It’s an iconic photo, easily found on Web sites devoted to the First World War, first sent out to newspapers in 1917, with the caption, “Funeral of the first American soldier killed in battle in France.” In a cemetery in the small village of Sommerviller, a French chaplain reads the funeral service as a dozen soldiers stand at attention, eyes trained on the casket poised above the grave, a mound of fresh earth beside it. The sky is gray; a barren wood lines the horizon. One could mark the start of what’s come to be called the American Century here—it is possible to look back and trace a line from that moment straight to the United States’ dominance in world politics at mid-century and beyond.

I look at the photo and see something else: my grandfather Joe Marshall, standing on the right, the second man in the front row, as he put it in a letter home to his parents. Joe is wearing a doughboy helmet and, he points out in the letter, “what looks to be a fur collar” but is actually the khaki sweater my grandmother, Elizabeth Metcalf Marshall, his bride of six months, knitted for his twenty-eighth birthday, just a few weeks before. My grandfather had not planned to be in the photograph; his face is turned away from the camera. But, as the deputy press officer in charge of photography and film for the American Expeditionary Forces, he’d set up the shot and, later, from his office in Paris, posted the image around the globe.

I knew none of this until, as the centennial of the Armistice that ended the First World War approached, I decided to look through several boxes of family letters and photographs to learn what I could of my grandparents’ war experience. My grandfather was a retired life-insurance salesman in his seventies when I knew him best—if I knew him at all. He was tall and thin; in memory, a blur of gray hair, gray wool cardigans, and trousers. When I was growing up, in Southern California, in the nineteen-sixties, we would have family dinners with my grandparents, who lived one town over, on Sundays and holidays. My grandfather maintained a nearly mute formality, speaking more words in French, sotto voce, with my grandmother, than in English. My grandparents had lived in Paris through the war. Their first child, my uncle Joe, Jr., had been born there. That much I knew.

There were hints of an adventurous life before the war. The small mahogany yo-yo, for instance, which I was allowed to play with after dinner, and which my father said was the first yo-yo to reach America, brought back by my grandfather from the Philippines, in 1915. My father told me, too, about a poem that his father recited to his children every night at bedtime. “Day by day I float my paper boats, one by one down the running stream,” it went. “In big black letters I write my name on them, and the name of the village where I live. / I hope that someone in some strange land will find them and know who I am.” It was written by the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1913. My grandfather had met him, my father said, at Tagore’s ashram, outside Calcutta.

These few facts didn’t square with the silent elderly gentleman at the head of the dinner table, forgotten by everyone but my grandmother, who coaxed his appetite with real butter for his white bread and mint jelly for his slice of lamb. And, in some ways, the letters I read, half a century later, only deepened that mystery. But they also brought to life the man in the photograph, and reminded me how much we lose when we turn away from the past.

Joe Marshall in his Harvard College dorm room, Hollis 31, during his senior year, 1912-13.

Photograph Courtesy the Papers of Joe Truesdell Marshall /Accession 17926 / Harvard University Archives

The funeral that my grandfather witnessed at the front was not, in fact, the first American burial in the war. It was the ninth. There had been no members of the press on hand for the first one. It was not Joe’s first glimpse of the war: he had lived in wartime Paris, for six months, two years before, mastering French in preparation, he hoped, for a diplomatic career. In those months, he’d come to recognize “the look of the trenches” in the eyes of soldiers returning from the front, many of them grievously maimed, and he knew of the protracted, deadly stalemates that characterized most of the war’s battles, months-long contests that moved the front lines a few kilometres at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives.

But that day in Sommerviller was Joe’s first sight of the war up close. He and the journalists whom he ferried by limousine from Paris had come to photograph American soldiers in the trenches, and to interview survivors of the German raid. Dropped off outside the village, Joe and his press corps trailed an American Expeditionary Forces sergeant across a muddy field that ran between the two lines of fire; enemy shells landed on the crest of the hill toward which they were climbing, then, mercifully, as the men approached, shifted to targets behind them, “plunking down in the field from which we had come” and making “a nasty noise,” as he wrote in a letter home. “You hear the report of the cannon; then a ripping tearing sound, sometimes a thud, then the explosion.” At each “crack” of a German battery, he explained, with impressive understatement, “there is a moment of very real interest as you listen for the whine of the shell” to discover its direction.

