When I took over the editorship of Tatler (the old social flagship of the British upper classes that once had loitered on every coffee table of every stately home in England) in June, 1979, it had declined into a threadbare shiny sheet with staples through it trying to masquerade as an upmarket magazine. The only faintly recognizable collateral from its glory days were the pages at the front of the magazine, which featured host-approved snapshots of posh-looking stockbrokers and their tweedy wives, and choleric colonels and plump-shouldered débutantes grimacing at each other over a glass of warm amontillado or milling with company directors in very new deerstalkers at country-race meets where you might get a whiff of the royals.

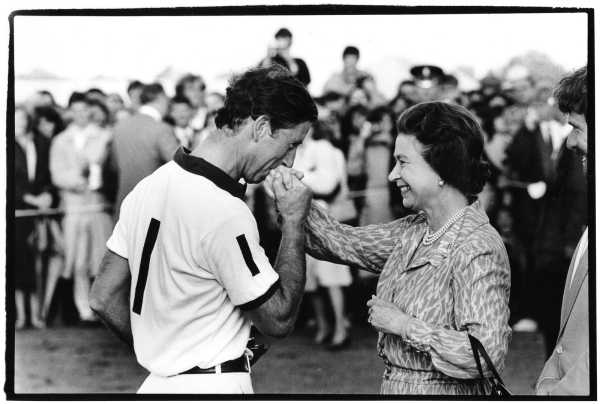

Prince Charles and Queen Elizabeth II at a Guards Polo Club match. Windsor, 1985.

The Tatler photos were the polar opposite of what had begun to make a splash in RITZ, the raffish social newspaper of the late nineteen-seventies that was modelled on Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. Edited by the late David Litchfield, a former filmmaker, RITZ offered a parallel social world of louche café society, specializing in “candids” of such figures as Mick Jagger staring glassily in a flowered hat and eye makeup at one of Lord Glenconner’s Mustique galas, or dissolute closeups of half-eaten haute cuisine littered with cigarette stubs as a dazed Bryan Ferry and Jerry Hall float decadently past in glamorous disarray. I am not sure which of these worlds was more—or less—inviting, but as the new editor of Tatler I knew that they should not be mutually exclusive.

Historically, it was the right moment for the magazine to take a new visual direction. England was on the cusp of Mrs. Thatcher’s ascendance to Downing Street, and with it came an era of social division and hard-charging new money. In the words of Lady Hartwell, the wife of the Daily Telegraph’s editor, at a lunch party in Buckinghamshire, “At last we live in a world where we can sack people again.”

Margaret Thatcher arriving at the Winter Ball. Grosvenor House, London, 1984.

By the early eighties, the ruling class had its confidence back, but there was also—as the harshness of the Thatcher years played out—a nostalgia for the “Brideshead Revisited” era of aristocratic whimsy and frolicky romance. (The BBC TV adaptation of “Brideshead” ruled the airwaves in 1981.) The pages of Tatler needed to reflect all these crosscurrents, the emerging social edge, the high-low social mix, the secret excesses that still existed behind the closed doors of the great houses of England, and it needed to be chronicled with a cleverly irreverent point of view.

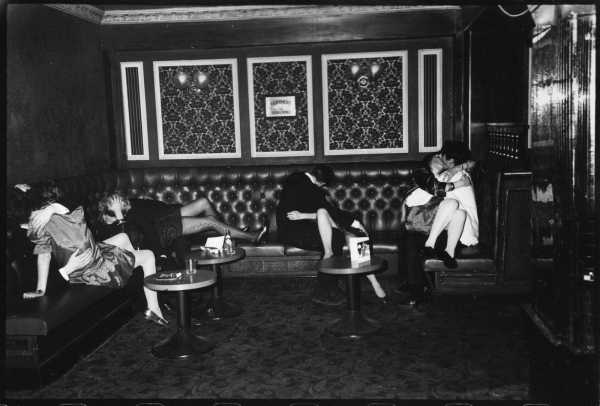

Feathers Ball. Hammersmith Palais, London, 1981.

I knew how to do it in words, with impudent headlines, cover stories, and ironic literary voices, but who to express the editorial vision in pictures? Tatler was still captive to the old guard of social photographers who enjoyed free access to the most top-drawer aristocratic festivities. Two of Tatler’s stable were Barry Swaebe and Desmond O’Neill, courteous buffers of a certain age whose bread was buttered by the people who invited rather than assigned them.

