The trailer for the first season of “BoJack Horseman” is adorned with one of those savant-like Internet comments: “This trailer tricked us into thinking it’s just a dumb funny show when in actuality it’s dark and depressing.” While Netflix technically classifies the show as a comedy, the episodes make you laugh and cry in equal measure, using humor to disarm you before punching you in the gut with tragedy. The show delights with animal puns, absurdist humor, and show-biz jokes—all threaded together by an otherworldly visual style, created by the cartoonist Lisa Hanawalt. It also ventures unflinchingly into those dark and depressing places, with no easy happy endings in sight—a multi-season meditation on what mental illness is, and what it does. Twelve new episodes, already hailed as ever more distressing and meta, arrive on Friday.

“BoJack Horseman” is the love foal of the writer and creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg and Hanawalt, whose comics provided the inspiration for BoJack’s look. Bob-Waksberg, who is thirty-four, is the self-described “son of two professional Jews.” He wears glasses and is balding, and has some beard stubble and a charming gap-toothed smile. His mother and grandmother, Ellen Bob and Shirley Bob, co-owned a Jewish book-and-gift store called Bob & Bob. Hanawalt has dirty blond hair and looks like John Singer Sargent’s “Madame X” in sportswear. She is an artist who started drawing comics at “the age of six or seven.” Their friendship took off in high school, in Palo Alto, when Bob-Waksberg cast Hanawalt in a play he wrote called “The Family Continues,” which Hanawalt describes as “a super-surreal play in which I had to pretend to give birth onstage and stuff.”

“I think we were kind of drawn to each other as like-minded weirdos,” Bob-Waksberg says, adding that the theatre department was “a haven for all these people who didn’t fit in anywhere else, as I think most high-school theatre departments are.” Hanawalt remembers hanging out with Bob-Waksberg in the so-called green room, which was just the drama classroom. “He would look at my sketchbook and make up little stories about the characters, and we would make jokes about, like, what kind of TV shows we’d make, although I don’t think either of us honestly thought we’d be doing that later in life.” Bob-Waksberg’s memory is similar. “I think we had a mutual prep period or something where we both didn’t have to go to class, and we’d just, like, sit in the green room and chat all day. She would doodle stuff and I would, like, make up voices for them, or we’d talk about different cartoon characters we made up. I don’t think either of us assumed we would one day be actually professionally making a cartoon together.”

Bob-Waksberg went to college in New York, while Hanawalt went to art school in Los Angeles. They stayed in touch through LiveJournal, collaborating long distance on a Web comic called “Tip Me Over Pour Me Out,” which was about Bob-Waksberg’s experiences dating in New York. Of art school, Hanawalt says, “I was doing mostly, like, really big, weird, funny paintings, and ceramics and photography. And I kind of didn’t know what I was gonna do when I graduated.” The big, weird, funny paintings were “all really silly,” she says. “A lot of them were, like, just weird juxtapositions of things. Like car crashes and monkeys fighting. There was one that was just a pile of military equipment and tanks surrounded by giant owls.”

She says that some classmates were unsure how to take her work, which was both gruesome and jokey. “I always thought that a lot of the art world takes itself way too seriously. Or, like, a lot of the art world, I feel like they don’t know what to do with funny women. Men can get away with being flippant in a gallery setting in a way that women can’t.” The absurdist grotesquerie of male fine artists such as Paul McCarthy, with his sculptures of gnomes holding butt plugs, springs to mind.

After college, Hanawalt took a job as a secretary in Glendale, coming home at night to draw. The gallery-painter path that she’d envisioned didn’t pan out. “I was, like, ‘I’ll get solo shows in Chelsea, that’s what I’ll do!’ That didn’t happen, so I went back to comics,” she says. She freelanced as an illustrator for publications like Vice, augmenting that income by doing pet portraits that she’d “trade for beer and money.” She met other cartoonists through making comics, and moved from L.A. to Brooklyn to hang out with them more often. “My disposition is that of a cartoonist,” she says. “We’re all kinda, like, funny weirdos who don’t take ourselves very seriously.”

Lisa Hanawalt, whose comics provided the inspiration for BoJack’s look, says she has been obsessed with drawing anthropomorphized animals for as long as she can remember.

Photograph by Ross Mantle

In Brooklyn, she shared a studio with “a bunch of other women cartoonists, and we called it Pizza Island.” Those other cartoonists included Julia Wertz (“Tenements, Towers and Trash: An Unconventional Illustrated History of New York”), Sarah Glidden (“Rolling Blackouts: Dispatches From Turkey, Syria, and Iraq”), Domitille Collardey, Kate Beaton (“Hark! A Vagrant”), and Meredith Gran (“Octopus Pie”), a veritable Who’s Who of hyper-talented women currently working in indie comics and illustration. They met I.R.L., through the local Brooklyn D.I.Y.-comics community, where they had tables at book and zine fairs, and through the Internet, where they read one another’s Web comics.

