On the 25th of October, 2002, the Lebanese artist Fouad Elkoury wrote an e-mail to a woman he’d never met:

Thursday, 10h30, getting ready to get on the plane (I hate leaving), the concierge puts your letter at the entrance to my room.

Thursday, 15h30, once in the air I open the envelope and discover your letter with amazement. Stuck between two other passengers, it’s impossible for me to express my reaction.

Friday, 13h30, in Beirut, after having been to the corner barber to get my hair cut to conform with the local style, I respond to you: yes.

Fouad.

The author of the letter he’d opened on the plane, in the middle seat, was Isabelle Mège, a medical secretary at the Hospital Saint-Antoine, in the Twelfth Arrondissement of Paris. She had seen Elkoury’s exhibition of black-and-white documentary photographs “Sombres,” from 2002, at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, and in her letter she proposed working with him on the creation of an image in which she would be present. What kind of image would be up to Elkoury. At the time, Mège was thirty-six, and for sixteen years had been contacting photographers whose work she had seen and admired, asking them to incorporate her somehow into their art. She had, by then, a large collection of images by working artists. Not all could be called portraits, and they varied in their style, but they all depicted her body, even if it was a tiny or unrecognizable part of it. In making the first contact with artists, she often used some version of the phrase “J’aimerais m’apercevoir à travers votre regard,” or, “I would like to see myself from your point of view.”

In May of this year, in his living room in the Marais, the same room in which, in 2003, he had taken the photograph of Mège, Elkoury said that he had been surprised I had contacted him with a specific interest in that one image, which he has never exhibited or spoken about. It’s a dramatic, shadowy black-and-white portrait, in which Mège, dressed in black, sits in a chair, staring at the camera above her. He had agreed to her request because, he said, “I could tell this project came from an obsessive mind, this strange project of being photographed by photographers she liked—not those she thought were famous, but those she liked.” When they eventually met, he had been taken aback. “She was very ordinary, a very normal-seeming person. I had thought, based on her letter, that she might be unusual.”

The image by Fouad Elkoury taken at his studio in the Marais, Paris, in 2003.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FOUAD ELKOURY

Mège began her project in 1986, when she was twenty years old. She had just moved to Paris from the province of Auvergne, not far from Lyon, where her father was the manager of an automobile-equipment shop and her mother stayed home. When asked about her childhood and adolescence, she uses words like “fine” and “calm” and “French.” At the time she came to Paris, she had never met an artist, and had been to few museum shows, but she collected record covers and postcards of images that appealed to her. One Saturday in mid-July, she went alone to an exhibition by the portrait photographer Jeanloup Sieff at the Musée d’Art Moderne. Stunned by the images, which depicted anonymous and ordinary, as well as famous, subjects, she wrote to Sieff, telling him that she liked his work. To her surprise, he telephoned her a few days later. She wrote in her diary, which she kept from 1986 until 2008, “He calls me, I’m extremely moved, surprised, I feel drunk.” She asked him if he would consider making a picture of her.

After working together at his studio for an hour or so, Sieff announced that there had been no film in the camera—he had been testing her. She was taken aback, but the session had taught her something; she left with the feeling that she had been, up until that point, “without photography, and without a photographic past,” as she wrote in her diary. She began looking at photography books, buying magazines, and keeping track of the names in the exhibitions she visited. Methodically, and recording her activities in brief, elliptical diary entries, she sought out other artists, explaining how she had encountered their work and asking to be used in it. Months later, after seeing her work with other photographers, Sieff asked her back to his studio and finally made an image with her.

By 1990, Mège’s collection had grown to around sixty images—most of them black-and-white, and almost all nude, as she preferred to be photographed. With savings from the secretarial job she found at the hospital, she had travelled to Liège, Amsterdam, Lausanne, Basel, Barcelona, Prague, and Caracas to meet with artists. In Clichés, a photo magazine, she saw images by Joel-Peter Witkin, an American photographer in New Mexico who makes deeply researched and pictorially inflected still-lifes and tableaux of grotesquerie, and who has described his work as something like “the last thing a person sees or remembers before death.” The images that he made around the time Mège discovered his work include a woman posing with a freshly slaughtered horse carcass and a man being fisted up to the bicep by someone just out of the frame. At the Pompidou Centre, she looked for monographs and books of his photographs.

