Orson Welles was too much for just one career, or for one life, and circumstances reduced him to less of both. A consummate Shakespearean, he never filmed “King Lear,” but he lived it, finding himself to be a king without a throne, prematurely aged. While still in the prime of his vitality, he endured a jolly celebrity that barely sustained him but dragged him ever further from the art that was his raison de vivre. American movie institutions were in collapse in the nineteen-sixties and in rebirth in the seventies and early eighties, and, in fall and rise, they bear the shame of neglecting Welles, whose last studio-backed movie was “Touch of Evil,” from 1958, and whose inspiration almost all film luminaries, veteran or newcomer, depended upon, even more than they’d dare to admit.

Welles’s last dramatic feature, “The Other Side of the Wind”—which was filmed between 1970 and 1976, left largely unedited at the time of his death, in 1985, and only recently completed—turns his camera into a mirror that reflects his own precarious position in the movie industry. It dramatizes Welles’s own struggle to finance it and the thorny web of personal relationships on which its production both depended and foundered. (It’s arriving Friday at the I.F.C. Center and on Netflix.) Incompletion, frustration, desolation—the ruins of grand schemes and grand schemers—were his lifelong themes; they’re at the center of “The Other Side of the Wind,” and they nearly swallowed it up. The film places Welles, in the form of a dramatic surrogate, living up close to the business with his nose pressed against the window, trapped inside his own legend; it depicts a truncated career and an unfinished film, and life itself replicated the movie. “The Other Side of the Wind”is a settling of scores—with Hollywood, with the times, and, above all, with himself. It is a belated work of his colossal artistry, and one of the great last dramatic features by any director.

“The Other Side of the Wind” is also, for better and for worse, uncannily prescient—possessed of passions that were rare at the time of its making but eventually became celebrated, then became commonplaces. It is a mockumentary—a faux documentary about the last day and night in the life of a director, Jake Hannaford (played by John Huston), whose seventieth birthday is being celebrated at a big party thrown by his former star from the prewar era, Zarah Valeska (Lilli Palmer), while he’s in the midst of shooting a large-scale movie without studio backing, which is also called “The Other Side of the Wind.” The making of that fictitious film—which, for clarity’s sake, we’ll call the film-within-a-film—is the heart of the story, and roughly edited footage of it is prominently featured throughout. As for the making of the faux documentary, it brings “The Other Side of the Wind” full circle in Welles’s career: his first feature, “Citizen Kane,” is also about the making of a documentary about a fallen grandee.

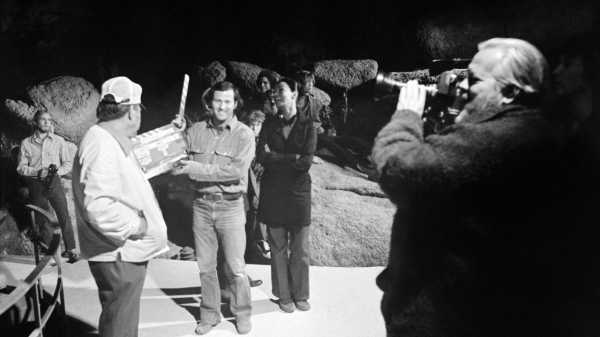

“The Other Side of the Wind” starts with a montage of images from the endgame of Jake, narrated by his friend and associate, the director Brooks Otterlake (played by the director Peter Bogdanovich). The voice-over, set in the present day (at the time of the film’s completion), and delivered by the now-elderly Brooks, at forty-plus years’ remove from the depicted events, explains that the footage in “The Other Side of the Wind” is the ostensible work of the crowd of documenters—journalists, paparazzi, students, critics, scholars, film-school emulators—who fill the ranks of the party-goers while recording Jake’s every move and his surroundings for their own purposes. (Most of Welles’s films feature scenes of the reckless jubilation of unhinged revelry and end with the rueful desolation of the endless morning after. In “The Other Side of the Wind,” both sides of that equation are pushed to their ultimate extremes.) Jake knows that his celebrity and history are worth more than his own work; much of his time is spent answering questions, posing for pictures, feeding his public image in lieu of creating images of his own. Lights flash in his face and cameras are thrust at him; one member of the throng declares, “I’m doing a film and he’s doing a book about Mr. Hannaford,” and Brooks retorts, “And I know somebody somewhere who isn’t.”