Hanawalt scraped together rent through freelance illustration work and by selling comics and original art at festivals. When I ask what her professional plan was before “BoJack” appeared in her life, she admits, “I really didn’t have a plan. I guess I find it best not to have a plan, ’cause then I’m not disappointed. I don’t know if that’s the best strategy for most people, but I sort of always assume everything’s going to fail. So I’ve got a Plan B and a Plan C, and I’m always, like, ‘Maybe I’ll just move to the desert and make pots.’ ”

Hanawalt has been obsessed with drawing anthropomorphized animals for as long as she can remember. “I just really have always loved animals. I’ve always been focussed on them. I’m not quite sure where that comes from. That feels like a part of my DNA, honestly,” she says. She has also been obsessed with horses since she was a kid, and rides them whenever she can. When I ask what she loves about horses, she says, “Oh, if only I could answer that question. I don’t know! They’re so intrinsically good. It’s like asking why someone likes ice cream. It makes me feel good to look at them. I wish I didn’t like them because they’re, like, very dangerous and unpredictable. Like, I was riding a horse the other day, and she’s a really solid horse, like, she thinks about things before she reacts. And she saw a bucket, someone had left a bucket where there’s not supposed to be a bucket, and she found that to be terrifying. I had to get off her, because I was, like, I’m gonna fall if I keep trying to ride near this bucket.” She relates to the horse, and describes herself as a “super-anxious person” plagued by personal scary buckets.

Hanawalt discovered indie comics in high school. “I read work by Renée French and Phoebe Gloeckner, and both of them really blew my mind, ’cause I was, like, here are these two women who are being so candid about their lives and their feelings and, like, how disgusting life is. Their comics are really grotesque in different ways, so that was a huge influence on me.” I bring up Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s cover of “Twisted Sisters” No. 1, where a woman sits on the toilet looking into a mirror and expresses self-loathing, as something that opened my eyes to the true possibilities of underground comics. Hanawalt says, “These people are perverts. I love it. I’m also a pervert.”

Hanawalt is fascinated in particular by the ways that sex manifests in the animal kingdom. One of her recurring motifs is snakes with human breasts. “I recently learned that half of snakes lay eggs and half of them give birth. I found that so interesting,” she says. On “BoJack,” the absurdities of animal behavior are strung through a show about the tragic absurdity of human life. “Every once in a while, we’ll try to remind the audience that these are animals. You sort of forget after a while,” she says. The jokes are mostly subtle, like BoJack grabbing a bowl of sugar cubes from craft services, but occasionally something overt happens, such as the cat character Princess Carolyn coughing up a hair ball.

Bob-Waksberg was in a comedy group at Bard called Olde English, which got a manager after graduation. He wrote a spec TV script and, encouraged by the group’s manager, decided to move to Los Angeles to get into television writing. “I would say the beginnings of ‘BoJack’ actually came from when I first moved to L.A. and I was staying in a house that was, like, a friend of a friend’s, up in the Hollywood Hills,” he says. He rented the smallest room. “It was, like, four hundred dollars for this tiny tiny room in this beautiful house that actually looked a lot like BoJack’s does. And I remember looking out over the city and feeling simultaneously on top of the world and also never more isolated or alone.” Bob-Waksberg’s first experience of L.A.’s unforgiving desert of the surreal was the genesis of the BoJack character, whom he describes as “somebody who’s had every opportunity for success but still can’t find a way to be happy.”

Bob-Waksberg did manage to find work as a TV writer in Los Angeles, albeit on “two network sitcoms that both got cancelled after six episodes.” He recalls going out for a job with a very successful sitcom showrunner he deeply admires and, during the interview, saying, “I think the best comedy comes out of sadness.” The showrunner, whose own work has a decidedly optimistic tenor, asked Bob-Waksberg what he meant, “and I realized I didn’t have an answer, ’cause to me it was so obvious, and obviously true” He also realized he was definitely not going to get the job.

Later, a fledgling animation studio that had a deal with an Internet TV network asked Bob-Waksberg if he had any ideas for animated shows, and he said his first thought was, “Can I use this as an excuse to work with Lisa again?” He went to Hanawalt’s Web site, printed out some of drawings, and, as they’d done in high school, made up a narrative to go with the characters that she’d drawn. Here is how Lisa remembers it: “He wrote me an e-mail in, like, 2011. It was titled ‘BoJack the depressed talking horse,’ and he was, like, ‘What do you think of this idea?’ and described it to me. And I was, like, ‘Oh, that sounds cool! Sounds a little depressing. Kind of reminds me of Ben Stiller’s character in “Greenberg.” ’ He was, like, ‘Yeah! That’s exactly what I was thinking, totally an inspiration.’ And I was, like, ‘Yeah, sounds depressing, maybe make something more lighthearted.’ ”

Bob-Waksberg persisted, and returned to Hanawalt six months later. “At each step I was sort of hesitant to get involved,” Hanawalt says, “because I am very commitment-phobic about collaborating on giant projects. ’Cause I was, like, ‘Oh, I’m doing my own thing, that’s cool.’ But eventually I got convinced to design the main characters. And then they made a pilot episode that I art-directed. And then just sort of slowly it came together, and I never expected it to become a show, much less a show with this many seasons and, like, a fan base. And in 2014 I moved back to L.A., to work on it full time, and, yeah, it’s been really great and really exciting.”