Over several months, Mège wrote three letters to Witkin, first through his Paris gallery, Galerie Baudoin Lebon, and then to him directly. She received no response. For her fourth overture, she changed course, asking a nurse colleague at the hospital to draw some blood from her arm, and to divide it up into three vials. She attached these to a new handwritten note, which she sent in the post to Albuquerque, without telling her colleague what the blood was for or declaring the contents to the postal service.

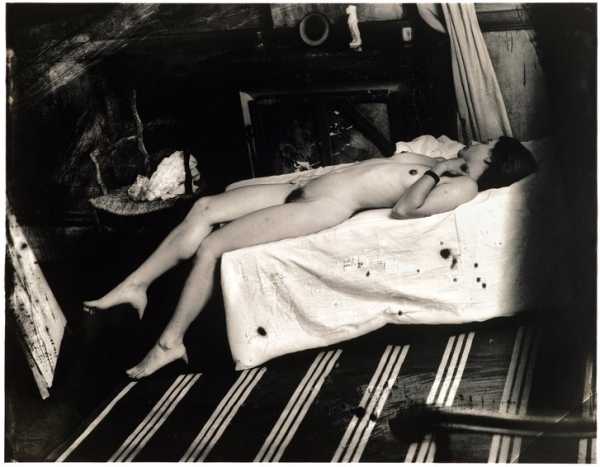

“There were twenty or forty stamps on the package,” Witkin told me recently. “I wasn’t expecting the blood. But that was a gesture that I understood.” He agreed to meet her two months later, the next time he was in Paris. After meeting at Lebon’s gallery and seeing some of her images, Witkin went away and, as he always does before he shoots, sketched an image: the prototype of what would become one of his best-known works, “Nègre’s Fetishist.” An homage to the earliest photography and to human perversion, the photograph is a direct reference to a negative in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay that Charles Nègre, a painter who became one of the first professional artistic photographers, made of his lover. In Witkin’s image, Mège is lying supine on a daybed that is spattered in a dark substance; it might be ink, or ash, or blood. Her face is turned from the camera, toward what looks like a stove. There is something diabolic in the sooty image; it takes a moment to notice the tiny, fleshlike, pointed polyurethane heels at the end of her tensed feet, which give Mège an otherworldly, succubus-like aspect. Her body looks ordinary, and also possessed; something nightmarish has just happened, or is about to.

“In her body, there was a desire to make the image,” Witkin told me. “The photograph needs the sitter. And that is one of the best images I have ever made. I could not have made it with another person.” Mège remembers having “done the impossible, entered the world of Witkin.” In 1995, five years after the creation of “Nègre’s Fetishist,” there’s a note in her diary about the photographer. At a dinner party thrown by the filmmaker Jérôme de Missolz, who made documentaries about both Mège and Witkin in the nineteen-nineties, Witkin turned to her and lowered his voice. “Will you write me a note that promises me your body, after you die, so I can photograph it?”

“No,” Mège said. “I intend to outlive you.”

“Nègre’s Fetishist,” a image from 1990 by Joel-Peter Witkin, whom Mège pursued for years before he agreed to work with her.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JOEL-PETER WITKIN

After each shoot, Mège would follow up and ask the artist for a print, signed and sometimes numbered by its edition. The print would go into her archive, along with any artifacts related to its making; Elkoury’s letter, for instance, is accompanied in the archive by Mège’s notes about their encounter (he was late to their first meeting, and arrived with his shoelaces untied). Also in her archive are the heels that Witkin attached to her feet during the 1990 shoot, and a news item about Japanese customs having seized incoming copies of the magazine ARTnews to prohibit their circulation; the photograph, in which Mège’s pubic hair is visible, was considered obscene. Her diarizing and collection of correspondence, clippings, image reproductions, and relevant items reveal that the planning around certain images often lasted years. Several times, having worked with an artist to make an image, she was unhappy with the results and excluded it from her collection. When approached by artists who wanted to work with her but for whose work she had no feeling, she refused.

