The photographer Ave Pildas arrived in Los Angeles in 1971, not a high point for Hollywood glamour. Smog choked the city, the Hollywood sign was crumbling, and the old movie palaces had become porno theatres. But Pildas was entranced by the Hollywood Walk of Fame, where he would run errands and eat lunch while working at Capitol Records, as an artistic director. “I was looking around and saying, ‘My goodness, this is like Times Square West!’ ” Pildas said recently. “It was just full of life. There were a lot of actors going to auditions. Most people were wearing shorts and sandals, and, if you saw somebody in a costume, that looked strange. And then, at that time, there were all these hookers in short shorts, and a few massage parlors on the boulevard.”

Pildas was born in Cincinnati in 1939, and got into photography as a “failed musician,” he recalled. His mother forced him to learn violin, and in high school he played trumpet. In college, he started hanging out at jazz clubs in the Midwest, but, short on musical talent, he began taking pictures, which got him a job stringing for the jazz-and-blues magazine DownBeat. He did graphic-design work for the likes of Westinghouse and U.S. Steel, then went to grad school in Switzerland. He was teaching at the Philadelphia College of Art when a former student helped him get the gig at Capitol Records. The job lasted six months, but his fascination with the demimonde on Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street persisted.

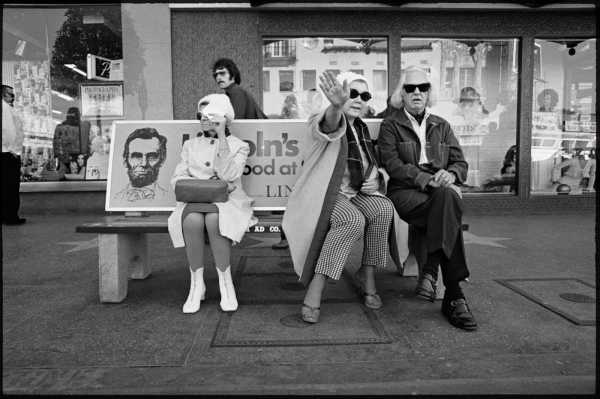

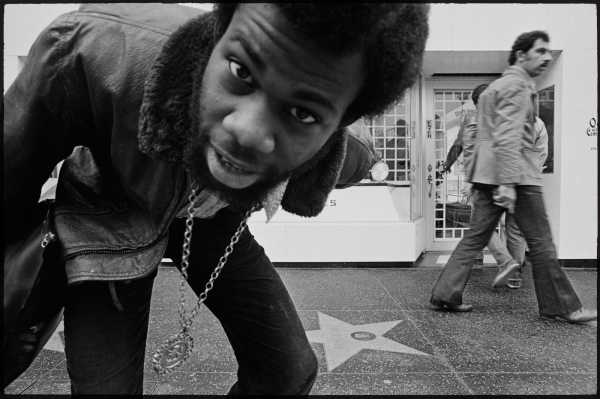

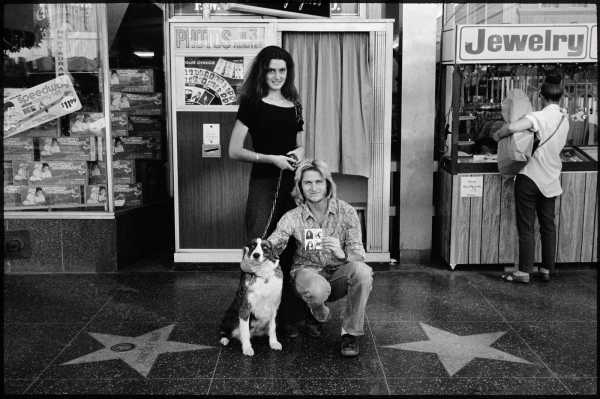

“I would go a few times a week, especially if it was an overcast day,” he recalled. “I wasn’t into shadows at that point in time.” What interested him were the people: tourists and drifters and junkies and aspiring starlets. He would set up his camera on a tripod in front of storefronts or cinemas and wait to see who strolled by. “I would start chatting them up, way before they got to the camera, either remarking about their clothes or their dog. ‘Are you going to an interview or something?’ I was friendly. Then, when they got closer, I would ask them, ‘Oh, would you mind posing for a photograph?’ ” Most people said yes—Hollywood was a place to be seen, after all.

