Erotic art by Duncan Grant is on display at Charleston, in East Sussex.Art work by Duncan Grant / Courtesy The Charleston Trust © The Estate of Duncan Grant

What happens in an artist’s private life? In public, Duncan Grant was a charismatic and influential painter, a member of the Bloomsbury group of artists and intellectuals who flourished in London during and after the World Wars. In private, he was equally charismatic, and involved with a series of male lovers—erotic dalliances that he kept hidden to avoid criminal prosecution. Born in 1885, when Queen Victoria still ruled, Grant was a hearty octogenarian when private acts of homosexuality were largely decriminalized in England, in 1967. By then, he was a man of considerable experience, adept at picking up men at the National Gallery and Hyde Park’s Speakers’ Corner. For decades, Grant, a compulsive sketcher, kept hundreds of explicit drawings—scribbled on the backs of paper scraps and grocery lists—out of the public eye. Playful and inventive, they were fuelled by memories of his trysts and his freewheeling imagination. “I can’t speak for anyone else,” he said, in 1970, “but I had relations with anyone who would have me.”

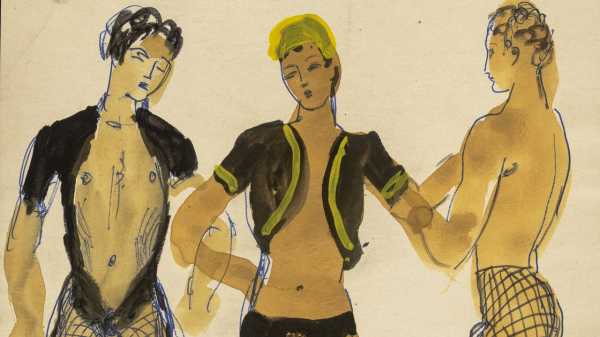

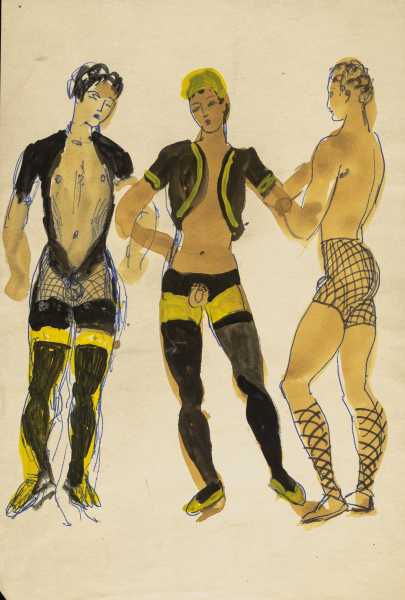

A selection of dozens of the artist’s erotic drawings—from a collection of more than four hundred—has finally been made available to the public, in a joint exhibition at Charleston, the home that Grant shared with the painter Vanessa Bell, titled “Very Private?” and “Linder: A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking.” (The second exhibition refers to work made by the artist Linder Sterling in response to the history of Charleston and Grant.) It is not a shy show. Grant’s drawings are populated by angelic blonds, satyrs, and lanky, muscular bodies in athletic positions of every kind. There are tiny sailor shirts, fish-net stockings, revealing swimwear, and many brass buttons. “They’re such strong images, such sexually charged images, but they’re also incredibly sensual,” Darren Clarke, the curator, told me. “There’s no sense of unease, there’s no coercion—everything feels consensual and sort of joyous.” He mentioned the variety of poses—singles, doubles, throuples, and a study for an orgy—and the sense of an artist’s eye at work. “It’s not just, Here’s a drawing of somebody having sex,” he said, “[but] Here’s a composition of two bodies entwined.”

These particular bodies entwined, or bodies in the process of entwining, would have been dangerous to commit to paper at the time when they were made, in the late nineteen-forties and fifties. In the immediate postwar period, British society seemed to clamp down on relationships outside of the status quo. There was a sense “that everybody should be getting back to the home, and having babies, and doing as they’re told,” Clarke told me. “Making these little nuclear families and rebuilding the country that way.” Under the Criminal Law Amendment Act, acts of homosexuality, among other things, were illegal. Men might worry about being arrested for as little as declaring their feelings in a letter, let alone possessing a trove of naughty pictures. “These would have been really dangerous things to have in your possession, especially so many of them,” Clarke said. Scholars had long feared that the work was lost. “It was thought that the drawings were destroyed, in the way that so much queer heritage and evidence is destroyed by family members to protect reputations.”

As it happens, Grant did belong to a loving family, though not a strictly nuclear one. His domestic arrangement with Bell, whose sister was the writer Virginia Woolf, at Charleston, resembled a traditional family setup much of the time. Bell had taken on the rambling farmhouse in East Sussex during the First World War to provide a refuge for her children and for conscientious objectors, including Grant. (The choice was fight or farm.) In the countryside, Grant cared for Bell’s two sons from her marriage with Clive Bell, and fathered Bell’s daughter, Angelica. By most accounts, Bell was in love with Grant, and she tolerated him bringing along his lover David Garnett. Although Grant’s romance with Garnett faded, he remained steadfast in his friendship with Bell. Between the wars, he spent time with other lovers in a flat in London, but he returned to Charleston often, and saw out many of his later years there. “It was an experiment in living, and an experiment in loving,” Clarke said. “There were lots of jealousies and lots of arguments, but they were trying out new formations of what domesticity and family life could be like.”

