American poetry in 2018 is a massive oak, and I’m not going to try to jam it back into its acorn. Words like abundance and variety come to mind, only to be swatted away as inadequate, plus a little patronizing. Mine is one view, helpfully elevated, unhelpfully insulated. The best view of poetry is to have no view, to be lost inside a line, a poem, a book, a new or newly reanimated tradition. That’s where you find the happiest moments. Then you resurface and try to tell the world what kinds of insanely beautiful visions you were shown. You were taken to where the culture’s keys are hidden, then sent somewhere to dry out.

My metaphors strain, which is their nature: it’s how you know they’re metaphors. So, poetry is an oak, unless it’s an ocean. In any case, it’s an environment that you move around in, not some map you impale with little pins. Poems struck me from the white of the page, as they always have, but a newly vibrant and central art of performance, abetted by social media and streaming video, made the page at times seem a crude trot, the Xerox of a Xerox. The immediacy of in-person performance—embodied voice—meant that it was more important than ever that persons, and not merely voices, be somehow represented on the printed page, and respected when we teach, discuss, and read aloud poems.

I will tell a story, so as to give a sense of the state of the art. It is one story of one period of twenty-four hours in poetry.

Here at Wellesley, where I teach, our students recently hosted an open mic with the extraordinary poet and performer Danez Smith. It was a frigid October night, the kind of night that makes living in New England seem like a terrible idea. When word reached the faculty that Smith was going to be visiting, some wondered how such a thing could have happened without our Stewardship and Influence. Even in the very recent past, a poet of Smith’s prominence would have been booked by such-and-such a department, with so-and-so sponsoring, introduced by Eminence No. 1 and feted, following, at a dinner for the important grownups. Frank Bidart and I sat in the audience as some of the students performed, while Smith, sitting with us, live-tweeted out praise and support for their work. You could see how the culture of poetry had flown right over the gates that once constrained it. A new kind of night, I thought, as, later, feet up, I ate my take-out at home and browsed Twitter for reactions.

The next morning, I taught a seminar on Emily Dickinson. Here was an entirely different setting, though some of the same students were present. Dickinson’s manuscripts, which settle so unhappily on the printed page, where their quirks cannot be reproduced, can now be accessed online in bright facsimile: here are the creases of her folded pages, the look of her handwriting as it climbs the right-hand margin or expands or contracts to fill up the empty places on the paper. Envelopes, chocolate wrappers: where does the poem end and the material surface begin?

I thought of Smith, vivid in person, only fractionally less vivid on YouTube, and of Dickinson, her manuscripts freely available online for her readers, so real that you almost feel like you can smell them. Both of these poets had in some sense transcended print, though both can be accommodated by, and enjoyed in, a printed book. I love thinking about how their unique instruments—a microphone, a manuscript—can and cannot, as Robert Frost put it, be “brought to book.” One of the oldest problems in poetry—how to render the hectic presence of the person in the static notation of the written word—has been rebooted for our moment.

Here is my small Best of 2018, intentionally scant and in no order; if I were to expand beyond this list, I would agonize too much about who I excluded. To invert Marianne Moore’s maxim: omissions are accidents.

Jenny Xie’s “Eye Level” presents to us the travelogue of an introvert, its angles and points of view shifting, aspectual, scrambling time and place. The poems are brilliant formal solutions to these sometimes disorienting dispersals. The book sets us down inside a mind both restless, chasing the next insight, and, despite itself, composed. And it’s full of marvellous perceptual ironies: “On the bus ride back, / we pass a store named Ni Hao, / selling pelts. Hello in all directions.”

