In 1973, Paul Allen was a twenty-year-old technologist who, like many celebrated entrepreneurs, had taken a leave of absence from university to pursue work as a programmer. Over plates of pizza one summer day in Vancouver, Washington, he posed a fanciful question to his longtime classmate and soon-to-be business partner, Bill Gates: What if you could read headlines from a personal computer terminal without needing to get your hands on a copy of the day’s paper? “Come on, Paul!” Gates replied. “It costs seventy-five dollars a month to rent a Teletype, and you can get a paper delivered for fifteen cents. How do you compete with that?”

As Allen recounted in his memoir, “Idea Man,” from 2011, the initial mission of his venture with Gates was, if simple, still radical: “A computer on every desk and in every home.” The benefits of personal computing now seem self-evident. They were once nearly unimaginable. At Seattle’s tony Lakeside School, Allen and Gates had learned to code on a communal terminal linked to a remote mainframe much larger than the modern-day refrigerator. As late as 1977, the president of Digital Equipment Corporation, an early giant of the computer age, told members of the World Future Society that there was no reason anyone would want, let alone need, to use such a device at home.

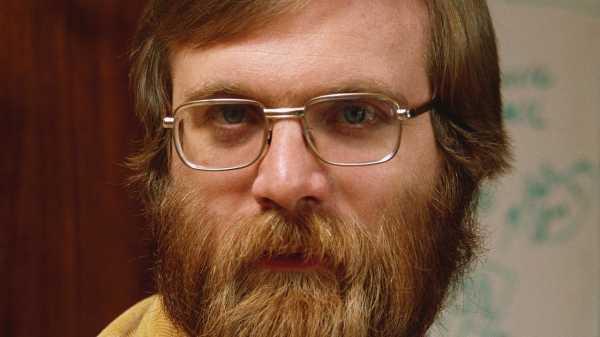

Had innovators like Allen not fought to transform their hobbyist subculture into a mass medium, it is unlikely that you would be reading these words on any screen, let alone your own. “Paul foresaw that computers would change the world,” Gates wrote, earlier this week, of his first business partner, who died on Monday, at the age of sixty-five, from complications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. By the time Allen’s first battle with lymphatic cancer forced him to resign from Microsoft, in the eighties, he had already helped to establish the industry standard for microprocessor languages, beginning a technological revolution that cemented the reputation of the company—where I interned in the summers of 2017 and 2018—as the largest and most profitable software enterprise of the twentieth century. Allen’s technological expertise and prescient leadership are partially responsible for many of today’s most fundamental technological innovations, among them point-and-click computing, word processing, and the multi-button mouse, which Steve Jobs once denounced as a fussy extravagance during a business meeting that the visionaries had arranged in Palo Alto. (“You know, Paul, this is all about simplicity versus complexity,” Jobs told Allen, who recounted the episode in “Idea Man.” “And nobody needs more than one button.”)

Unlike the millennial billionaires who condescend to non-technical pursuits, Allen attributed his entrepreneurial ambition and imagination to a wide-ranging autodidacticism and a natural passion for art and literature. From his father, a librarian, and his mother, a schoolteacher, he inherited a love of reading: in his senior yearbook portrait, Allen’s chin rests atop a stack of tomes that includes “Dubliners,” a college-level physics textbook, a history of the Mexican-American War, and the Bible. “I read every science book I could find,” Allen wrote, “along with bound issues of Popular Mechanics that were hauled home from the university library to be devoured ten or twelve at a gulp.” His inspiration for Microsoft’s inaugural software product—an interpreter of the BASIC programming language—came from a 1975 issue of Popular Electronics, another of the periodicals that Allen consumed in his youth. After reading a story about the Altair 8800, then the most powerful minicomputer ever presented, he rushed to Gates’s Harvard dorm room to pitch the venture that eventually compelled his co-founder to drop out. “That moment marked the end of my college career and the beginning of our new company,” Gates wrote this week. Microsoft was founded in Albuquerque, where the men relocated to build software alongside the Altair’s manufacturers, but the men soon moved the company to their home state of Washington, hoping that Seattle’s rainy days would prevent employees from becoming distracted. (They neglected to consider the city’s sunny, resplendent summers.)

After Allen left Microsoft’s management, in 1983, Seattle remained the primary focus of his life’s philanthropy. In 2000, the chairman of the architecture department at the University of Washington, where Allen later endowed a separate school for computer science and engineering, likened him to a modern Medici. Allen’s intense investment in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood, home to Amazon’s headquarters, has recast the city as an increasingly popular destination for young technologists. But his most cherished contributions to the city’s scene and skyline may be the artistic and athletic monuments to which Allen devoted a notable portion of his wealth. He restored the old Cinerama movie theatre in Bell Town to modern glory and commissioned Frank Gehry to design a pop-culture museum that honors, among other legends, Allen’s idol Jimi Hendrix. He developed a children’s center at the Seattle Public Library, funded an off-campus studio for the beloved public-radio station KEXP, and established a military-history museum outside the city. He emerged, too, as an ardent advocate of environmental protection, computational bioscience, and space exploration, donating millions of dollars to regional nonprofits. An inveterate sports fan, Allen used his wealth to acquire the Seattle Seahawks, a team that had considered leaving the city before he stepped in. “At times, I cast my net too widely,” he wrote in his memoir, responding to criticism that his philanthropy lacked focus. “But my choice of ventures wasn’t arbitrary.”

By the time I arrived at Microsoft, two summers ago, Allen had been absent from the company’s management for decades. But his energetic curiosity lingered in the corporate culture, which welcomed rather than dismissed interests beyond technology—including my own, as both a writer and a programmer. (This past summer, the company made me a job offer.) I was first alerted to Allen’s death on Monday night by a deluge of messages from other former interns lamenting the loss of our forebear. In one of many online forums devoted to his legacy, an anonymous engineer wrote, “Had he not provided the funding, I wouldn’t have had the technology at my high school that inspired me to take the career path I did.” The tech industry is notorious for its relentless, mercenary, and sometimes merciless desire to push forward. Allen, even as a champion of technology, understood that the products he designed were complements to preexisting lives, all of them rich and varied. “That’s a core element of my management philosophy,” he wrote in his memoir. “Find the best people and give them room to operate, as long as they can accept my periodic high-intensity kibitzing.”

Sourse: newyorker.com