Mège felt strongly that no money should be exchanged in these interactions. (“As soon as there’s a question of payment, it’s dead, you fall asleep,” she told me.) She also asked each artist to sign a contract printed on a three-inch slip of paper, stating that she would have the right to exhibit or publish the image for noncommercial reasons only. In 2008, by the time she was forty-two, she had around three hundred images, and she began to feel that the project was complete; she took to calling a hundred and thirty-five of the images “the collection.”

“Mège’s collection is very coherent,” Henri Foucault, who was one of the last artists who worked with her, in 2008, and who saw a selection of the images, told me. “She didn’t work with just anyone.” Several photographers told me that they had expected someone to come asking about Mège, eventually. “Right now, no one outside really knows about her. But I think, as time passes, we will hear more.”

It can be tempting to compare Mège to other people who have inhabited the word “muse,” but the noun doesn’t quite fit her. Several of the artists who photographed Mège also participated in another project, coördinated by the actor Isabelle Huppert, who in 2005 produced an exhibition and a book of portraits of herself—smoking, at the bar, in costume, nude—by artists including Sieff, Robert Frank, and Henri Cartier-Bresson, many of which fit comfortably into the genre of celebrity portrait. “Huppert is the perfect counterexample to what Mège has done,” Foucault said, because “you can’t make it an artistic endeavor if you’re a professional model. There are artists who never got past the fact that they were photographing an actress, Isabelle Huppert.”

Jean-Luc Moulène photographed Mège in 2003. He said, "exactly what she's made we don't quite know . . . and it's impressive."

PHOTOGRAPH BY JEAN-LUC MOULÈNE

Jean-Claude Bélégou, who photographed Mège in 2003, and whose color photographs often explore the relationship between the artist and model, wrote to me that Mège was working at the same time that young female photographers were turning to the form of autoportrait. He compared her to artists who use their own bodies in their work—Sophie Calle, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman. Calle, a writer and conceptual photographer, also documented her meetings with strangers—as in her book “Suite Vénitienne,” from 1983, a diary of twelve days following a man named Henri B., and “Exquisite Pain,” the diary of a breakup. When I asked Mège about the idea of self-portraiture, though, she told me that it would not have fulfilled her; the exhilaration was in entering, over and over again, the artist’s universe and the working process. Like many of those she worked with, she was attracted to photography because it necessitates an interaction with the world, no matter how minute.

In an e-mail to me, the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, who has written about art and its intersection with philosophy, told me that the key to understanding Mège’s work is “the act itself . . . an act that makes her into an artist of some sort.” He was interested in the fact that, while Mège appears to have the will of an artist, she distributes the means of creation to others; she is an artist whose medium is other artists. He invented new words to describe her work: “It’s a selfothermade,” he wrote, “not an auto-portrait . . . but it’s not a simple alloportrait either.”

Gilles Cruypenynck took Mège’s photograph in 1987, having met her by chance. “I was very late at the Pompidou library, and so was she,” he told me. “A twenty-year-old girl who makes images of herself—that can be very banal. At the start, I didn’t understand the magnitude. I came to understand, eventually.”

Mège’s collection, kept in archival boxes in a study in her home, has been seen in its entirety by fewer than five people. Those who are aware of it belong to the community of artists, curators, and scholars who formed around it. Cruypenynck wrote to me that, in retrospect, what became important to him over time was “the particular feeling of being connected to a galaxy of artists who had this same, singular relation to Isabelle.” The idea of community had been particularly important in the world of photography, he suggested, which three decades ago “was much less popular, much less noted than it is now.”

Jean-Claude Lemagny, an honorary curator at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, where he worked from 1968 to 1996, said of Mège, “She knew about every contemporary photographer there was. That was very clear. It’s also clear in her choice. There were names in there even I didn’t know.” In 1995, after seeing images from photographers who Mège had worked with, he asked to see her collection. “I remember she had them in very fine archival boxes. I recognized them immediately, and knew exactly how much they would cost. It struck me, because she never had any money at all.” He asked Mège to donate her collection to the library, where he would exhibit it. She refused; the collection could not be exhibited or acquired, she said, because it was unfinished. Being an artist, Lemagny told me, means “working alone, just like Isabelle did,” for extended periods of time. “With others, but alone.”