Joe and his crew reached safety in “a perfect labyrinth” of trenches, and were given canes to keep from slipping on the round sticks that served as flooring in the mud. An officer guided them to the “calm sector,” where the first American troops to reach the front had been moved into position in late October, and where the raid had taken place under cover of darkness. The German encampment was a mere five hundred yards away, across no man’s land. Joe peered cautiously over the edge of the trench, glimpsing a tangle of barbed wire at the bottom of a steep incline and the ridge of German trenches beyond. He imagined the confusion and terror that must have gripped the Americans, still unfamiliar with the layout of the trenches and expecting at least a modicum of calm. A medical officer told of finding one of the dead, Thomas Enright, “with his throat cut and every evidence of having put up a desperate struggle.” Shreds of German uniform were strewn about, and the ground was scuffed up. The doctor had pocketed the lethal weapon, “straight-bladed” like a paring knife, and showed Joe its wooden handle with two indentations—notches, the doctor supposed, registering the number of men killed with it.

But Joe had come to “make some pictures.” The shadowy trenches proved troublesome to photograph, and word of an American burial in progress suggested a better opportunity. Four American soldiers bore the coffin, followed by a French honor guard, then American and French officers, and, last, an American firing squad. A bugler blew taps, the squad fired three volleys, and the coffin was lowered in what was, Joe wrote to his parents, “a touching ceremony for all of us.” He walked to the end of the cemetery, where the first three American graves were now protected by low wooden fences. As he copied down the names—Enright, Hay, Gresham—he rested his notebook on the railing, and found it difficult to keep from flinching as the nearby batteries continued to crack. Six more graves had been dug in line with the first three, and Joe saw “names from many different ethnic backgrounds, all young Americans caught in the war.”

Joe’s interest in world affairs had been sparked four years earlier, when, as a college senior at Harvard, he’d heard Tagore lecture on Indian philosophy. A transfer student from the University of Kansas, Joe spent more hours at his fraternity and with the Glee Club than on his studies—until Tagore’s message, of “the harmony that exists between the individual and the universal,” took hold of him. The Marshall family was moneyed, having parlayed the financial success of a general store in the early days of Kansas settlement into extensive holdings in corn fields, and Joe embarked on a world tour after graduation, stopping for as long as he was welcome in the homes of new friends whom he met sailing first class from San Francisco to Hawaii, Japan, the Philippines, and, finally, India.

Reaching Calcutta at the end of July, 1914, he looked up his former Harvard classmates Jatindra Nath Set and Hira Lal Roy—partisans, he soon learned, in the fledgling Indian independence movement that Tagore was helping to lead. They offered to take him to meet Gurudeb, as the poet was now known to his followers, at his nearby ashram, Santiniketan, “the abode of peace.” When Joe arrived at the collection of low white buildings set around a spreading banyan tree on a broad and vacant plain, he was ushered into Tagore’s presence by the poet’s son-in-law, who must have startled Joe with the declaration that Joe wrote home about later: “Out of the millions of people in America you are the one who has been selected to come and visit us, to bring us their message, and take ours in return. . . . East and West have now met here at Santiniketan and you must not leave until we have time to understand each other.” Over a breakfast of tea, toast, and mangoes with a berobed Tagore, Joe promised to return for a longer stay. The conversation had “a soothing effect,” Joe reported, despite the guru’s dire prediction: “Europe is as the setting sun. It has risen in its greatness and power by unnatural means; and as the sun sinks in a flood of red light, so Europe will sink in a flood of red blood.”

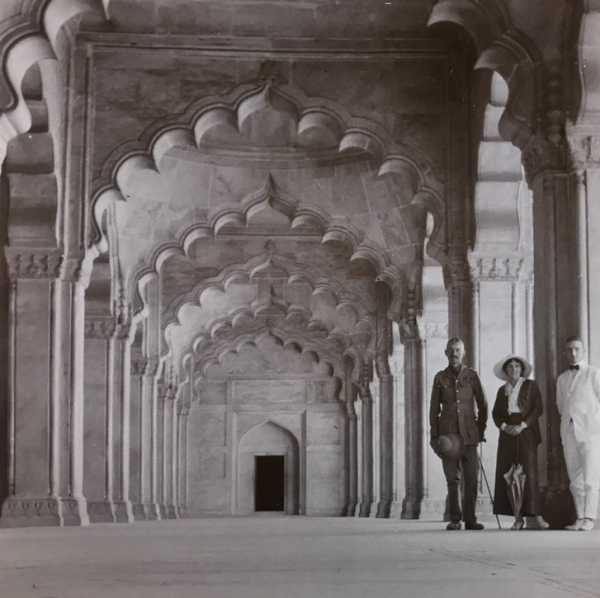

Joe Marshall, in a white suit, in India, 1914.

