from 2017. In it, Kha appears unsmiling in a nineteen-fifties kitchen, wearing a white jumpsuit inspired by Presley’s costume for the 1973 concert “Aloha from Hawaii.” The room is turquoise with tomato accents, furnished with vintage appliances and a battered steel filing cabinet. As in many of Kha’s pictures, a tenderly sunlit strain of Lynchian surrealism brings his themes of dislocation, domesticity, identity, and masquerade into gorgeous, supersaturated relief.

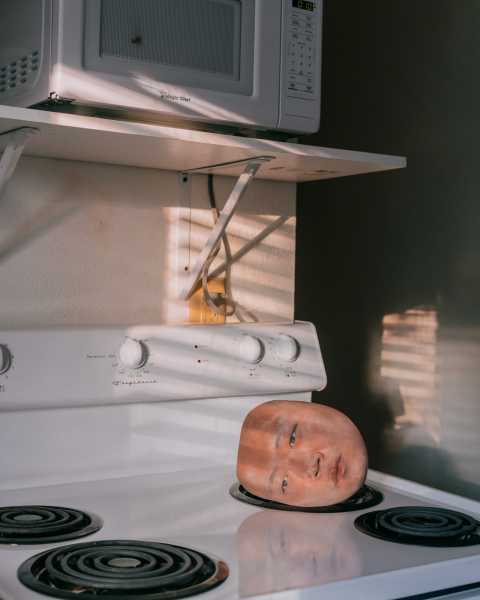

“Headtown (XII),” midtown Memphis, 2021.

“Exchange Place (VI),” midtown Memphis, 2019.

Last February, “Constellations (VIII)” was mounted as part of a public group installation at the Memphis International Airport. Then the owner of an Elvis tourism store shared the image on social media, disparaging it as a “joke,” and prompting a slew of complaints from self-appointed arbiters of Elvis’s legacy, many of them overtly racist. (“The Chinese bought the airport too?” one person said.) The airport caved under the negative attention and removed the work, then quickly reinstated it thanks to an opposing outcry. But the incident illustrated a Catch-22 for Kha as an Asian American artist engaging with an icon of Americana, no matter the notes of irony and melancholia in his self-depiction. Who gets to play with Elvis’s image? Even in the realm of sequinned fantasy, segregation and exclusion are enforced.

Kha’s subject matter is more directly autobiographical in the ongoing collaborative series “Má,” which he began a decade ago with his mother, May, who still lives in Memphis. (The title is a Vietnamese term for “mom.”) Through the simply staged but lush and nuanced vignettes, Kha elaborates a formidable and complicated connection between mother and son. At the Dumbo gallery Higher Pictures Generation, an exhibition of six of these images, made between 2015 and 2021, shows that the pair has found a winning balance between deadpan absurdism and formal acuity.

“Headtown (V),” Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017.

“May (Mirror, Mother, Mirror),” Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019.

“May (Betwixt),” Whitehaven, Memphis, 2015.

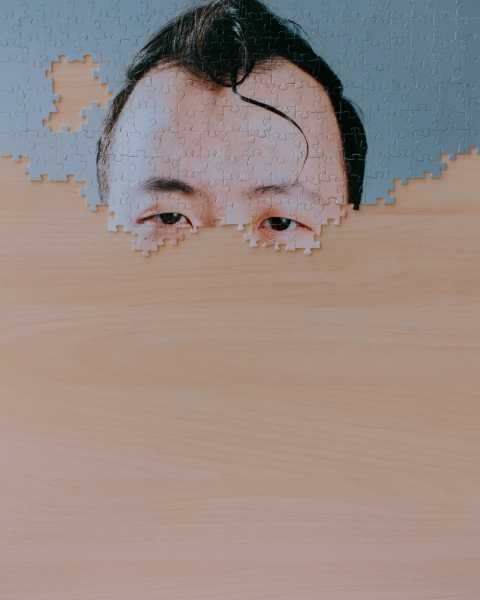

In the striking “May (Betwixt),” from 2015, May appears in a hallway, a small figure in blue reclining on an orange carpet; only her head, nestled on one arm, and her shoulders are visible, emerging from a doorway. She seems to rest on the stripe of light that escapes from the room as she regards the camera with patience, maybe boredom. The cropping of her figure echoes the fragmented approach that Kha uses elsewhere to imagine or project impossible scenarios, as with his photo-printed cutouts or 3-D masks of his own face. A similar effect is achieved with a timeless trick in “May (Mirror, Mother, Mirror),” in which his mother’s inscrutable expression, tightly framed in a small hand mirror, is isolated, and almost overwhelmed, by an expanse of wood-panelled wall.

“May (A Costume Drama),” Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019.

“May (A Costume Drama)”, from 2019, shows Kha and his mother together, in a living room, wearing serious expressions and what appear to be moisturizing facial sheet masks. An additional layer—drawn-on eyebrows, and a mustache on Kha that evokes yellowface caricature—fills this intimate interior scene with acid commentary. Kha’s project poses interesting questions about power dynamics, which are as endemic to families as they are to the medium of photography; it’s telling that, in this image, it’s the stern May who controls the camera’s shutter release, conferring a certain authority.

One could not accuse the duo of whimsy—that’s not the mood here at all. Yet, while the protagonists of “Má” exist relatively invisibly in the orbit of Graceland, they are not so unlike Elvis tribute artists who flock to it. In these charming, forceful images, self-invention and camp pageantry reign.

“Assembly (I),” Brooklyn, 2018.

“Mine (VII),” Twentynine Palms, California, 2017.

Sourse: newyorker.com