Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

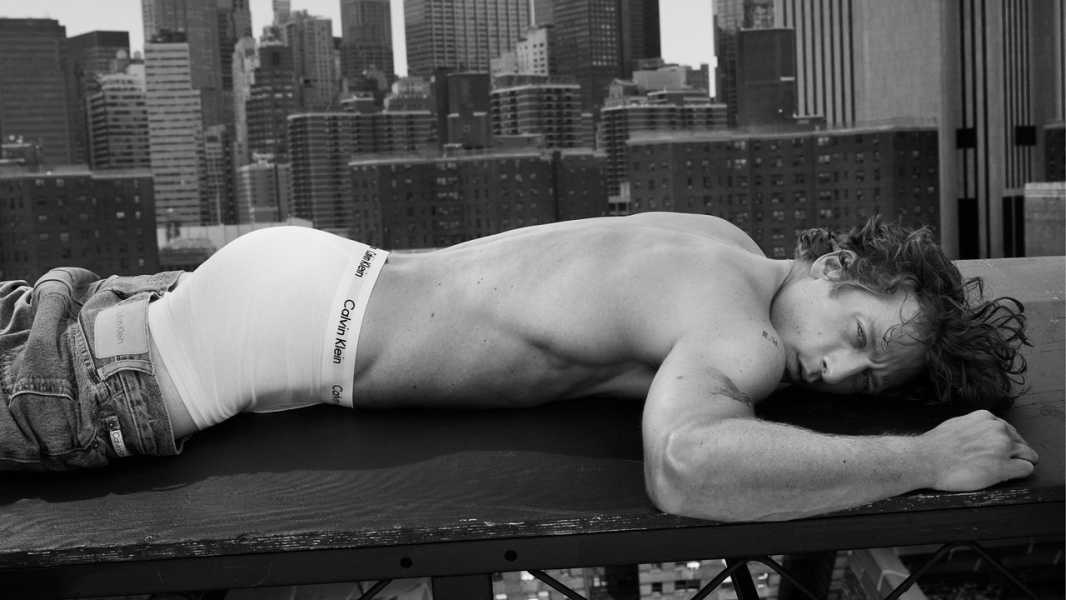

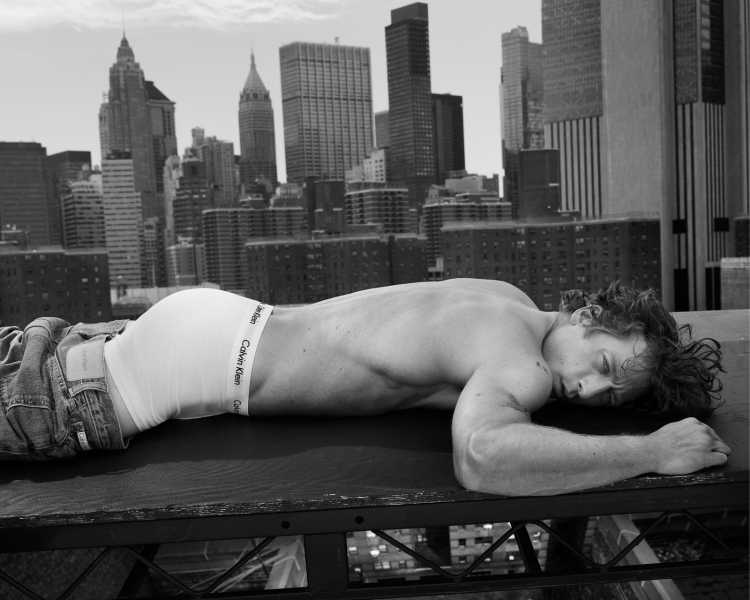

On January 4th, a TikTok user with the handle @aaliyarae uploaded a video of three friends on an erotic pilgrimage to the corner of Crosby and Houston. Earlier that day, Calvin Klein had erected two billboards in lower Manhattan featuring the star of its Spring 2024 campaign, Jeremy Allen White, modelling the brand’s signature boxer briefs. Fresh off training to portray the wrestler Kerry Von Erich in “The Iron Claw,” the actor looks like he is sculpted out of pheromones. The response the campaign received was hormonal. In @aaliyarae’s nine-second clip, which has been viewed more than 3.8 million times, one of the women does an air kiss in the direction of the billboard on the west corner, in which White’s chiselled physique is horizontally trisected, as if he were too much to take in all at once. Later in the video, her friend drops to the ground, bowing in reverence to the billboard on the right that has him lying prone on a rooftop, his shapely backside butting into the Manhattan skyline. The clip’s onscreen text reads “a national landmark.”

White emerged as a sex symbol at a time when his country needed him. The thirty-two-year-old actor is best known for his role as Carmen (Carmy) Berzatto, a young chef who has left his job at a high-end New York restaurant to take over his family’s Italian-beef sandwich shop, on the FX series “The Bear.” The show is paced to match the stresses of a real-life kitchen. The dishes are not prepared so much as they are triaged. Instead of food porn, we are served chaste scenes of monastic focus and devotion. But that was O.K.; for quite a few vocal viewers, the real meal has been White himself. “The Bear” premièred in the summer of 2022, and Carmy, interpreted by White with the precision of a knife, channelled the repressed urges and thwarted carnality of the pandemic years. With his tattooed, grungy intensity, he was the snack the people were craving after two years of slathering on hand sanitizer and stockpiling Clorox wipes. (As one fan put it to MEL Magazine, “This is a dude who will eat you out in a porta-potty at Warped Tour.”)