Photograph Courtesy the Papers of Joe Truesdell Marshall /Accession 17926 / Harvard University Archives

Had Tagore received the news without telling Joe—or were powers of divination at work? When Joe got back to Calcutta, he learned that Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia, and that Germany had declared war on Russia and France. On the day that Joe was meant to return to the ashram, Great Britain declared war on Germany.

Remarkably, Joe did not immediately curtail his world travels. But, stalled in Darjeeling with a case of malaria, his previously vague ambitions began to coalesce: to marry, and to do something to help France and its allies. He would spend a semester in Paris perfecting his French, and he would intensify his correspondence with Elizabeth Metcalf, the slight, rosy-cheeked Wellesley girl from Detroit, whom he’d met in the parlor of his fraternity after a Harvard-Yale game, and whose friends on the sailing and tennis teams called Sunbeam. When he returned to America, in late 1915, he organized a series of concerts in ten Kansas cities—he’d sing “Invictus”—and raised ten thousand dollars for the Kansas Belgian Children’s Relief Fund he had established. And he proposed to Elizabeth. They celebrated their engagement with a gala party in April, 1917, the same month that Congress voted to declare war on Germany.

The couple had planned to settle in Kansas City, but Joe, instead, travelled to Washington, D.C., to work his connections with government men he’d met on his world tour. At the end of May, he telegraphed Elizabeth. His language skills had merited him a commission as a special interpreter to General John J. Pershing; he would soon leave for France. “I love you with all my heart,” he wrote. He was boarding a train to Detroit that night. “Will you marry me Thursday evening?”

On the day of their wedding, Joe learned that he would not be allowed to travel on Pershing’s military transport—there were too many interpreters on board. Joe and Elizabeth enjoyed a brief honeymoon in Washington, still believing they would be separated, until Joe gained permission to sail on a French passenger ship as a civilian. He could bring Elizabeth.

After crossing the Atlantic on La Touraine, a vessel carrying the volunteer ambulance corps of several East Coast colleges, the two settled in a pension on Rue Vaneau, convenient to both A.E.F. headquarters and the Alliance Française. Elizabeth, who’d spent the previous year teaching in a girls’ school so that she could help her family with money, began studying French literature and art. At a time when other American couples who married hastily in the shadow of war were separated by a vast and dangerously mined ocean, Elizabeth could join Joe after work for performances at the Opéra Comique. They could pack their treasured French picnic basket for a Sunday outing at Versailles—where, Elizabeth wrote in her diary, “we didn’t try to go everywhere, secure in the thought that we would go many times.”

Joe’s rise from interpreter to press officer, at the rank of second lieutenant, was rapid. He had toyed with photography at Harvard, and on his world travels, and, somehow, he managed to pick up film-editing skills as well; these were still new technologies that many of his elders could scarcely fathom. By the time Joe went to the front, in November, 1917, he was supervising six hundred men: “operators, developers, censors, stenographers, messengers, etc.” It was a job that “requires vision,” he wrote home, “for there are no precedents to guide me.” He would leave the Army as Captain Marshall.

Joe often credited life with Elizabeth for his success. He pitied his fellow-officers, who would “wander aimlessly about the hotel lobbies smoking innumerable cigarettes, plainly bored and lonesome.” How much better it was to come home for a convivial meal at the pension with his wife, then retire to their fifth-floor room, pull their “big aristocratic armchair” up to the French windows, open them wide, and curl up together, gazing at the sunset and the Eiffel Tower. “In the midst of excitement and stress and sorrow, we two are keeping our heads and living simple normal lives,” Joe wrote.

Joe Marshall with his wife, Elizabeth Metcalf Marshall, and their son Joe, Jr., in Paris, 1919.

