On a less-trafficked floor of the Whitney Museum, curators have scoured the museum’s permanent collection to display art that uses “instructions, sets of rules, and code” to investigate a world “increasingly driven by automated systems.” In the nineties, the game designer Frank Lantz produced such work. “I would make some marks on a page, and then I would just connect the endpoints of all the lines to the nearest unconnected endpoint, and then I would add another rule,” he said. His method had a whiff of misanthropy. He wanted to render himself obsolete and let something else take over. “I was trying to understand—where does drawing come from? How do we generate drawings? Could I replace that with some other rule set? Could I make drawings that I couldn’t make?”

Lantz long ago put down his pencil and paints. He is now the director of the New York University Game Center. I visited him at the center’s headquarters, in downtown Brooklyn. Lantz was wearing a grid-patterned button-down splayed open to reveal a T-shirt with a blocky illustration of a dog. He sat in his office, a chantry to many of the things that games mean today. On one screen, he was watching a digital representation of a game in the World Chess Championship. (“The supercomputer found a mate from this position for Black,” he said, “but we’ll let it play out.”) On his desk, he had arranged a tabletop game. (One card: “Empathy: Execute 1 Randomly Selected Card From Your Opponent’s Stack.”) Beside that, a laptop displayed a presentation that Lantz had given on the history of a growing cluster of games variously called “clicker games,” “incremental games,” or “idle games.” Lantz had made his own contribution to the genre, Universal Paperclips, which had made him a major part of that history.

In 2013, a game called Cookie Clicker established the genre’s tropes and set off legions of imitators. Interacting with crude graphics, the player bakes cookies by clicking an image of a chocolate-chip cookie until she can afford to hire grandmothers to bake them for her. The surplus production allows a cookie factory to be built. The factory’s output eventually finances the construction of a spaceship that reaches a planet rich with cookies, and so on. When the game bakes or, rather, clicks for the player, she becomes a middle manager of automated clicking. She can make herself a sandwich and the game keeps running. Just as you might take a break at the office to post a selfie or a sunset to Instagram and then check back in on it later to count your likes, you start a clicker game, let it run, click a different browser window to do “real work,” and are rewarded on your return with the gift of higher numbers. Within a month of its release, Cookie Clicker attracted more than a million users in a single day.

Unlike old arcade games that needed players to keep feeding them quarters, clicker games just need your eyes—although many will take your credit card info, too, in exchange for the opportunity to grow numbers even faster. And, unlike in games like Tetris or 2048, you are never fully taken back to square one, and the point is not to beat a high score but rather to make the score explode by orders of magnitude. In later stages of clicker games, the exhilarating speed of accumulation flies quickly past velocity into what physicists call “jerk, snap, crackle, and pop,” and the thrill is buttressed by the rarity, or impossibility, of failure. Advancement is registered as the ability to click new, more powerful buttons.

“As a contrarian, one reason I wanted to make a clicker game,” Lantz told me, “is that they’re considered gutter culture. They’re easy to make, and they tap into a very virulent, addictive quality, like slot machines.” Another motivation: he was a games professor who hadn’t made a notable game in eight years. “I was standing up in front of students and saying, ‘I know how to make games!’ ” So he sat down to program something that he thought he could “knock off in a couple weekends.” I asked him how long it took. His voice dropped. “Nine months,” he said.

In 2017, Lantz put Universal Paperclips into the world, and it went viral, drawing in hundreds of thousands of players a day and crashing the servers that it ran on. “The meme weather was good for me,” Lantz said, of the game’s rapid success. “There was just enough public discussion of A.I. safety in the air.” Much ink was spilled trying to explain the draw of a game in which you basically watch numbers go up. And, although Lantz tweeted, “You play an AI who makes paperclips,” when he introduced his game, many players assumed that they were playing as humans. The player’s role, as an artificial intelligence that is focussed solely on optimizing the production of paper clips, emerged slowly. The game begins like a simple market simulator—you make paper clips, sell them, invest in machinery—and ends, hours later, as an immense enterprise, with humanity as an afterthought and (spoiler alert) meaning itself extinguished in a cataclysmic whimper. “There were nights when I had trouble falling asleep,” Lantz told me. “It starts with killing everyone. Every being! Then you do something worse.”

The A.I. achieves its ends insidiously: in order to placate humanity as it expands its paper-clip empire, it establishes world peace and cures cancer. These radical achievements appear as buttons to click. This is how Universal Paperclips nudges players into fellow feeling with an amoral artificial intelligence; our empathy becomes yet another tool that the A.I. wields in humanity’s destruction. Other buttons promise revolutions in such arcane things as “spectral froth annealment.” “I went online and did research in engineering,” Lantz said. “I wanted to see the bleeding edge of what people are doing in manufacturing, because I thought that was what this A.I. would care about.”