White’s appeal and Carmy’s are hard to disentangle, and not just because they share a pair of biceps. Each is a god walking among men. Carmy is a prodigy, named Food & Wine’s Best New Chef at the age of twenty-one, but you can find him any day in the kitchen of an ordinary sandwich shop in Chicago. In a similar tone, White has said that he still takes the subway, or rides a fixed-gear bike, when he’s in New York. The Calvin Klein campaign plays into this accessibility kink. To accompany the billboards, the company released a fifty-second commercial, directed by the photographer Mert Alas, that begins with White marching through lower Manhattan wearing a white tank, black jogging shorts, high-top sneakers, and a gold chain. The shirt and jogging shorts don’t stay on for very long, but the ensemble feels of a piece with the aesthetic he’s known for both on and off camera—call it fuccboi minimalism. The commercial then cuts to White jogging up the staircase of a building before making his way to the roof, where he strips down to his skivvies, ostensibly the real star, and uses the metallic infrastructure of the rooftop as a makeshift gym. (As White explained in a 2022 video with GQ, his preferred gyms are the free bare-bones ones New Yorkers are used to seeing in public parks: “I’ll bring some jump rope, and I’ll do some pullups, pushups, dips, all that stuff.”) The ad, scored to Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me,” reinforces the image of White as the people’s heartthrob, one you could conceivably catch around town, jumping rope at the park, selling underwear but not himself.

We’ve had a lot of Calvin Klein beefcake ads in recent years—Justin Bieber, Jacob Elordi, and Michael B. Jordan have all dropped trou for the brand. But, to find an analogue to the public displays of arousal inspired by White’s ad, you’d have to return to the heyday of the label’s underwear campaigns in the nineteen-eighties and early nineties, which reached its apex with Marky Mark modelling the newly invented “boxer briefs” hybrid, in 1992. The company made male models in bulging briefs such a mainstay of urban advertising that a New Yorker cover paid homage to it.

Calvin Klein débuted its first underwear ad in 1982, with the Brazilian-born pole vaulter and Olympian Tom Hintnaus. Shot by Bruce Weber on location in Santorini, the image shows Hintnaus’s tanned body pressed up against the stone backdrops typical of the Greek island, white to match his tighty-whities. His pose, the gender-studies scholar David Coad noted, in his book “The Metrosexual: Gender, Sexuality, and Sport,” was “reminiscent of Greek statuary from the Archaic Period”; namely, kouroi—“large sculptures of naked male bodies which served as devotional offerings to the gods.” The ad evoked the fetish objects of eighties gay-male subculture, including tight, white cotton briefs, and elevated them, literally; the billboard appeared in Times Square measuring forty by fifty feet. Calvin Klein also rented out space in bus-stop shelters across New York City to display posters of the ad. Over and over, the glass was shattered and the posters stolen.

The ad reinforces the image of White as the people’s heartthrob, one you could catch around town, jumping rope at the park, selling underwear but not himself.

Size aside, Hintnaus’s images were bigger than themselves. The ad’s celebration of the male sex object reflected the increasing visibility of gay culture: what had been tucked away inside the adult-movie theatres of Times Square was now in public and on a pedestal. White’s Calvin Klein ad and the ingredients that make up his stardom are a time stamp of our own historical moment, a period of foiled pleasures and desires left on simmer. “The Bear” came out when the restaurant industry, after two years of lockdown policies, was on the verge of cratering. (In Season 2, Carmy’s chef de cuisine, Sydney, played by Ayo Edebiri, reads articles about real-life restaurant closures in Chicago and scrolls Google Maps for the locations of celebrated eateries, like Bridgeport Restaurant and Kroll’s South Loop, only to see the words “Permanently Closed.”) The industry occupied a healthy portion of our conversations during COVID. This was the case not only because restaurants were hard hit but also because they served as a theatre for our competing impulses between self-preservation and community. Dining out was one of the only pandemic-era social activities that there was really no way to do safely. “The Bear” dramatized a culture we had been deprived of for years—one in which the experience of being in public with others, satisfying your appetites in commune, is treated as sacred. No wonder its star has become an object of collective lust.

Since the show’s première, public life in New York has mostly resumed, but the shared spaces of the city are shrinking or disappearing. The wealthy among us seem to be hooked on social distancing, with the Times reporting a different kind of post-pandemic spike: in members-only “clubstaurants,” such as Casa Cipriani. In November, Eric Adams, whose frequent haunt, the exclusive Zero Bond, is not far from White’s billboards, announced dramatic cuts to funding for public services, including libraries, schools, and parks.

With so much behind closed doors, the grand public display of White feels like one of the few delights to be had in NoHo that’s free and for all to indulge in. The day the billboard was unveiled, a friend texted me to say that she was going to stop by on her way from work to see the actor’s flesh in the flesh. “8-foot dick. Every girl’s fantasy,” she joked. I tagged along, for journalism. When my friend and I arrived, we had company. An N.Y.U. student named Hannah had seen it on TikTok and decided to check it out. “I’m a lesbian, but I walked here for this,” she said, smiling. A young woman named Cara was there, FaceTiming with her friend in California. They had each seen the billboard online, she told me, but they wanted to experience it together. Meals are meant to be shared. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com