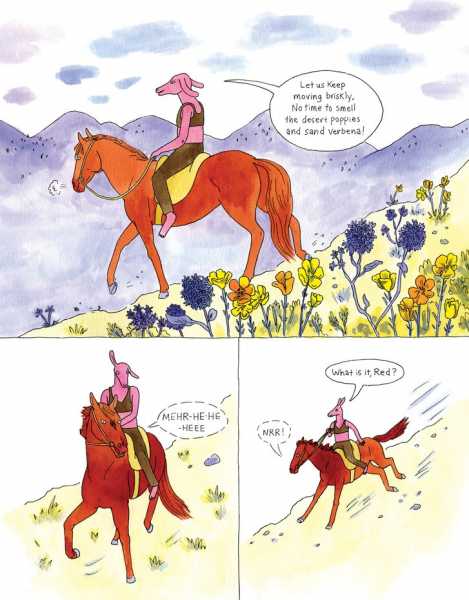

Hanawalt has also just released her third book, a graphic novel, “Coyote Doggirl.” Inspired by classic Westerns like “The Searchers,” Hanawalt puts her own weirdo bent on the genre. The titular character is a pink coyote who rides a horse through an endless Western landscape on a quest for revenge, encountering a tribe of wolves whom she bonds with and then heading back out alone to fight some bad dogs who are out to get her. Painted with watercolors that emphasize the vivid natural beauty of landscapes others might see as desolate, the book is about the tug between self-reliance and community. It’s an introvert’s paean to the pleasures of being alone. It’s also a love-letter deconstruction of the modern Cormac McCarthy-inspired Westerns that still place a premium on machismo and male violence.

Hanawalt recently released her third book, “Coyote Doggirl,” about a pink coyote who rides through an endless Western landscape on a quest for revenge.

Illustration by Lisa Hanawalt. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.

Hanawalt is a female pioneer in the field of animation, which has been a boys’ club since the days when Disney refused to hire women as animators. Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim famously never had any female showrunners; women only broke through earlier this year, when the network bought a show from the very established Amy Poehler. Rebecca Sugar, a veteran of the beloved weirdo animated show “Adventure Time,” became the first female show creator in Cartoon Network’s history, with the award-nominated “Steven Universe,” which is now one of its most popular series.

Hanawalt was able to develop her voice as an artist outside of animation before joining “BoJack,” and Bob-Waksberg’s faith in her led to her designing the entire look of an animated show. Having gained confidence from “BoJack,” Hanawalt is now the showrunner of her own series, another Netflix original cartoon, “Tuca and Bertie,” which is about a friendship between two female birds, voiced by Tiffany Haddish and Ali Wong. Bob-Waksberg is executive-producing “Tuca and Bertie,” although Hanawalt describes his job as “Lisa whisperer.”

Both Bob-Waksberg and Hanawalt describe “Tuca and Bertie” as a different beast from “BoJack.” There is only one writer from “BoJack” on “Tuca,” and Hanawalt is writing the show, something that she never did on “BoJack.” Bob-Waksberg convinced Hanawalt that the comics she had written qualified her to write a TV show. They credit their studio with surrounding Hanawalt with people who can help her realize her vision. She says, “I learn that constantly, that you don’t really have to be good at something before you do it. You kind of just have to do it, and then you learn on the job.” Bob-Waksberg cracks, “Welcome to the secret that every man inherently understands.” Lisa laughs and responds, “And women don’t somehow . . . but also, people don’t believe in them.” The two have been in their Hollywood office constantly, working on both shows simultaneously.

Hanawalt has been drawing her Tuca the toucan character for a while. “I created her after watching a nature documentary about toucans where they were, like, poking their beaks into other birds’ nests to steal the eggs and gobble them. So the birds were creating these nests that were longer and longer, in order to avoid the toucans stealing their young, basically. And I thought that was so funny. Like, toucans are so selfish and greedy, I really related to it. They’re so naughty. It’s so funny to me.” Hanawalt is doubting herself about her new role, but Bob-Waksberg reassures her she’s capable. “You’re doing a great job. But welcome to the life of a writer, constantly thinking you suck!”

Sourse: newyorker.com