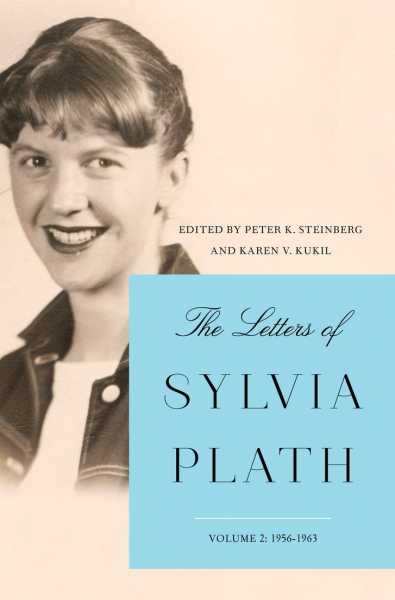

“The Letters of Sylvia Plath, Volume II, 1956-1963,” edited by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kulik. The second volume of letters, meticulously edited, with a lively introduction and a great index, brings Plath’s entrepreneurial resourcefulness, her bared heart, and her prosecutorial intelligence into one book. You can find motifs from her poems in their original contexts—a woodchuck in the forest, the recipes that required her to slice her onions (and, as in “Cut,” her thumb), her old mare, Ariel. The decline into madness is fast and cruel: the volume prints, for the first time, Plath’s distressingly frank letters to her friend and psychiatrist, Dr. Ruth Beuscher.

jos charles, “feeld.” Charles, a medieval scholar, has written a book like none other: in a personalized version of Chaucer’s fourteenth-century English, charles, a transgender woman, renders poems of unusual beauty and lyricism, rather sweet and wide-eyed yet wholly alert to the insufficient embodiment of trans experience in the English canon. This is my current favorite book of 2018.

Forrest Gander’s “Be With” is a book of harrowed elegies for his partner, the poet C. D. Wright, who died suddenly in 2016. The book’s sputtering, flinching style, with its syntactical dead ends and missed connections, feels like both an accommodation to the necessity of language and proof of its inadequacy.

J. Michael Martinez, “Museum of the Americas.” Diorama-like, this book displays what has been, in American culture, displayed, and thereby displaced. It is at once a natural history of American racism and colonialism, utterly devastating in its cumulative impact, and a gorgeous mash-up of genres and forms: bold, light, and ruthlessly smart.

Max Ritvo, “The Final Voicemails,” and Max Ritvo and Sarah Ruhl, “Letters from Max: A Book of Friendship.” Ritvo died, too young and quite famous, in 2016: he was twenty-five. These books suggest that his legacy is secure in others’ hands. “The Final Voicemails” contains Ritvo’s last poems, some of them written when he was certain he would soon die, and a version of his remarkable undergraduate thesis—advised by the editor of this volume, Louise Glück. Ritvo and Ruhl, the American playwright, became close friends; their correspondence, including poems, is a one-of-a-kind document.

Terrance Hayes, “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin.” Hayes wrote seventy sonnets after the election of Donald Trump; this book is, therefore, a kind of diary of its own undertaking, as, once more and then again once more, Hayes finds the unlikely energies and inspirations to write the poems we’re reading. A wild work, effervescent and despondent, Hayes’s collection of sonnets reminds us that the mastery of time is one of poetry’s important functions, though sonnets only buy it back in hasty fourteen-line bursts.

A. E. Stallings, “Like.” Stallings, an American poet living in Athens, Greece, is the foremost formalist poet of our time. She’s found perhaps the most troubling and interesting word in current English use—“like”—and used it as a deep dive into the nature of representation, the current brutal politics of self and other, and the commodification of emotional response.

Joan Murray’s “Drafts, Fragments, and Poems: The Complete Poetry,” edited heroically and brilliantly by Farnoosh Fathi. Murray, who died in 1942, was selected posthumously by W. H. Auden as the Yale Younger Poet, in 1947. She’s been a vital concern of poets and readers ever since, a poet of tragic promise, almost certainly launched on a major career. This book gives her corpus the heft and variety that poets who live much longer lives might envy. Her “abrupt transitions and changes of scene,” wrote John Ashbery, “bring her readers to the brink of an amazing discovery.” That discovery was Murray’s gift itself. She suffered from a congenital heart condition yet loved climbing in the mountains of Vermont and upstate New York: she carried “a reindeer bone handle, my fetish companion,” with a scrap of pelt stuck to its sheath. Murray knew that her pioneering off the page was a method of survival linked to her pioneering on it.

Sourse: newyorker.com