Photograph Courtesy the Papers of Joe Truesdell Marshall /Accession 17926 / Harvard University Archives

The Marshall family’s corn fields had been suffering disastrous growing seasons, with too much and then too little rain, and so the couple mostly lived on Joe’s lieutenant’s salary, the first he’d ever earned. Elizabeth, already accustomed to economizing, didn’t mind. “We are just ridiculously in love,” she confided to her mother, and “we never could have stood it apart from each other.” As for the narrow bed the pension provided, she wrote, “here’s a real Marshall secret—we prefer it narrow.”

Without realizing it, Elizabeth had conceived during their May honeymoon, or perhaps on the Atlantic crossing. In August, an American doctor explained her summer-long queasiness by confirming the pregnancy. She continued attending classes at the Alliance Française, which permitted her to tour museums and cathedrals closed to the public in wartime. Her mother was a tireless clubwoman who kept insisting that Elizabeth “do something” for the war effort but, with a baby on the way, Elizabeth felt she was doing plenty. She read the Paris papers daily and summarized the news for Joe; occasionally she aided him in translation work. “I haven’t forgotten that I can be of use,” she assured her mother, but “homes and babies and knowledge—those things have to go on well, too.” In the weeks before the due date, Germany launched a campaign of aerial attacks on Paris with its heavy Gotha bombers. Joe took out an expensive “war risk” life-insurance policy; when, on January 30th, a bomb was dropped straight through the house across from theirs, and then merely “thumped out into the street,” going off like a “fizzer” instead of exploding, the couple joked about Joe’s prescience in saving a monthly premium by setting the policy to start on February 1st. That same night, a bomb landed on the Crédit Lyonnais where Joe received occasional cable transfers from his father. It blew out the corner of the building, killing two.

Two weeks later, on Valentine’s Day, Elizabeth was playing four-hand piano duets with her landlady when labor commenced. At the American hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, Joe was allowed to attend the birth, talking his Sunbeam through what proved to be an easy labor. (The doctor credited Elizabeth’s “athletic life and ability to relax.”) Elizabeth savored a compulsory month-long recuperation at the hospital, but when she and the baby returned to the pension, she couldn’t sleep, and her breast milk stopped flowing—small wonder when blasts from “la grosse Bertha,” a German cannon, interrupted a nighttime feeding, or a fire engine, that “machine of noise and horror,” raced down Rue Vaneau, warning of an air strike, “leaving in its place only a nameless questioning of the sky above us.” Joe, Jr., was losing weight.

In May, Joe and Elizabeth went to Île-aux-Moines, a coastal island in Brittany, where there was a small American colony, fresh sea air, and a milk cow for the baby. Joe could only spend the night but, after one week in a hotel, Elizabeth made up her mind to rent a house and stay for the summer. (“I believe it’s the first time in my life that I ever decided anything for myself,” she wrote to Joe, on May 24th, their first anniversary.) Their families back in Kansas and Michigan begged Joe to send Elizabeth and the baby home, but Joe refused, stressing the value of living through “these tremendous events together.” He doubted if “a thousand years at Detroit or Kansas City could ever have brought us to the same degree of mutual respect and love and understanding that this year in Paris has given us.” And “we haven’t let anything make us sad either,” he claimed. “There is so much sorrow now that it is one’s duty to be gay and happy just to show others that the world hasn’t gone all to pieces after all.”

Still, a note of desperation crept into his defense. “We are in this cursed business to do our full duty,” he wrote. Censorship rules prevented him from explaining his work and the “influence it may have on the war” to his parents, “but Elizabeth knows,” he went on. Elizabeth knew, too, that Joe wasn’t well—he’d also been losing weight. In late June, he checked into a Red Cross hospital in Paris with the Spanish flu. The attending surgeon prescribed a three-week leave, writing in his orders that Captain Marshall “is much debilitated from over-work.” He would spend the time in Brittany.

Joe arrived at Île-aux-Moines believing the war might go on for another two years. As he rested in the shade of a fig tree in the garden behind the seaside cottage that Elizabeth had rented, his infant son napping in a carriage beside him, he considered how all five of his commanding officers had stepped down from exhaustion, nervous breakdowns, or illness, often leaving him in charge. It was not “an easy sort of work.” Three junior officers had been required to fill his place while on leave. Was he succumbing?

