My thoughts about the best developments in art this year are eclipsed by my grief for the worst: the death, in October, of Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker’s longtime art critic. Peter’s superb prose was informed by his early days as a poet, and his use of language was as edifying as it was pleasurable. (Rereading his year-end take on 2008, I just relearned the word “pertinacious.”) But, unlike the voices of some master stylists, his never ossified into glibness. He always hoped to be surprised by a work of art, not to have his preconceptions confirmed. “The job of an artist is not to make you comfortable with your ideals,” he once said. In the late seventies, around the time he was shedding his poet’s skin to devote himself fully to criticism, he made a note to himself in a catalogue’s endpaper, laying out his principles: “I try not to think about what I will write, try to keep myself pried open. My nemesis is the veer into mere headiness, where ideas propagate fecklessly. . . . I try to chasten my intellect with the effort of attention, which in intellectual terms is doubt—doubt being the certainty that you’re always missing something.”

2022 in Review

New Yorker writers reflect on the year’s highs and lows.

In our current art world, the certainty of missing something has become inevitable. One contributing fact is that the connoisseur class, collectors and museum curators alike, insist that the art-fair circuit—essentially a farcically far-flung and fast-paced shopping spree—is a vital context for art. In 2022, galleries schlepped their wares to fairs in Basel, Dubai, Hong Kong, London, Miami, Paris, and Seoul (a very incomplete list). Six landed in New York City in May, with five more stuffed into the already hectic first week of September, the official kickoff of the new art season. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is “goblin mode” (whatever that means), but, for this manic pursuit of blue-chip trophies and next big things, I’d swap in a phrase coined by Schjeldahl, years before the scene reached its current warp speed: “festivalist slambang.” You don’t have to pay attention to fairs to feel overwhelmed by what you won’t see. Per a study commissioned by the de Blasio administration, in 2015, there are some fourteen hundred galleries in the five boroughs, not to mention scores of museums. Following are a few highlights of my hyperlocal year in the trenches.

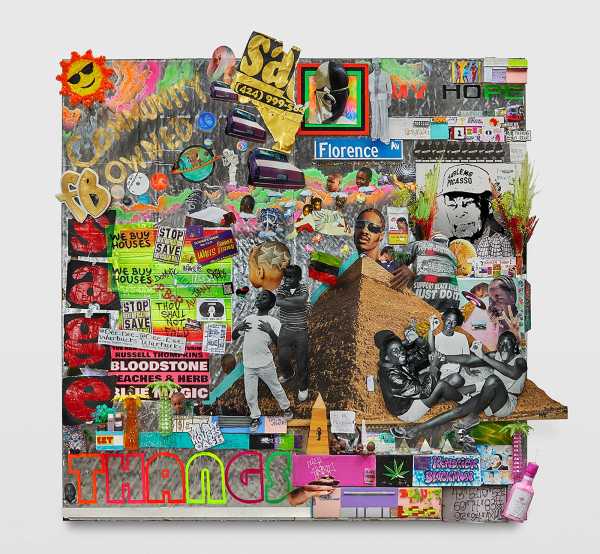

“thou shall not fold,” 2022.Art work by Lauren Halsey / Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery; Photograph by Allen Chen / SLH StudioLauren Halsey at David Kordansky

Hands down the most exciting gallery show I saw this year was the New York solo début of this wildly talented Los Angeles sculptor, whose muse is South Central, the historically Black neighborhood that her family has called home for close to a century. The fourteen pieces on view ran the gamut from towering columns to encrusted grottos, all brimming with references to local businesses (the Braid Shack, Watts Coffee House) and fallen heroes (Kobe Bryant, Nipsey Hussle), as well as such cultural touchstones as ancient Egypt, Jet magazine, and Afrofuturism. Not for nothing did the P-Funk legend George Clinton call Halsey one of his favorite artists. Next year, she supersizes her vision on the rooftop of the Met—a guaranteed best of 2023.

Celia Vasquez Yui at Salon 94

A much quieter show than Halsey’s, but, in a sense, just as epic. A member of the Shipibo people of the Peruvian Amazon, Vasquez Yui is a ceramicist working in a matrilineal tradition reaching back thousands of years. If the arrangement of her exquisite zoomorphic sculptures—anacondas, armadillos, caimans, capybaras, jaguars, monkeys, parrots, river dolphins, red squirrels—called to mind a ritual gathering, the image was not accidental. The Shipibo believe that the intricate patterns decorating each piece that they make emit healing vibrations.

The Secret Keepers

I’m not sure that New York City’s mini-trend of unannounced shows and word-of-mouth spaces is a direct response to the corporate bloat of the art world’s mainstream, but it certainly felt that way to me. Mister Fahrenheit is literally an underground gallery, situated in a former subterranean swimming pool behind a town house in the West Village. It maintains public hours, but if you visit you’re bound to have the space to yourself, as I did this summer for Gedi Sibony’s tenderly dramatic installation. I spent a delightful afternoon at Club Rhubarb this fall, an invitation-only space whose neighborhood I can’t disclose (but might be able to soon). Even the venerable Marian Goodman is in on the act. Last year, she crammed a small space full of works by the Mexican sculptor-conceptualist Gabriel Orozco. I didn’t get wind of it until this summer. On the occasion of Orozco’s MOMA survey, in 2009, Peter Schjeldahl deemed him “easily the best artist to have emerged on the era’s global biennial circuit.” Judge for yourself; the show is up through next summer.

“An Introduction to Nameless Love,” 2019.Art work by Jonathan Berger / Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art; Photograph by Ron Amstutz“The Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept”

The curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards orchestrated the most cohesive and eloquent biennial in recent memory, using an ingeniously simple two-part structure. The sixth floor was largely divided into dimly lit spaces; meanwhile, on the sunlit fifth floor, almost all the interior walls were removed. In less deft hands, this might have yielded something dualistic, contrasting, perhaps, the shadow side and the interiority of the pandemic against its bright spots, such as the groundswell of collective activism. Although there was no shortage of works touching on either personal loss or public politics, the show was gratifyingly nuanced—not least in its border-expanding, history-rectifying definition of what an American artist is.

“Matisse: The Red Studio” at MOMA

More than simply the best museum show of the year, which it was, this jewel-box exhibition was also a once-in-a-lifetime lesson in the rewards of narrow focus. The polar opposite of an art fair? You bet. It reunited a masterpiece by the French painter, from 1911—a Venetian-red rendering of Matisse’s studio in Issy-les-Moulineaux—with all the surviving works by the artist that it depicts, an event that is unlikely to be repeated. Forget the so-called immersive exhibitions. (Van Gogh, I’m looking at you.) The six paintings, three sculptures, and one ceramic plate installed near, but never crowding, “The Red Studio” brought a familiar picture thrillingly to life. By contrast, profiteering digital sideshows put art to death.

“Round Hill,” 1977.Art work © Alex Katz / ARS; Photograph © Museum Associates / LACMAAlex Katz at the Guggenheim

This triumphant eight-decade survey caught me off guard. I’ve often found the paintings of this native New Yorker wonderful, but never profound. I may have been biased by the way that Katz’s images have circulated in the culture at large, flaunted as signals of urbane detachment, whether it’s a colorful cocktail party in the opening credits of a movie by Neil LaBute, from 1998, or a bright-yellow double portrait, which became Instagram famous as the cover of a recent Sally Rooney novel. But, as I tracked the progress of this ninety-five-year-old artist up the Guggenheim’s ramp, what struck me, even more than his mastery of light or the deceptive ease of his flat surfaces, was a devotion to painting so intense that there is only one word for it: love.

Sourse: newyorker.com