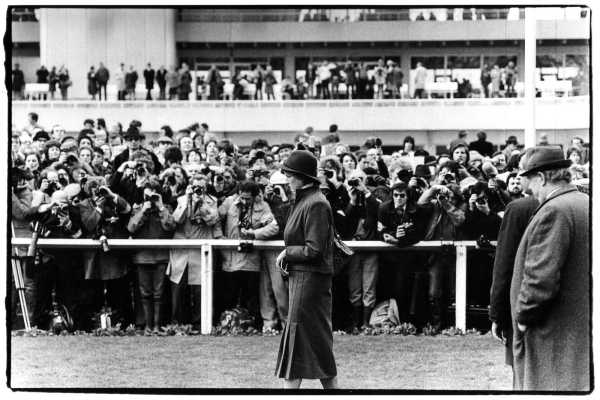

It was in February, 1981, after two years of searching for the right sharp-eyed lens, that I saw a pre-publication edition of a Sunday Times magazine that featured the winners of a photography contest. One of the suggested topics was “The Return of the Bright Young Things.” The series by the runner-up, one Dafydd Jones, immediately caught my eye with its stark black-and-white definition and the sheer effervescent brio of its depiction of oblivious aristocratic bad behavior—photographic moments as memorable as Evelyn Waugh’s sentences. I assigned Dafydd to follow the then Lady Diana Spencer when she attended the race meet at Sandown Park in March, 1981. He shot her in black and white, eyes down, running the gantlet of hungry paparazzi whose lenses were all trained in her direction. We used it as a double-page spread beneath the headline “Di, Di, over Here Di, Di . . .” It became the classic, early image of a hunted future princess.

Lady Diana Spencer at Sandown Park. Esher, 1981.

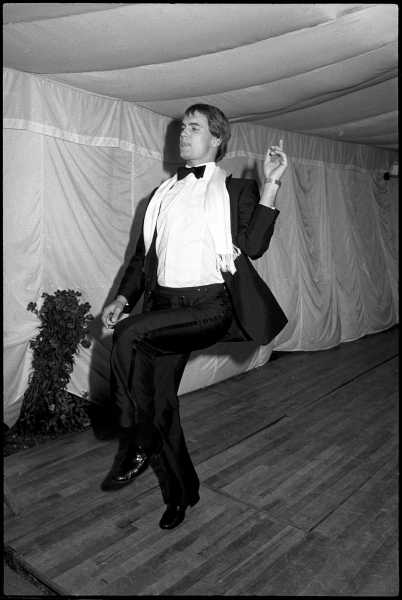

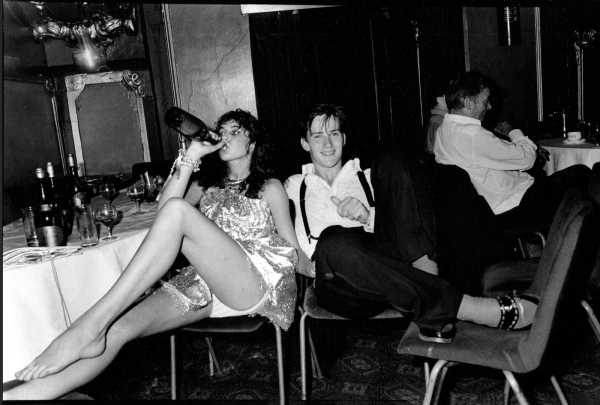

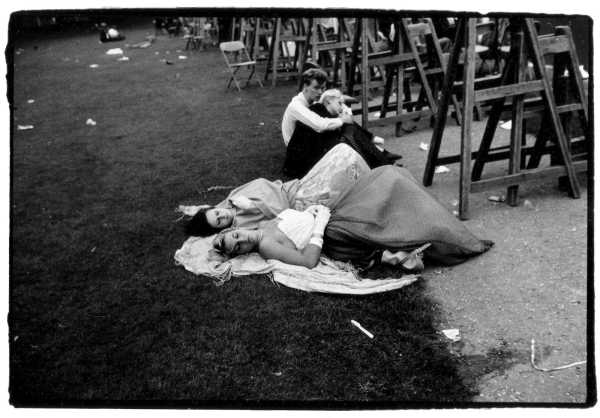

I asked Dafydd to bring his portfolio into Tatler’s old headquarters on Bruton Street, and resolved there and then to make him our party photographer. He was a strikingly elfin presence, so young, so hesitant, so unassuming. His own humble origins, including attending a state-run school in Oxford and making extra money as a campus cleaner, were the perfect townie vantage point from which to view the privileged antics of the Oxford jeunesse dorée. Throughout the next eight years, his pictures became the defining images of the new Tatler, reflecting more pointedly than all our glossy competitors the inimitable look and feel of a strata of society at play. Because he was so understated, he was able to be invisible. Because he always knew what he was looking for, he was usually the last to leave, producing wonderful motifs of sleeping young beauties with their long, lissome legs sprawled on padded banquettes with their entwined dance partners, or lolling with a friend on a summer lawn at the end of the revelry. Unusually for an outsider who penetrates the inner circles, Dafydd was never co-opted by the world he covered. Check out the picture of an unself-conscious youngblood stepping out that is straight out of Monty Python’s “Ministry of Silly Walks.”

