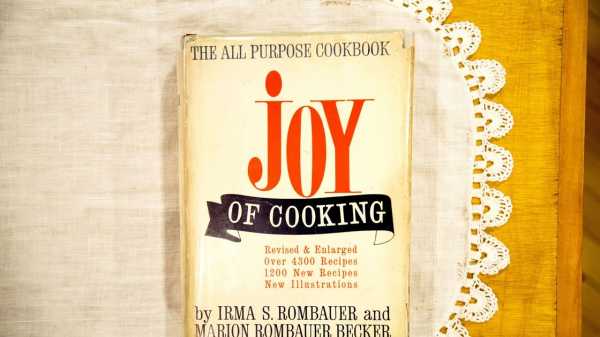

The very first edition of “The Joy of Cooking” was self-published by the

St. Louis hostess and housewife Irma Rombauer, in the first years of the

Great Depression. A relatively modest volume, it collected some four

hundred and fifty recipes gathered from family and friends, garlanded

throughout with chatty headnotes and digressions regarding the finer

points of entertaining, nutrition, menu planning, and provisioning.

Since that original edition, the book has become one of the best-selling

cookbooks of all time. It also has undergone eight significant

revisions: Rombauer’s list of recipes exploded into the thousands;

entire chapters were added (frozen desserts) and dropped (wartime

rationing). (“The” was dropped from the title in the mid-sixties.)

The 1997 edition was a particular departure, replete with contributions

from superstar chefs and celebrity food writers. “Joy” purists considered it something of a heresy (the Times memorably called it “the

New Coke of cookbooks”), and were relieved when the 2006 edition returned to classic

form.

Short of that hiccup, “Joy” has been subject to very little

criticism in its eighty-seven-year life. Smart, bossy, funny, a little bit cornball, the book has been a staple book in

countless American kitchens, a go-to gift for newlyweds and recent

grads, its adherents spreading the gospel to their own children. (When

my parents’ ragged copy of the 1964 edition succumbed to water damage a

few years ago, my mother delivered the news as if a relative had died.)

About the worst that’s been said of the book is that it’s more useful as

a general-reference volume than as a recipe go-to, which—given the

cooking world’s overabundance of recipes and its shortage of genuinely

useful reference books—is actually sort of a compliment.

So it came as a shock, in 2009, when the prestigious scholarly journal Annals of Internal

Medicine published a study under the headline “The Joy of Cooking Too Much.”

The study’s lead author, Brian Wansink, who runs Cornell University’s

Food and Brand Lab, had made his reputation with a series of splashy

studies on eating behavior—in 2005, for instance, his famous “Bottomless

Bowls” study concluded that people will eat soup indefinitely if their

supply is constantly replenished. For “The Joy of Cooking Too Much,”

Wansink and his frequent collaborator, the New Mexico State University

professor Collin R. Payne, examined the cookbook’s recipes in multiple

“Joy” editions, beginning with the 1936 version, and determined that

their calorie counts increased over time by an average of forty-four

per cent. “Classic recipes need to be downsized to counteract growing

waistlines,” they concluded. In an interview with the L.A. Times, Wansink

said that he’d decided to analyze “Joy” because he was looking for

culprits in the obesity epidemic beyond fast food and other unhealthy

restaurant cooking. “That raised the thought in my mind: Is that really

the source of things? . . . What has happened in what we’ve been doing

in our own homes over the years?”

John Becker, the great-grandson of Irma Rombauer, lives with his wife,

Megan Scott, in Portland, Oregon, and they are the current keepers of

the “Joy” legacy. When the results of Wansink’s research were released,

they and their publishers were blindsided. With the help of Rombauer’s biographer, they posted a

response on the “Joy” Web site criticizing some of Wansink’s methods and

calling attention to his sample size—out of the approximately forty-five

hundred recipes that appear in later editions, he’d chosen eighteen, a

mere 0.004 per cent of the book’s content. But they stopped short of

rejecting Wansink’s conclusions outright. “Joy” had always been an

idiosyncratic operation, written and rewritten, over the years, by

strong personalities who held forceful and often conflicting opinions.

