Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

It’s a law of nature: every year brings a gust of theories about Vincent van Gogh. His life has been scrutinized for so long that we seem to have all the information, and nowhere near enough. Sturdy truths have been almost-replaced by almost-facts: he cut off his ear, unless he cut off only the lower half, unless Paul Gauguin did. He shot himself, unless he was shot. With these biographical blurs come uncertainties about the paintings—is “Wheatfield with Crows” really a kind of suicide note? Is it even sad? Scholars have shown that it wasn’t van Gogh’s last work, and it may not have been his second- or third-last, either. If we keep this up for a few more decades, we won’t know a single thing about him.

You could say that we’re drawn to van Gogh because his life crackled with complexity. You might also say that this is putting the cart before the horse—that any life or object, no matter how ordinary-seeming, contains multitudes, if we bother to look. This happens to have been the premise of van Gogh’s art. The plainer his subject, the more he found. “When the object represented is . . . at one with the way it is represented,” he wrote in June, 1889, “isn’t that what gives a work of art its quality?” Here and elsewhere in his letters, he doesn’t sound as though he’s making things look a certain way. He’s just reporting, with a sort of scientific rapture, on how they really are—exaggerating the essential, as he put it.

“Van Gogh’s Cypresses,” a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is the latest attempt to look at a single object as deeply as the artist did. Its cousins are 2015’s “Van Gogh: Irises and Roses,” also at the Met, and 2021’s “Van Gogh and the Olive Groves,” which launched at the Dallas Museum of Art. It’s as though museums are trying to treat the kitschy generality of van Gogh’s mystique with an emergency dose of narrowness, zooming in on his rough, impasto work for clues to his genius. There’s plenty to choose from. Clouds? He can make them look like bubbles wobbling through water, or dry yellowed bones. Moons? He painted and repainted them as though whittling, trying to get the curves and sharp crescent points just so. Poplars, gardens, bridges, peasants, wheat fields—curators could stand in front of almost any van Gogh, close their eyes, point a finger, and turn what they land on into a blockbuster exhibition. Which means that the question stalking “Van Gogh’s Cypresses” isn’t “Why those?” It’s “Why especially those?”

Even by the standards of van Gogh studies, the curator Susan Alyson Stein has made a scarily thorough case. Visitors who dare to doubt that the artist had cypresses on his mind will be sternly corrected a hundred times. The show is a week-by-week, almost day-by-day crawl through what, in all fairness, may have been the most eventful stretch of the artist’s life, beginning in early 1888, when he left Paris for Arles, and ending midway through 1890 in Saint-Rémy, a few months before his death, at thirty-seven. In between were the milestones that everybody knows a little about: the feud with Gauguin, the ear, the months in the asylum, “The Starry Night.” The show plunders each for relevant information: a cypress grew in the asylum’s garden, there are cypresses in the foreground of “The Starry Night,” and so on. Excerpts from his letters, in which van Gogh burbles over the trees’ beauty and wonders why “no one has yet done them as I see them,” darken the walls. In the exhibition catalogue, we’re told that cypresses were symbols of both the South of France and the Orient, death and immortality, in much the same way that they reminded van Gogh of bright, hot flames and dark, cool bottles.

Halfway through this show, I realized that I had no idea what cypresses meant to van Gogh. Tellingly, this happened when his cypresses were getting especially good. Prior to this—during his first year or so in Arles—they’re more like scene-stealers than leads, and sometimes they’re almost extras. (For “Field with Poppies,” completed in June, 1889, he added some in the background after the rest of the painting had dried.) “The Public Garden,” from 1888, is most interesting as a mark of how much deeper its artist was about to plunge. Two plump, symmetrical cypresses—closer to bottles, definitely, than flames—float in place near the painting’s center, looking like someone ran a comb through them for picture day. Their prettiness is a kind of mask; they’re so neat that they must be hiding something.

The following May, van Gogh checked himself into the Saint-Rémy asylum, where, after weeks of confinement, doctors allowed him to explore the countryside. Something clicked that summer. He started painting cypresses the way that Rembrandt, an early hero, painted flesh, always finding room for one more color, so that what looked green at first would turn out to be a stew of green, blue, and brown, garnished with yellow and red. His brushstrokes do everything but vibrate; thickets of squiggles suggest branches in the wind, echoing the surrounding clouds and wheat fields. Look closely at “The Starry Night” (and it’s a virtue of this show that you can, cleansed of pop-culture preconceptions) and you start to understand how misleading the title is. Singling out the stars almost belittles the painting’s real achievement: the stately arabesques of the trees—closer to flames now than bottles—melt into the curves of the hills and the sky, every part of the picture nudging your gaze onward. The more van Gogh blesses cypresses with their own distinct beauty, the more he makes them look like everything else.