Stephen Windsor-Clive at a Temple Muir dance. Wickham Place, Essex, 1981.

Carolyn Wroughton and Shona McKinney at Jo Farrell’s thirtieth birthday party. Polish Club, London, 1988.

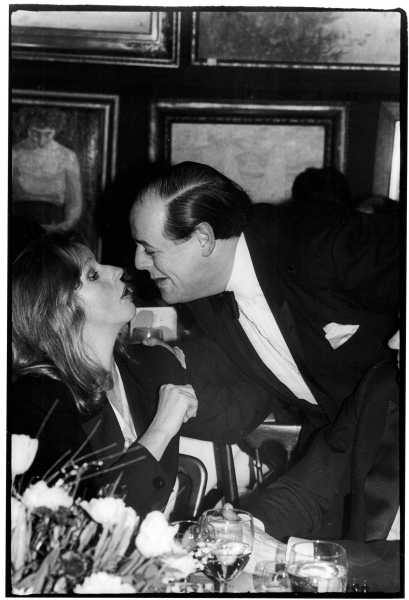

Lady Gowrie and the Rt. Hon. Nicholas Soames, at a Sotheby’s gala auction in aid of the Courtauld Institute of Art Fund. London, 1987.

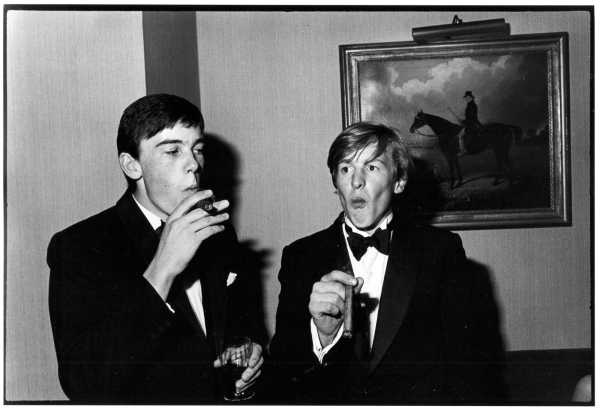

There is no one better than Dafydd at capturing the moments of privileged pretension—such as the two-shot of the posturing, bow-tied, young William Nott and Edward Hoare sucking on their cigars as if they were already haw-haw-haw fifty-year-old members of White’s club. Or charm and smarm in motion, as the grandson of Winston Churchill, the Rt. Hon. Nicholas Soames, with his brilliantined side parting, leans over at a black-tie dinner to kissy-kiss the proffered pout of a winsome blond Lady Gowrie.

William Nott and Edward Hoare at the gentleman’s club Boodle’s. London, 1981.

Annabel Harris and Cosmo Fry at a party at the Lyceum Theatre. London, 1982.

Revellers at the Sandhurst Commissioning Ball. 1988.

Dafydd is probably most famous for his quintessential Hooray Henry photographs of exploding champagne bottles, or the madcap Sebastian Flyte-ness of a group of Young Things sledding down a mountain in St. Moritz on a dining table. A print of the moment when a scissor-legged deb in full formal dress is tossed by a raucous toff into a lily pond at a party now hangs on my sitting-room wall in New York.

Charles Mcdowell pushes Pop Vincent into a lily pond during the Martin Betts Dance. Ascot, 1982.

David Kirke, Tim Hunt, Nicky Slade, and Lord Xan Rufus-Isaacs ride a dining table in the Dangerous Sports Club ski race. St. Moritz, Switzerland, 1983.

Dafydd’s brilliant evocation of a time and a class only seem more potent today, when we know that so many of the moneyed twits in his eighties portfolio ended up running the country, as they always have. His genius is to preserve something elegiac in the satire. These were, after all, just young people having fun.

Early morning at the Trinity May Ball. Cambridge, 1984.

This is drawn from “England: The Last Hurrah.”

Sourse: newyorker.com