(Becker’s grandmother, Marion Rombauer Becker, and father, Ethan Becker,

were each eventually added as co-authors.) “We assumed that he was

probably correct, and that the recipes probably had increased in

calories per serving,” Scott told me recently by phone. “If we had

wanted to impugn the reputation of a sitting Cornell department head, I

think we would’ve found a really tough row to hoe.”

But the study turned up again and again over the years, becoming part of

the conventional wisdom on obesity—a “stand-in,” as Becker puts it, for

the “Sad American Diet.” A cartoon that was commissioned by Cornell’s Food and

Brand Lab and published with the original study depicts a beefy newer edition

of the book haranguing an older edition, jeering at its brother, “I have

44% more calories per serving than you do!” Wansink’s tiny sample set,

especially, gnawed at the couple. In his study report, Wansink explained

the size as a methodological necessity, writing that “since the first

edition in 1936, only 18 recipes have been continuously published in

each subsequent edition.” But, in researching the cookbook’s ninth

edition (scheduled for 2019), Becker and Scott had created an

encyclopedic catalogue of thousands of legacy “Joy” recipes, and they

counted several hundred recipes that had remained comparable from one

edition to the next. When, in 2015, Wansink’s cartoon landed in Becker’s

in-box yet again, he decided to conduct his own research. Becker started

his analysis cautiously, hoping to find a few counterexamples in “Joy of

Cooking” with which to push back against Wansink’s findings. Instead, he

told me, “I was, like, ‘Oh, my God, there’s a lot more.’ I mean, the

numbers are turning up in our favor, and they’re definitely not

determining what Wansink’s got.”

Then, last month, the BuzzFeed reporter Stephanie Lee published a

sweeping exposé of Wansink’s research. Academic standards call for

researchers to articulate a hypothesis ahead of time, and then to

conduct an experiment that produces data that will either prove or

disprove the hypothesis. Lee’s article—which was based on interviews with

Cornell Food and Brand Lab employees, and also private e-mails from within the lab, which were obtained through a public-records request—showed

that Wansink regularly urged his staff to work the other way around: to

manipulate sets of data in order to find patterns (a practice known as

“p-hacking”) and then reverse-engineer hypotheses based on those

conclusions. “Think of all the different ways you can cut the data,” he

wrote to a researcher, in an e-mail from 2013; for other studies, he

pressed his staff to “squeeze blood from this stone.” One of Wansink’s

lab assistants told Lee, in regard to data from a weight-loss study she

had been assigned to analyze, “He was trying to make the paper say

something that wasn’t true.”

Lee’s report wasn’t the first time that doubt had been cast on Wansink’s

work: in 2016, he published a blog post (which he later deleted)

revealing that he had encouraged graduate students to do this sort of

data fishing; the post resulted in a flurry of critical coverage toward

his methods. But Lee’s was the most comprehensive and damning account.

“Year after year,” she concluded, “Wansink and his collaborators at the

Cornell Food and Brand Lab have turned shoddy data into

headline-friendly eating lessons that they could feed to the masses.”

Two days after Lee’s story was published, John Becker posted on the

official “Joy of Cooking” Twitter account, “We have the dubious honor of

being a victim of @BrianWansink and Collin R. Payne’s early work.”

Around the same time, Becker sent his own vast archive of material

related to Wansink’s study—including a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet

tracking the calorie count of hundreds of “Joy” recipes over time—to

several academics, including to James Heathers, a behavioral scientist

at Northeastern University. Heathers is one of a platoon of

swashbuckling statisticians who devote time outside of their regular

work to re-analyzing too-good-to-be-true studies published by

media-friendly researchers—and loudly calling public attention to any

inaccuracies they find. Heathers’s own work—particularly his development

of a modelling tool called S.P.R.I.T.E., which allows likely data sets to be

reconstructed from published results—has led directly to the amendment

or retraction of a dozen academic papers in the past few years, including

several authored by Wansink.

Brian Wansink, who runs the Food and Brand Lab at Cornell University.