Then, while Joe was still in Brittany, a major military counteroffensive from the Allies brought the grinding Second Battle of the Marne to a close. The Germans were finally outmaneuvered by a swarm of Allied tanks at Reims, the cathedral town ninety miles from Paris. When Joe returned to work in August, the mood in the press office had shifted. Paris was safer now. “No one can overestimate the part the Americans played in turning the tide,” Joe wrote home. In September, Elizabeth and the baby returned from Île-aux-Moines to a “cute little house” Joe had rented in Le Vésinet, “the most modern” of the Parisian suburbs. Joe had regained his energy, if not his weight. “Every hour, these days is so filled with the present that there is very little time to look backward,” he wrote home on his twenty-ninth birthday, October 11th.

One month later, Joe jimmied his way through a locked door at the Chambre des Députés and pressed forward into the packed assembly hall to hear Georges Clemenceau, “the grand old man of the war,” announce the terms of the Armistice. The Prime Minister read out all thirty-four paragraphs in a clear, matter-of-fact voice, Joe wrote afterward, “and it made my blood tingle to hear those words.” Each article brought renewed applause until Clemenceau silenced the crowd to issue his own words of gratitude to the “glorious armies” and “render honor to the brave men who had given their lives for freedom and justice and humanity.” Then someone started the “Marseillaise,” and “the whole assembly took it up with a swing that was great.” Joe sang until the tears rolled down his cheeks.

Joe was granted an honorable discharge in January, 1919, and commended as an officer of “attractive personality, well disciplined, and with executive ability.” He might have taken his family home, but he’d rented the house in Le Vésinet until May. “I don’t know of any young couple who will start out in the ‘reconstruction’ period with better preparation,” Joe wrote to his parents, explaining the decision to stay on through the spring. He’d always believed his work in the press office would give him “the most valuable experience for after-life.” He and Elizabeth were “anxious to whirl into the adventure.” Joe planned to spend the few months writing a book on Clemenceau, and he offered himself to the Kansas City Star as a Paris correspondent to report on the peace process. But, before the ink on his letter was dry, he’d received an invitation to serve for six months as “publicity man” for the newly formed League of Red Cross Societies, “about the biggest thing that is happening these surprising days,” he wrote, in a letter home. With a salary three times his Army pay, the job was “the greatest opportunity for service that has ever come my way.”

It would require two weeks of meetings in July, at Geneva, where the League’s permanent headquarters were to be established. Before heading there, Joe took a Sunday off for a final French picnic with Elizabeth, an excursion by train to “the devastated regions” around Reims where the Yanks had proved themselves in battle. The couple packed their basket with sliced veal, sandwiches, strawberries, and a thermos of hot chocolate, and joined a crowd with the same outing in mind at the Gare de l’Est. Just past Château-Thierry, Elizabeth wrote, they began to see the results of war: “Dear little villages nestling at the foot of a hill and surrounded by well-kept green fields,” and yet with church steeples toppled, walls razed, thatched roofs collapsed. She wondered where the farmers lived who cultivated those fields. Nearing Reims they came upon “a vast plain of desolation,” riddled with trenches, blanketed in red poppies. She plucked a blossom to enclose in her letter. As for the city of Reims, “it was so sad and terrible—not a single untouched house . . . nobody, nothing there,” she wrote. Joe and Elizabeth gazed up at the cathedral’s massive walls and buttresses and saw sky.

When Joe returned from Geneva, he had a decision to make. “The choice has come between moving to Geneva for another year or coming home to you,” Elizabeth relayed to their parents. Joe wrote a few days later of the “real opportunity” to make the Red Cross “my ‘life work’ if I were so inclined.”

Stay, I wanted to tell my grandparents, as I read their words—this is the “after-life” you prepared for, not the dreary years spent peddling life-insurance policies to the neighbors in Southern California. But there was more. “Perhaps we have done wrong in always writing you such optimistic letters,” Joe wrote; “we didn’t want you to worry,” he added. Elizabeth supplied the details: Joe was “tired and thin,” perhaps suffering a recurrence of malaria. “Traveling is difficult, food scarce.” Finally: “We want to see you and be with you and start our life in America.”