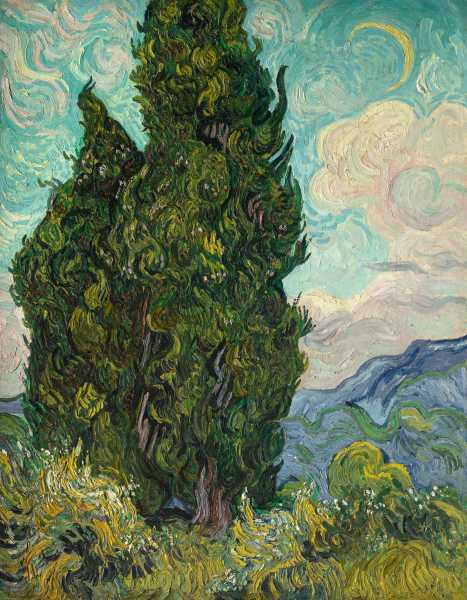

And the “Starry Night” cypresses aren’t even his best. There are times, in these images, when he seems to be testing the hypothesis that an infinite number of curves and colors can be woven into a finite amount of space, until the pigments bulge out of the frame like the Himalayas on a globe. In the painting “Cypresses,” the trees take up half of the canvas, and every non-tree part—clouds, a field, the moon—seems to emanate from their depths. The moon barely shines next to the cypresses’ hard yellow glitter, and the pink of the clouds is only a shadow of the reddish dots in the branches. At a distance, bright pigments meld with neighboring greens and browns to form something dark and solid, almost black in places—van Gogh gives you cypresses at their liveliest and deathliest, so that death itself starts to seem like surplus life. If pressed to explain why I prefer this painting to his most famous one, I’d put it like this: it’s something to make trees seem at one with the cosmos, but it’s something else to make them an actual cosmos.

“Cypresses,” June, 1889.Art work by Vincent van Gogh / Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

If this exhibition is a failure, it’s an absolute banger of a failure, in which the difficulty of cramming van Gogh into a clever little box makes him seem even more colossal than he already did. Early on, the monkish loggings of his cypress fixation start to feel like no explanation at all. That’s fine; lots of artists don’t know why they paint things, and museums aren’t required to solve the mystery. But, then, neither must they argue that van Gogh’s cypresses were “a beacon of hope, perseverance, and resilience,” a statement that sounds, first of all, like something you’d say with a shiny award in hand, and, second, a lot like the Dallas Museum of Art’s gloss on his olive trees: “a symbol of peace, resilience, and renewal.” There’s also the pesky fact that van Gogh didn’t paint many cypresses in the last months of his life, and when he did he often demoted them to supporting roles. The wall text in this portion of the show insists, valiantly, on his “abiding—if unspoken” interest.

It’s hard to study one of van Gogh’s motifs without misrepresenting him. He wasn’t really obsessed with cypresses or irises or sunflowers; he was obsessed with the world and burned through it, one object at a time. He kept painting and drawing. The world kept fluttering away. In one of his letters, written during his first weeks at the Saint-Rémy asylum, he sounds almost like a quantum physicist—“Yesterday I drew a very large moth. . . . To paint it would have meant killing it, which was a pity with such a beautiful creature.” Call it the uncertainty principle of art: there are things whose beauty and vitality the painter can never convey. Nature refuses to hold still, and style keeps getting in the way.

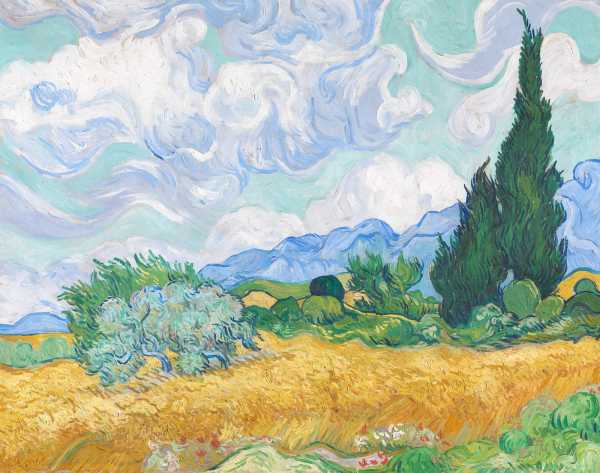

“A Wheatfield, with Cypresses,” September, 1889.Art work by Vincent van Gogh / Courtesy The National Gallery, London; Photograph © The National Gallery, London

This brings us back to that crucial phrase: If you exaggerate the essential, is it still essential? Part of van Gogh’s appeal is that his virtues don’t quite go together—the artist with a dazzling, self-justifying style thought of himself as a dutiful observer of reality. That’s why his art never seems indulgent; he respects the everyday too much to condescend to it. The catch is that you can’t always trust what he says about his work. Consider his two riffs on the same scene: “Wheat Field with Cypresses,” from June, 1889, and “A Wheatfield, with Cypresses,” from September of that year. The earlier painting is choppier, weirder, rougher, completed in the chaos of the open air. Van Gogh preferred the flatter, defanged version that he finished in his studio; he called it the “tableau définitif.” Any fool can see that he was wrong, but he probably needed to be; he needed to care about the definitive deeply enough to keep aiming for it, and to keep falling short in spectacular ways.

You can sense, in some of these cypresses, his effort to get it all down, where “it” means not just the trees but the wind, the fields, the world, and, maybe most of all, the effort. I have no way of confirming whether he captured the essential—I’ve never seen a Provence cypress, and, if I ever do, I’ll be too reminded of van Gogh’s paintings to judge. What I do know is that he succeeded, in the most literal way, at capturing nature: the Met’s team recently discovered bits of limestone and “vegetal matter” in the foreground of “Cypresses.” A simple accident? Sabotage? Poetic justice? Art lovers, start your engines. A century and a half on, we’re getting nowhere with van Gogh, and it’s a glorious place to be. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com