Brooks is a much younger filmmaker whose career was launched by Jake, and who has quickly achieved a level of commercial success and even critical acclaim that has long escaped Jake. Brooks is also the world’s leading expert on the subject of Jake Hannaford, whom he interviewed (and tape-recorded) extensively for a book about the elder director, a project that has been abandoned. (The same thing happened with Bogdanovich and Welles; they began their copious set of recorded interviews in 1969, but the book based on the interviews, “This Is Orson Welles,” edited by the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, didn’t come out until 1992.)

In “The Other Side of the Wind,” Welles displays an extraordinary dramatic imagination, in an extended early sequence that, in the hands of other filmmakers, would likely have been a mere throwaway: the trip from the studio, by private bus and public bus, by car and motorcycle, to Zarah’s villa for Jake’s after-work birthday party. There, the characters, their idiosyncrasies, and their relationships are not just established but set in motion. A frenzied agitation begins to build, which, when compressed into the confines of the party, yields ever more intense and resonant clashes—mainly the clashes of the vivid and fierce survivors of old Hollywood who form Jake’s entourage and the younger generation of graspers and strivers, mere pallid and wraith-like imitations who are taking their place in the business and the culture at large.

Grand actors from classic movies play the grand roles of Jake’s cohorts, employees, defenders, and enablers, and each of them is heightened and sharpened and energized (as most actors are) in Welles’s force field. The teeming cast of characters includes the hard-nosed producer who does Jake’s “dirty work” (Paul Stewart); Jake’s film editor and fierce defender (the forceful and incisive Mercedes McCambridge); the tough-talking, hard-drinking production manager (Edmond O'Brien); the fedora-wearing makeup artist who’s Jake’s patsy and insightful fellow-artist (Cameron Mitchell); Jake’s factotum (Norman Foster) who’s also his delegate to a high-handed young studio boss (Geoffrey Land); and a brazen film critic (played by Susan Strasberg) who’s reputedly loosely modelled on Pauline Kael.

Huston and Bogdanovich, especially—had the movie been completed in its time—would have long been celebrated for their performances here. The macho Jake, a hunter and sportsman, is as reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway as he is of Welles himself. Like Hemingway, Jake’s career has a significant international prewar prestige, and his public image is based on his man’s-manhood as well as his art. (For that matter, the date of Jake’s death, July 2nd, is the same as that of Hemingway’s.) As Jake, Huston brings a coruscating, cruel, self-aggrandizing and self-deprecating irony along with the coiled, angry ferocity of a wounded lion. Bogdanovich, dialectically deft and theatrically agile, captures the defensive urgency of an ambitious young professional in a shifting power relationship with his falling idol (and does some droll and dandy imitations of James Cagney and James Stewart in the process).

Just as the soundtrack of “Citizen Kane,” largely influenced by Welles’s work in radio, is as revolutionary as his visual, narrative, and actorly concepts, so “The Other Side of the Wind” has a collage-like soundtrack of rapid-fire dialogue, rich in barbed wit and cynical observations, confessional anguish and strained conflict and lacerating insults. The result is an extraordinarily complex, polyphonic audiovisual experience. The movie’s images, also a kaleidoscopic collage of formats (16mm. and 8 mm., color and black-and-white, as well as the lavish widescreen 35mm. images of the film-within-a-film), play less like the primary mode of experience than like a picture-track that runs parallel to and in counterpoint with the dialogue and sound effects (as well as Michel Legrand’s music, mainly apt but occasionally heavy-handed).

The shots seem like so many aperçus, as if marking the sharp turning of a head at the moment of an ear-catching remark, or like a serendipitous, subliminally guided glance at the person in the room who’s about to make one. (The editing is credited to Welles and Bob Murawski.) The tense and jangling effect of the slipping-back and rushing-ahead of the audiovisual experience is to tangle a viewer in the multiple lines of power, conflict, memory, pain, and desire that crisscross the film and bind the characters bitterly together.