Photograph by Ben Stechschulte / Redux

Heathers told me that the problems he’s found in Wansink’s studies are

generally within the numbers themselves: faulty arithmetic, sloppy

recording, subsets of data that disappear at times and then “magically

reappear” later, and conclusions that reverse-engineer improbable

samples. (Working backward from the results of a study about

vegetable-eating habits in children, Heathers

determined that Wansink’s conclusion was only valid if one child had devoured sixty

carrots at once. Wansink published a lengthy correction, clarifying that

the experiment was conducted with “matchstick carrots.” He later

retracted the study altogether.) The methodological flaws Heathers found

in “The Joy of Cooking Too Much” are of a different sort: because the

recipes in question are fixed information, the actual data—ingredients,

quantities, nutritional information—aren’t subject to manipulation.

Instead, Heathers found issues with the study itself. “The problem is

not that it was added up wrong,” he said of the data. “It’s that there’s

no real way to add it up right.”

The recipes were compared on the basis of serving size, for instance,

but ten of the eighteen recipes that were studied do not specify what

counts as a serving. (“Joy” ’s chocolate-cake recipe yields simply “1

cake.”) The small sample size was especially problematic, Heathers

explained, because the calorie changes in the eighteen recipes that were studied varied

drastically, from a hundred and thirty-four per cent increase in the

goulash to a thirty per cent decrease in the rice pudding. “That’s not a

reliable pattern!” Heathers said. Wansink also insisted on only

comparing recipes that bore identical names in different “Joy” editions,

regardless of the accompanying recipes, which sometimes led him to

compare two entirely different dishes. He liked to point to gumbo as one

of the most egregious calorie gainers, but the recipe from 1936, a clear

soup of chicken and sliced vegetables simmered in water, has almost

nothing in common with the sausage-studded, roux-thickened chicken

variety featured in the 2006 book. “It’s like comparing a Chateaubriand

to a whole roast steer,” Heathers said, “and saying they’re both roast

beef.”

When I reached Wansink this week by phone, in his office at Cornell, he

told me that he stands by the analysis in “The Joy of Cooking Too Much.”

“This is a really nice methodology that’s set out,” he said of the

study. But he acknowledged that his team had faced challenges, saying,

“You’ve got to be very careful that the recipes are comparable, and that

the sample frame is one that can be acceptable to a journal, and be seen

as fair.” When I suggested that Becker and Heathers found fault with his

study on those very grounds, he said that the published data was an

abbreviated version of a paper that was “really, really, really quite

long,” and that ultimately had, at the request of the journal’s

editors, several key elements removed, though he couldn’t recall what

those elements were. (He had no comment on the findings of Lee’s

BuzzFeed report.)

Studying what and how people eat is a particularly messy science, in

large part because it’s extremely difficult to control human behavior:

in 2016, the British epidemiologist Ben Goldacre, discussing obstacles

to his ideal experiment,

noted, of its hypothetical subjects, “I would have to imprison them all,

because there’s no way I would be able to force 500 people to eat fruits

and vegetables for a life.” Even factors we assume to be absolute can

fluctuate; the calorie content of a particular ingredient can change

depending on the preparation method, and even on how well it’s chewed.

The result is an academic literature full of often contradictory

advice—Eating animal fats causes massive weight gain, avoid it! Eating

animal fats is the only way to lose weight and keep it off, add it to

your morning coffee!—that can amplify consumer anxiety toward how and

what to eat.

One point that remains consistent, across virtually every nutrition and

health recommendation, is that eating home-cooked meals prepared with

fresh ingredients correlates with better health. This fact is something

that Irma Rombauer seemed to understand instinctively. In an edition of

“Joy of Cooking” from the early sixties, she and Marion Becker advised

that “well-grown minimally processed foods are usually our best sources

for complete nourishment.” With uncanny foresight, on the book’s very

first page, they also issued readers a warning: “The sensational press

releases which follow the discovery of fascinating fresh bits and pieces

about human nutrition confuse the layman,” they wrote. “And the

oversimplified and frequently ill-founded dicta of food faddists can

lure us into downright harm.”

Sourse: newyorker.com