Jean-Luc Moulène, who photographed Mège in 2003, said that, “Yes, she has made a collection, but that is academic language, an academic term.” The artists, he explained, “don’t quite know what she’s done. She posed—yes, she posed for me. But exactly what she’s made we don’t quite know . . . and it’s impressive.”

If she had wanted to make her project for the public, Moulène noted, she would have given it some kind of name. “The term ‘artist’ is a way of socializing practice, the thing you do,” he said. “Isabelle is an artist, even if she doesn’t want to be called one. Why would she want to be called that?” If she accepted that term, Moulène explained, her life would change.

In 1991, while working at Saint-Antoine hospital as a medical secretary, Mège noticed a young medical student, an Iranian man named Ali Bozorg Grayeli. She looked into his file in the hospital’s administrative department, found his home address, and wrote him a letter asking if he might see her after work. In 2004, they were married, just before the birth of their daughter, Albane, and in 2012, four years after the birth of their second child, they left Paris for a small village outside of Dijon. Bozorg Grayeli worked as a research professor and practitioner of medicine in the area of the ear, nose, and throat at the university hospital of Dijon, and Mège left her job to take care of their children. Today, Mège and Bozorg Grayeli (she took his name after they married) live together on a tranquil block of land in the small village of Arc-sur-Tille, in a large, modern house, the interior of which has the restrained order of the beginning of a Michael Haneke film.

At fifty years old, Mège has gathers of lines around her eyes, and an observant manner. She was dressed in the most unremarkable way possible, in jeans and a cotton cardigan, and her hair, which was the same mid-back length I had seen in reproductions of some of the portraits of her, was tied back, with barely perceptible streaks of light gray. She speaks quietly and directly, and pauses before answering questions, using no fillers in her speech. When I first arrived, some of my attempts at small talk and joking conversation fell flat when she asked me to repeat myself, or to specify exactly what I meant.

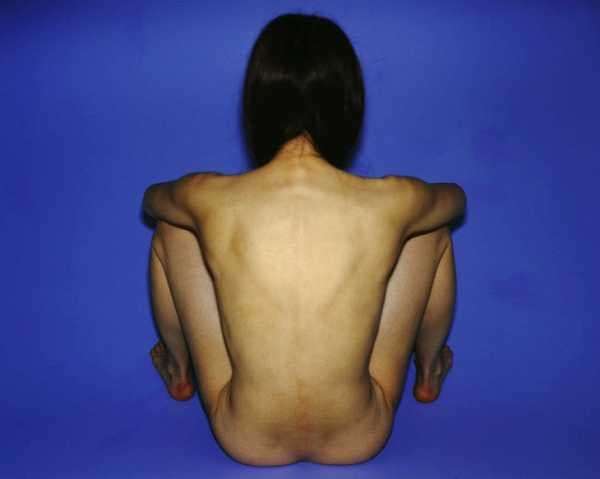

To show me the collection, she put on reading glasses and took the images out of storage, placing them two at a time on a glass-top table in the open light of her living room—not in the order in which they were taken but in the order in which she likes the images to appear. It’s hard not to look for narratives within the collection, but most of the images have nothing to do with each other. Rossella Bellusci’s 1989 photo looks like a pure white square, until the outline of a jaw line and eyes become visible. Frederick E. Bertin’s 1999 diptych resembles a nineteenth-century daguerreotype. Jean-Luc Moulène’s 2003 image, of Mège sitting with her back to the camera in front of a blue background, is cold and semi-abstract; in the collection’s series, it is followed by a succession of cinematic, black-and-white images by Tomio Seike, of Mège in a bedroom-like interior, some part of her body or face always obscured. Next, an unforgiving, flash-lit closeup of her face, from 1997, by Philippe Bazin. Most notable is the way that Mège gave up her own identity to each photograph.