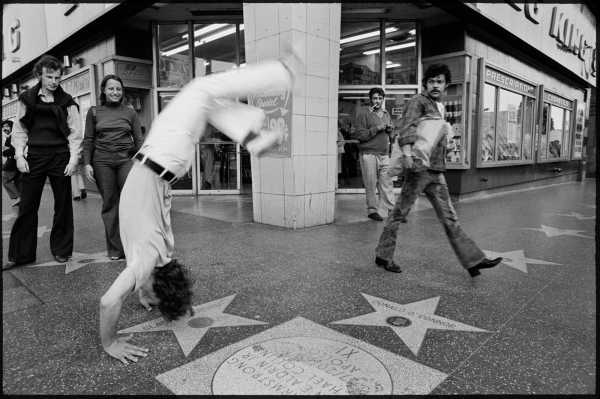

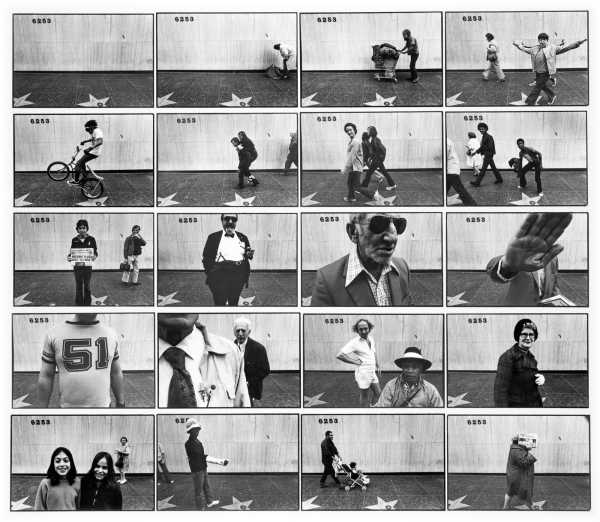

The results, taken between 1972 and 1975 and collected in the recent book “Star Struck,” from Deadbeat Club Press, capture an enticingly seedy sliver of Hollywood history. In Pildas’s portraits, fame is inverted: the gilded names on the stars lining the Walk of Fame (Judy Garland, Marion Davies) are barely visible, while the anonymous passersby get center stage to flaunt their fabulousness. Halloween revelers, old ladies waiting for the bus, cross-dressers, a girl holding balloons—all get a momentary brush with stardom. Even the mannequin heads in the shop windows seem to have attitude. Traces of faded movie magic—like the grand entrance to an old theatre—rub up against the funky, exhibitionist grit of seventies street life. “People come to Los Angeles to be discovered, whether they have talent or not,” Pildas said. For his subjects, he was the discoverer.

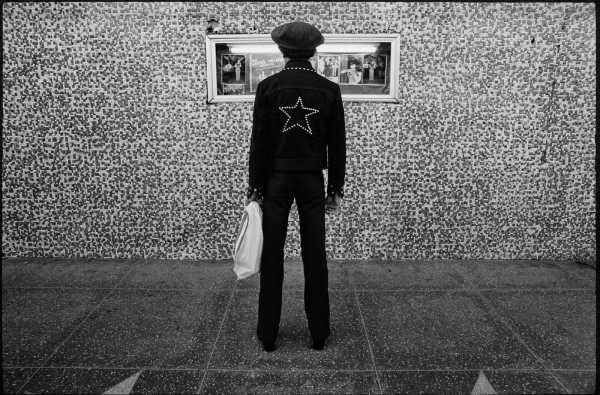

Pildas framed his photos like stage sets. A See’s Candies shop had a gridlike window facing the sidewalk, where a guy wearing a gold chain peered in close to the camera. A Greek restaurant had an interesting spackled wall, with a tiny window hawking belly-dancing shows. “When people stopped to look in the window, I would ask them if I could take their picture,” he recalled. “Then sometimes I would wait for something else to happen, so the picture wasn’t so lonely.” In one, a pair of kid bicyclers take the foreground, ogling the lens through goggles, while an oblivious gentleman in the background reads a newspaper, like a movie extra.

At the time, Pildas was living in the Hollywood Hills, behind the Whiskey a Go Go. On a trip to Europe, he put a hundred or so prints in his backpack and wound up at the Paris headquarters of Zoom magazine. “The French love photography, and they also like Hollywood,” he said. “So the art directors there, they just went crazy over those pictures, and they ran eight or ten pages.” Soon, other magazines picked them up. Then, Pildas recalled, “I put the pictures to sleep. I just put them in my cave, where all of my negatives are, and forgot about them for almost forty years.” He moved to Silver Lake, then to Santa Monica, and took up other photographic interests: Pride marches, silhouettes, a homeless encampment. (His career is covered in a forthcoming documentary, “Ave’s America.”)

Decades later, the Walk of Fame photos started getting traction again. “Besides the pictures, people were interested in the nostalgia,” Pildas said. A friend connected him to Clint Woodside, the founder of Deadbeat Club, an independent publisher and coffee roaster in L.A. “At first, I hated the name, because I was used to Harper & Row or Crown,” Pildas recalled. “I said, ‘Oh, my God, Deadbeat Club?’ And then I saw what he was doing and the care that he put into publishing books.” Revisiting the photos from the distance of half a century, Pildas found some more interesting than he had when they were taken; the little girl holding balloons in front of a record store had struck him as too cute at the time, but it now speaks to a lost era of free-roaming seventies childhood.

Pildas still goes to the Walk of Fame to take photos, especially on Halloween night. “It’s always good for me to go there to jump-start taking pictures, if I haven’t been out for a while,” he said. In some ways, the scene hasn’t changed: there are still fame-seekers and exhibitionists, still tourists searching for stardust. But, in other ways, it’s unrecognizable. There are more homeless people (a microcosm of a statewide crisis), plus people in superhero costumes charging tourists for photo ops. Head shops are in; massage parlors are out. Perhaps most profoundly, our relationship with cameras has changed. “People aren’t as open as they were, for two reasons,” Pildas lamented. “One is that they take their own pictures in selfies, and the other is that they think they’re going to wind up on social media in a bad light. There have been so many rights taken away from people, or they feel that that’s the case, that they are holding onto their right to privacy. So they don’t want you to take their picture, because you’re ‘invading their space.’ I get that a lot now.” But he isn’t daunted. “If people say no, I just go on to the next person, because there’s always something else that’s happening.”

Sourse: newyorker.com