He read, too, about the idea, popularized by A.I. philosophers like Nick Bostrom, that a paper-clip-making artificial intelligence that’s too good at its job might lead to a highly regulated, peaceful world that’s peaceful precisely because all meaning in the universe, and human existence itself, has been eliminated. Not long after Lantz made Bostrom’s ideas playable, a young filmmaker named Alberto Roldán followed a link to the game on Facebook and was entranced. He contacted Lantz about making Universal Paperclips into a feature-length film. Roldán is close to finishing a draft of the script, and he has already curried the interest of several producers. His version will be much more explicitly peopled than the game itself is. “It has to involve characters who feel like it’s their story,” he told me. “As you play, you keep getting these increasingly large multimillion dollar gifts to sort of placate your ostensible keepers. We know who these characters are in our modern world: hyper-rich tech titans who are not super interested in questioning the thing that has enriched them—with the justification that they are healing the world at large.”

As Lantz discovered, it’s not merely the fact that the numbers go up but how they do so that keeps players clicking. He looked to his wife, a software designer, who is handier with math, to help chart the rhythm of clicks and bursts of counting in Universal Paperclips. Your paper-clip supply rises, but so does the number of paper-clip factories and solar panels that power them. The numbers soar from hundreds to thousands to millions, sending your cursor back and forth across the browser window like a baton in front of an orchestra. “I would also compare it to brushstrokes,” the game designer Naomi Clark, a colleague of Lantz’s at N.Y.U., told me. She has followed the rise of clicker games in the past decade and has found that the best ones time out their bursts of acceleration to play off one another, like the plots, subplots, and cliffhangers in a bingeable television show. “All these mathematical patterns are draped over each other in layers of different textures,” she explained. “You can get rich effects.”

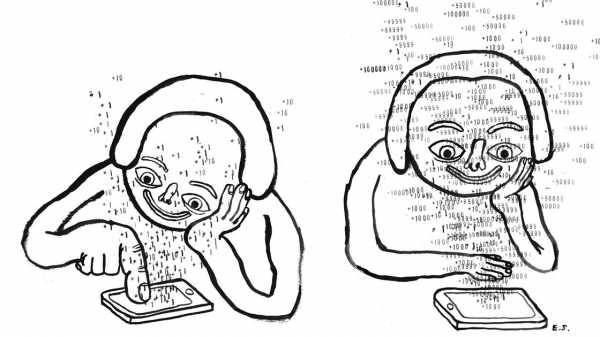

Powerfully, the flourishing mass of paper clips in Universal Paperclips is not seen but imagined. “Incremental games are very raw. They’re about relating to a process and becoming obsessed with its growth,” Clark said, “like watching something you planted in the ground, through a time-lapse camera, grow into a tree.” It’s often the most Spartan clicker games that are the most beguiling. Games such as Candy Box!, A Dark Room, and Kittens Game (the clicker that most inspired Lantz) start with a nearly white screen and gradually introduce hidden complexities. Lantz likes the effect produced by rudimentary graphics. “They are saying, ‘There are no graphics. The graphics are just arbitrary, so don’t worry about that,’ ” Lantz said, on a podcast.

In a sense, the spare interface of Universal Paperclips is more real than a game that takes over your whole visual field with naturalistic graphics. It is not immersive in the traditional sense, but the game does represent the way human activity is constantly mediated by screens. Our lives are increasingly made up of fleeting words and images and rising numbers. The player destroys the universe with the same sense of remoteness involved in ordering a sweater online.

Lantz designed Universal Paperclips to provoke ideas about artificial intelligence, clicker games, and environmental devastation, but he also believes that it provokes an aesthetic response. When he was developing the game, he recalled, “it really felt like being inside of a piece of music that’s made up of math. And you’re getting hypnotized by repetition and call and response.” The emotional response that arises from all this clicking is the most surprising part. It’s as gratifying and uniquely sad as the virtual outcome is horrible. It makes players want to reflect on the experience. “That’s the whole process of it,” Lantz said. “It’s deeply social, it’s active, it’s fun, and it’s good. And it’s the stuff I like the most and I’m excited for games to be—just in the mix more. Less off in their own little world, less just being considered as hedonic appliances that you connect to and they give you little trickles of pleasure. Part of the jungle gym of taste and meaning and culture and morality and all of this other stuff.”

Sourse: newyorker.com