The younger generation of Hollywood is embodied in a varied range of characters, including a scholarly pest (Joseph McBride), a slick directorial rival of Brooks’s (Gregory Sierra), and a naïve high-school senior (Cathy Lucas)—and, especially, in the characters of the two lead actors in the film-within-a-film, the actor John Dale (Robert Random) and the unnamed actress, played by Oja Kodar, Welles’s partner, who co-wrote the film with him. The role of the actress is a strange one: the movie leaves it uncertain whether she is in fact Native American or is merely playing a Native American, in redface, in the film-within-a-film. In any case, the actress doesn’t speak—in the movie, on the set, or at the party. She endures insults (such as “Pocahontas” and “Minnehaha,” as well as a cruel joke at her expense in the presence of the assembled guests). Nonetheless, in her likely seething endurance of insults and her stoic silence, she’s more than a survivor—she’s fashioning her success, which arrives quickly, in the course of the action, and which promises to rapidly propel her far beyond Jake’s deflating orbit.

The centerpiece of the wild party is a screening (interrupted with comedic calamity) of an incomplete rough cut of the film-within-a-film, which is itself both a work of flailing desperation and furious originality. It’s perched delicately on the edge of parody—of Euro-chic art-house eroticism with an intellectualized sheen—while conjuring an authentic psychosexual frenzy of the sort that had always possessed Welles’s work invisibly, that shimmered at the surface of his 1968 film “The Immortal Story,” and that, here—in keeping with the new freedoms of the times—bursts out with a diabolical intensity. It’s suggested that Jake, seeking a new foothold in Hollywood, is trying to make a movie that’s in synch with the new generation of young people, and that his orgiastic, rock-filled, myth-laden drama is the unsuccessful, perhaps even somewhat ludicrous result.

Yet that film-within-a-film is a grand artistic success in its own way. In its confessional frankness, it’s in authentic synch with its times in ways that go far beyond its potential appeal to a studio head; it’s seemingly a self-revealing gush of sexual conflict and torment that’s unlike anything Jake—and Welles—had ever done. Symbolic and abstracted, it is a work of sexual modernism: clean, hard-edged style, highly inflected and distorted compositions, avant-garde architecture, chrome and glass, a fenced-in ghost town, and a Western movie set; borrowings from Godard, Antonioni, and even from Welles himself (in a striking scene of maze-like striated shadows reminiscent of the fun-house-mirror sequence in “The Lady from Shanghai”).

Both the unnamed actress and John Dale are nude for most of the film-within-a-film. But John Dale’s nakedness proves to be utter vulnerability and powerlessness—not least because Jake, whose monumental, aggrandizing filming of the actress displays her self-possession and command, also films her character’s power over the male character, rendering him the passive object of her desire while turning John himself into the target of Jake’s own derisive, wrathful designs.There’s no dialogue in the film-within-a-film, except for the dialogue that Jake himself provides, on the megaphone, shouting orders to his actors, in particular, in the course of a sex scene between John and the woman, in which Jake threatens, endangers, and humiliates John.

That relationship—between Jake and John—is at the core of “The Other Side of the Wind.” It’s something like the Rosebud that is both there and not there throughout the movie. (Several of the party guests allude to Jake’s barely repressed homosexuality.) That relationship torments Jake and threatens the completion of his film; it’s diagnosed (both by Julie, in her critical bravado, and by members of his entourage, in their awed regret) as both a canker and a motive of Jake’s entire career, only the latest in a series of destructive actions toward his actors—his handsome young male actors—that has cast his entire career into chaos. Jake’s resulting sense of loss pervades “The Other Side of the Wind” from beginning to end—a loss that Jake has done everything he could to provoke.

In dialogue of a painful and self-diagnostic frankness, Welles looks at Jake’s fusion of creation and destruction, suffering and cruelty, frustration and wrath. In its dramatization of the great director whose legend has outlived his career, he both reveals his own anguish and unveils his own greatest creation: namely, himself. It’s the role in which he found himself trapped, in a performance as a tragic hero that would, tragically, overwhelm and consume his authentic artistic heroism. And as the decades-long simmer and wrangle over the completion of “The Other Side of the Wind” and the new fervor that, forty years later, it’s stirring up, his creative power remains as forceful in its ghostly ruins as it was in his youth—not least because, from the very start, he understood and anticipated the wreckage of which his life and art would be built.

Sourse: newyorker.com