The drawings in the exhibition benefit from the energy of new love. Grant had recently fallen for a younger man named Paul Roche, whom he met one day in the street at Piccadilly Circus, in 1946. In a small room in Bloomsbury, Roche would dress up and Grant would draw and photograph him. They created a cloistered, idyllic, and, for Grant, highly productive space. The sheer number of drawings suggests that he was constantly inspired: Roche became a muse. Clarke suspects that, in 1959, in the midst of preparations for a retrospective at the Tate Gallery, Grant decided the drawings needed to go. Perhaps he was worried curators would discover them while tromping around his things. He bundled them into a folder and sent them to his friend, the artist Edward Le Bas. He added a note: “These drawings are very private,” he wrote. “Please give them to Edward Le Bas to do what he likes with them.”

What Le Bas did with them was keep them hidden, like a good friend. When he died, he left them to another artist, Eardley Knollys, who did the same. And so the chain continued for some sixty years, with the drawings passing in secret from friend to friend. When Knollys died, in 1991, the collection went to his longtime friend Mattei Radev. When Radev, a fashionable picture-framer, passed away, in 2009, he left them to his partner, the theatre designer Norman Coates. Coates is where the chain ends. Recently, I met him at his apartment in Fitzrovia, where the walls are covered with paintings that he has inherited from friends—mostly gay men who had no children to pass their collections on to. “I miss all those people,” Coates told me. “There’s a curtain now drawn over that whole world.”

For a long time, Coates kept the Grant drawings in a folder under his bed. He would bring them out to show friends occasionally, but he didn’t display them. “Oh, no way!” he said. “I mean, if my mother were alive and she came, I’d take them down.” When he did show them to people, they were often startled. “I’d say, ‘Don’t try this at home. These positions—you’re going to break your back,’ ” he said. Coates never knew Grant—he was younger than most of that set—but he felt the weight of caring for the drawings. Shortly after Radev died, Clarke asked Coates if he could see the collection, and they looked over the works together. But Coates wasn’t yet sure what to do with them. The timing didn’t feel right for them to be made public. Some people still felt, Clarke told me, “that they were not a key part of Duncan Grant’s work, his œuvre.” “There was a sense that it cheapened his work rather than celebrated it,” he said, of the collection. “That, because it was queer and because it was exotic, it was something to be kept hidden.”

Years passed, and the drawings remained under Coates’s bed. He had already picked out a friend to give them to in the case of his death when, during the pandemic, Charleston contacted him again. The museum was going through a revival of sorts, embracing parts of the Bloomsbury group that had previously remained in the dark. They felt that the time was right to show the drawings. Coates remembered thinking, “Well, actually, yes, the times have changed. . . . People are used to seeing things that they’re quite nervous of.” In 2020, he donated the collection of more than four hundred drawings to Charleston. He kept one—of a man with an erection riding a horse—that hangs in his bedroom. He still worried about the men who had looked after them previously: What would they think? “I became quite anxious about them being shown,” he said. “But I’m pretty convinced it was the right thing to do.”

At Charleston, the show, which runs until mid-March, hangs in a gallery adjacent to the farmhouse, behind a sign that reads “These exhibitions include depictions of explicit sex acts.” Clarke met me at the entrance. Inside, the drawings are striking not only for their subject matter but for their ephemerality. They don’t have official names, or dates, and they are framed simply, in black. A portrait of a nude man with his arms behind his head was drawn on paper ripped from a spiral notebook. Some of the positions are rendered in what looks like ballpoint pen. “I think he must have been doing them just of an evening, listening to the radio,” Clarke said.

Traces of Grant’s public work run through the drawings in unexpected ways, like fragments of waking life in a dream. One non-explicit sketch, for a commission to illustrate “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” shares space with two men pleasuring each other. In his public life, Grant made several paintings based on a troupe of Chinese acrobats who visited London. In the exhibition, the acrobats appear again, in more intimate compositions. In the nineteen-fifties, Grant designed the costumes for an opera, “Venus and Adonis,” and sexualized versions of the outfits appear in the drawings. Clarke pointed out one with three men in Roman sandals, fish-nets, and black-and-yellow stockings. “You could probably wear that to a fetish club,” he said.

Mixed in among Grant’s work are responses from contemporary artists, including the photographer Ajamu X, whose images of nude Black men dominate a wall. Many of Grant’s lovers and models were Black, and the couples in his drawings are often interracial. Ajamu X reimagines these compositions without white men—the results are arresting, a tangle of sculpted bodies. The photographer Tim Walker took inspiration from a drawing hat tGrant made on the back of a grocery list—bread and eggs, oranges and cornflakes—for a series of photos piled on top of one another. In the images, the explicit and the domestic mingle: there’s an oversized box of cereal, a discarded slice of bread, and a sex act in full flow. Seen alongside Grant’s illustrations, the effect is dizzying, and a little overwhelming: so many contortions, so much skin.

In a quieter room off of the main gallery space, there are portraits of the men who kept the drawings hidden through the decades. Le Bas and Knollys are at an easel; Radev, painted by Grant, stares ahead intently. They were taking a chance, too. Earlier, I had asked Coates what he thought Grant would have made of the show if he were alive today: his private life finally made public. “I think he would have been quietly amused,” he said. “And probably also think, Well, what’s the fuss?” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com