16

A portrait from 1991 taken by the German photographer Martin Rosswog, near Mège's home in Paris.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARTIN ROSSWOG

Looking at images of Mège, I came to recognize her way of removing any deliberate information from her face, and the lithe strength of her legs, their particular proportion to her torso. There are physical tics—a pattern of musculature in her calves, a distinct rough strength in her hands and feet. Though, in each case, the photographer was the director of the image—the one who conceptualized and oversaw it—it was Mège who created it, using her body. Mège has never made an art object—but neither does a dancer, who makes art by moving around from place to place, under the direction of choreographers. If some have trouble coming to terms with what Mège has made or done, it could be useful to think of her work, as conceptual as it might be, as a dance that lasted twenty-two years.

Baudoin Lebon, the gallerist for a handful of Mège’s artists, said, “Some people want a portrait of themselves, at some point in their life. This is not the same thing at all.” One of the images is a closeup of her underarm, another a study of the back of her head. “With Isabelle, she’s not always showing herself,” he said. And yet, Lebon went on, the idea behind the work “is narcissistic. If they were mediocre photos, the whole thing would look terrible. But they happen to be brilliant.” I asked Lemagny about its narcissism, but that was an idea he seemed to become impatient with. If the work is narcissistic, he told me, it is “transposed into work. It’s not a work of psychology. It’s a work of photography. She became a form, a plastic subject.”

Arnaud Claass, an artist who also teaches art history at l’École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie, in Arles, talked in similar terms. “It is definitely a project of narcissism, and I do not use that word in a moral or pathological way. Some people have to explore that side of themselves more than others.” Claass, who photographed Mège in 1996, said, “She was actually working. It was very existential from her part.” While she presented what she was doing as a kind of project, he said, the reality is that it was closer to her vocation.

Mège shrugged when I asked her about the high proportion of male artists in her collection. “At that time, most artists were men. That was whose work I saw.” Then I asked another question, one that had played in my mind since I first learned about the collection. Did the interest of her photographers in the sensuality of her body ever extend into real life? She counted. There were two artists she had slept with. I silently calculated this number, over the twenty-two years that she worked, to be around one per cent of the artists she had worked with. “In life, this sometimes happens,” she said.

Lionel Fourneaux, who photographed Mège before his work became more “mature” and “concentrated,” told me, “The Isabelle images don’t really fit into my work today. She was neutral. Maybe even too neutral for me.” I pressed him on the neutrality of her body, and his voice lifted, in the manner of a person making a potentially surprising counterpoint. “Actually, the particular thing was, she wasn’t trying to sleep with me. She was just so serious about making the photo, the possibility didn’t even enter our dialogue. She completely de-eroticized the situation. I don’t remember how, but I remember that about it. I slept with a lot of models, but not with her.”

When I asked Mège which images were missing from her collection, she named the Australian photographer Bill Henson, whom she began pursuing in the nineteen-eighties, though he ultimately refused to work with her. Henson later told me, about the obsessiveness of her approach, “I would go to Paris, but I never told her when I was coming. I would check into the hotel, any hotel, and there would be a message waiting for me from her when I got there”—asking again if he had reconsidered.

There are certain artists whom Mège has been asking for years for her print, like Patrick Faigenbaum, a portraitist who works like a studio painter. Faigenbaum photographed Mège in 2004, but has never given her the image. She first got to see it when he exhibited it in a show in 2005 at the Galerie de France. His refusal is purposeful. “I did not want my image to become part of her collection at the time, and this was important to me,” he told me. “I did not want it to be there with all the others, because there are artists in there whom she chose to work with whom I do not appreciate at all. Some, but not all. It’s her collection, not mine.” But, he said, “I wanted to make the image with her.” In a café near his studio, he reached under the table and pulled out a book of his work, opening it to a page bearing a realist portrait, perfectly composed and executed, of Mège clothed and seated. “She isn’t posing. It’s not to please or to seduce.” “What’s important to me is to make a photo with him,” she had written in her diary on April 29, 2001, after meeting him to discuss working together.