In August, Joe rallied to join an eight-member Inter-Allied Medical Mission, in Poland, where, Elizabeth wrote, the Red Cross “has been given the tremendous work of handling the typhus epidemic” originating in Eastern Europe. This time Joe took the photographs himself, converting the best of them to glass lantern slides, so that they could be projected at public lectures or in presentations to governmental bodies. He secured a set of fourteen slides of his own—striking scenes of destitute families, refugees in freight cars, a “sad-eyed Polish peasant” whose wife and children had died of typhus as refugees in Russia. “Drugs, hospital supplies, and clothing are urgently needed,” Joe’s captions read. “A very severe epidemic will occur this winter unless the necessary equipment and supplies are received to enable the medical authorities to deal energetically with the situation.” Joe carried the packet of slides with him in October, 1919, when he and Elizabeth sailed home with Joe, Jr., their “Petit Parisien,” on the same French liner on which they’d shipped out. In snapshots, their wide smiles suggest that they were eager to return.

Tenement residents in Poland, photographed by Joe Marshall in 1919, when he was a member of an Inter-Allied Medical Mission organized by the League of Red Cross Societies.

Photograph by Joe Marshall

The first year home, however, brought losses more painful than anything they’d experienced abroad. Joe’s mother succumbed to the tuberculosis she’d suffered from for more than a decade. Elizabeth’s favorite sister died in childbirth, losing her baby. The young son of a beloved cousin died that year, too; when my father, Joe and Elizabeth’s second child, was born, in December, 1920, they gave him the little boy’s name.

When Joe had received the special interpreter commission, he’d written to his parents, “I will know all the inside history of the greatest of all wars.” Did he ever start writing his book on Clemenceau, or another he’d planned about his own wartime experiences? He had made carbon copies of his letters to work from, but I found no outlines or drafts. In 1920, he ran for a seat in the House of Representatives, on the slogan “Send a Soldier to Congress,” but he didn’t win. He had lived through the war from its beginning, in August, 1914, until its end, more than four years later. Most Americans had only a brief experience of the war. It didn’t loom as large for them.

Joe’s disappointment over the election may have inspired the family’s move West. As the Marshall cornfields in Kansas steadily failed, Joe scraped together enough cash to buy two neighboring house lots in Altadena, California. He planned to build and flip houses, as we’d say today. But, after the first bungalow was finished, California’s real-estate crash of the nineteen-twenties rendered the scheme useless. My grandparents sold the next-door lot at a loss and simply stayed.

When Joe and Elizabeth were first in France, in the summer of 1917, Joe had told his parents, in a letter, that, through college and his world travels, he’d often “thought I was in a false position outside of the main channel of life and affairs.” Then the war had come along, he wrote, “the realest piece of business the U.S. ever tackled.” Perhaps he felt the insubstantiality of his position once again when he returned to Kansas, bearing fourteen glass slides picturing a destitute people in a feudal landscape, each one numbered and keyed to a caption with information of no consequence to anyone he knew.

But, the truth is, I don’t know how he felt. I didn’t know my grandfather, and, in the way of our impecunious family, did not even fly home for Joe’s funeral, when he died while I was away at college in New England—no one had considered the price of my plane ticket a worthy expenditure. By then we’d given a name to what had become more than a habit of silence at the dinner table: senility. At Thanksgiving the year before I left for college, he’d gotten up from the table, unnoticed, and disappeared. My grandmother cruised the neighboring streets in her aged Plymouth until she found him pacing the sidewalk, agitated, lost.

What I’d discovered of my grandparents’ lives in their letters was so much more impressive, so much more interesting, than anything I’d imagined. Why had I not heard any of these stories? Why had I not searched for them sooner in the brown cardboard boxes that arrived from California in the late eighties, after they had died? I’d stacked the boxes in an attic closet and left them there while I read the letters of people unrelated to me and wrote up their lives instead. Perhaps Joe could manage only so much self-invention to meet a changing world. Perhaps, as the years passed, disappointment grew to eclipse what was once a matter of pride, or even rendered the early accomplishment a shameful point of comparison. Or perhaps the war and what Joe saw of its effects in France and Poland was so horrendous that “accomplishment” didn’t signify. “Think of the stories we can tell our grandchildren of our experiences in Paris during the great war of 1917,” Joe had written to his parents, defending his decision to bring Elizabeth along with him. But he never did.

Sourse: newyorker.com