Faigenbaum’s refusal is canny, in a sense. Often, when I asked certain other artists to explain to me how the image they made with Mège sat within their work, they would go quiet, before admitting that the image had no place in their oeuvre. Henri Foucault—whose characteristic black-and-white photograms of body parts have little in common with the harsh, clinical-looking image he made of Mège’s pregnant body—told me that “she was very insistent. Very, very insistent, very regularly. I had never accepted another model in the way that I did her.” He went on, “The image is not integrated in my usual work. It’s apart. And I always, always pay the models. . . . Really, it would have been much easier for me just to make an image with a model that I’d paid.”

In 1996, the filmmaker Jérôme de Missolz, who died earlier this year, made a short art film about Mège’s work. “I (comme Isabelle)” is a twelve-and-a-half-minute arrangement in which a selection of her images, each illuminated by a spotlight, appear to the viewer in the order in which they were taken. The film, Mège’s husband told me, as we sat in his study in Arc-sur-Tille on a Saturday afternoon, helped him to understand what his wife did as a discipline. For years after they had met, he said, “I was not at all comfortable with it. I just didn’t understand why someone would willingly place themselves in front of the camera. Why isn’t she just a photographer?” He had thought it was a hobby, he said, and he had reservations about immodesty.

Bozorg Grayeli still shies away from particular images. He brought up a 1990 photograph by Seymour Jacobs in which, leaning into blackness, Mège’s white body is reclined, her legs raised, the upper part of the back of her thigh and a creep of black pubic hair the closest thing to the lens. The other focal point of the image, the triangle of her dark mouth and eyes, is set in the resigned, not-quite-bored expression of a young Balthus model. “I see the force of the image, the sensuality in it,” he said. “I understand that it’s deliberate. But I’m not at ease with it.”

Bozorg Grayeli was born Ali, in Iran, but changed his name to Alexis when he received French nationality in 1995, at Isabelle’s suggestion, to make life in France easier. As a medical student and intern, Bozorg Grayeli didn’t always earn money; Mège sometimes supported them both on her secretary’s salary. She convinced him not to leave research for an easier but less stimulating position in private practice when he suffered from the competitive pressure in his field. “I owe Isabelle more than half of my career,” he told me. “She is extremely disciplined. Very honestly, I have students at doctoral and post-doctoral level who lack Isabelle’s mental determination and discipline, who don’t put the energy into their work that she does.” He was uncertain whether he had enough time and energy for children, so she made the decision for him, when she was thirty-nine years old. (“Albane was a surprise for her father,” she said.) In the same way that many of Mège’s artists were initially unaware of the scale and nature of the project in which they were participating, Bozorg Grayeli only realized in retrospect that she had been the silent architect of his adult life. From somewhere outside his ordered study, I got the impression that her understanding may have predated his.

From a 2000 series titled "Isabelle," by Leo Divendal.

PHOTOGRAPH BY LEO DIVENDAL

In 2008, in the final pages of her diary, Mège tried to answer, perhaps for the benefit of any future readers, why she chose to pursue photography in the way that she did, writing about “strong emotion in front of the camera” and photography’s power to “freeze time.” The question of why she wanted to become an image-maker in the first place had seemed too large and too obvious for me to ask during the first days that I spent with her in her home. Not wanting to put too much weight on the question, I waited until she was distracted, and then asked casually if she considered herself an artist, but she admitted only to creative impulses. “No,” she said. “I just wanted to make photos. It was audacious—really, I was just a person who responded to a feeling I had. Others were willing to follow it, too.”

It was the middle of the day, and her family was home, gathering for lunch. She moved around the kitchen that overlooks the ordered garden and pool house, washing salad, setting cutlery on the table. Standing with her in her kitchen as she moved back and forth, the brief lines of her legs, her narrow hips, straight back and small jaw were, for the first time, not abstracted for me into an image. I looked at her strong, bone-filled hands as she dressed salads and pulled a bread knife back and forth, and for a while I enjoyed watching the strange coherence of a human body in motion.

Sourse: newyorker.com